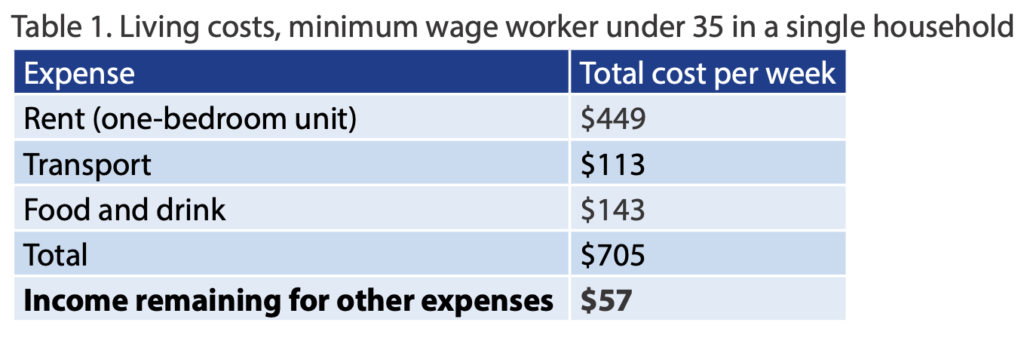

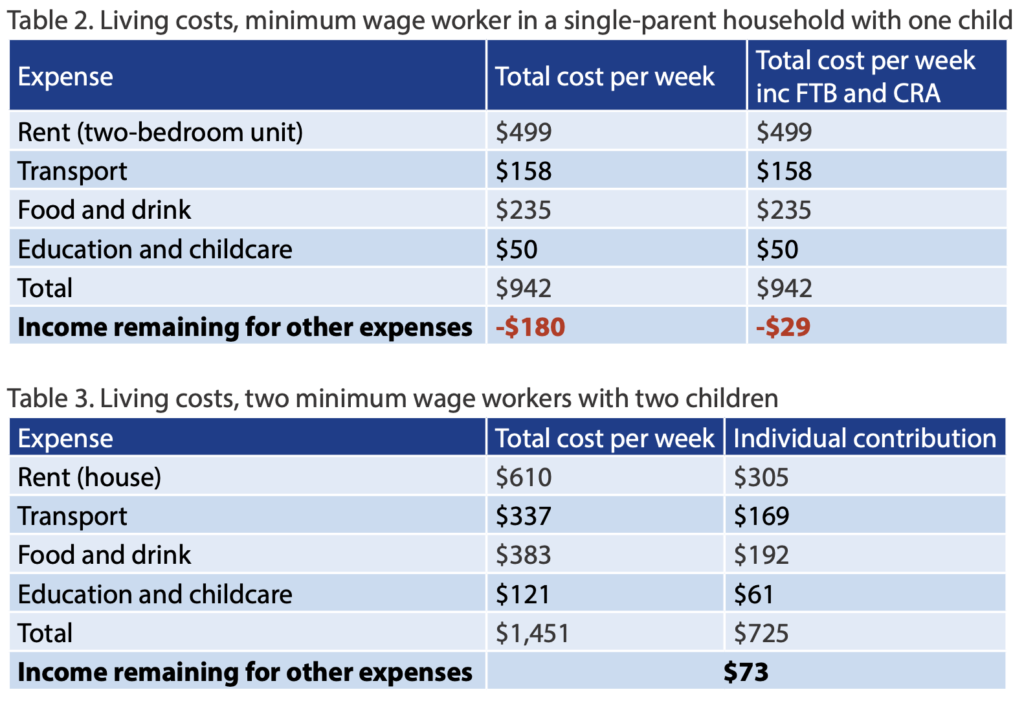

After paying rent, for food, drink and transport, a full-time minimum wage worker has just $57 per week left. according to Anglicare Australia’s Living Costs Index released today. A family of four, with two full-time minimum wage workers, has just $73 left.

The plight of a single parent living alone is worse, with minus $180 per week.

“These numbers confirm what Australians already know. Living costs are spiralling. Essentials like food and transport are shooting up, and housing is more expensive than ever,” said Anglicare Australia Executive Director Kasy Chambers.

“Rents have gone up by 30 per cent since 2020, and they are forecast to keep going up over the next year.

“It is no wonder that record numbers of people are taking up second jobs. People on the lowest incomes, even those working full-time, are being priced out of their own communities.

“Without action, the cost-of-living crisis could force huge numbers of people to turn to agencies like ours for basics – like food, rent, or medicine for themselves and their children.”

The figures calculated by Anglicare do not include monthly and quarterly bills such as telecommunications and utilities, as well as incidental household expenses.

The Anglicare report states ‘A minimum wage worker in a single-parent household would not be able to cover even basic expenses without working extra hours, working late nights or weekends, and relying on additional government benefits. However, even with Family Tax Benefit (FTB )and the highest rate of Commonwealth Rent Assistance (CRA), these households would still fall behind.”

Families and individuals have already begun to seek help in greater numbers. “In late 2022, all Anglicare Australia emergency relief providers reported an increase in demand for services, ranging from 10 percent to 50 percent compared to the beginning of the year. Many reported that they were seeing new clients who had never used their service before, and that many of these new clients were from households with paid employment.”

Even before the increases due midyear in energy bills, energu is a major point of stress. “By the end of 2021, nearly a quarter of a million Australian households were experiencing energy debt and the average debt each household was facing was $1,000.7 In 2021-22 customers with an energy debt of upwards of $2,500 older than 24 months grew by 39 percent.”

Rent is the main stress. “Our findings show that rents are severely unaffordable for minimum wage workers, comprising the single biggest living cost for each of the three households we modelled. In considering these results, it is important to remember that rents continue to rise at prodigious rates. Over the past three years typical unit rents across the country have gone from $372 per week in March 2020, before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, to $496 at the time of the release of this Index, an increase of over 30 percent.10

“For ten years, Anglicare Australia’s Rental Affordability Snapshot has shown that renting a home in the private rental market in Australia is completely unaffordable for people on government incomes,11 and that it continues to get worse. The average weekly rent has risen by nearly 20 percent in the past year.12 The current vacancy rate in the rental market sits under two percent nationally, leaving low-income renters to compete with hundreds of other potential tenants for very few properties.

“Based on the internationally accepted benchmark that rent needs to be no more than 30 percent of a household budget to be affordable for people on low incomes, each of the households we modelled is likely to be under stress, most severely in the case of single-parent households. These results reinforce concerns that minimum wage workers are being priced out of housing. Our Rental Affordability Snapshot found that less than one percent of advertised rentals are affordable for a person on the full- time minimum wage. That is a record-low result, and the first time in the history of the Snapshot that a person on the minimum wage could afford less than one percent of listings.”

In a strongly worded conclusion, Anglicare states, “It has become clear over the past year that many Australians are living too precariously to cope with the shocks brought on by rising living costs. It is critical that Governments understand this as the underlying problem and take action to reduce housing costs and tackle rising rates of poverty… Australians on low incomes did not create this crisis. They should not be asked to bear the brunt. Our goal should be to ensure those on the lowest incomes can weather this storm and that the economy that emerges is more fair and more equal, not less.

Anglicare’s proposed solutions

• Emergency payments of up to $1,000 for low-income households participating in hardship programs with high energy debts

• Community energy programs that support and advice to low-income households on energy and financial hardship.

• A long-term program to grow the supply of social and affordable housing by 25,000 dwellings each year

• Working with states and territories to strengthen rental laws and protect people from unfair evictions and rent increases

• Incrementally reducing the capital gains tax discount over the next ten years. This incremental approach would guard against concerns about the impact of the reform on housing markets

• Using negative gearing to target investment in social and affordable housing. The current negative gearing arrangements, which are not delivering, should be phased out for new investors in the private market.