Rory Stewart, UK Conservative MP turned podcaster who experienced two referenda in Britain, was asked about his experience of Brexit and the Scottish Independence polls by Phillip Adams on Late Night Live this week.

Stewart, the co-host of “The Rest is Politics,” gave an answer that portends a bleak future for referenda. Any referendum.

“I think the first thing that you learned is referenda that are incredibly unpredictable in the modern world, that social media can change people’s opinion in a matter of days very, very quickly. So between the time you call the referendum, and the time that the actual vote happens, so much can change.

“When the Brexit referendum was called, the remain vote was comfortably leading against the Brexit vote.

“I think the second thing that you learn is that any referendum associated with the establishment is going to be in trouble because people like to kick the establishment: kick what they perceive as the elites. So the public sees referenda often is a way of rebelling against anything suggested to them by the government. So it’s very dangerous for the government to think that they’re going to be able to go into this and win over and convince people to change things.

“And I think the third thing is that when people are uncertain, the tendency is normally to say ‘no.

“And I think there’s an interesting connection, isn’t there, between the voice referendum and others. It’s partly about the way in which populist political rhetoric works, the way in which it’s so easy to divide people, that it’s so easy to stoke up fears of different sorts.

“It is so easy to generate a real sort of hysteria about what might be quite a minor measure. I mean, the Voice referendum was not exactly on the scale of full Scottish independence or Britain leaving the European Union. It’s something that you would’ve thought Australia could incorporate relatively easily in its constitutional system. But what happens is that even what I suppose in global terms feel like relatively small decisions when you put [them] to a referendum are exaggerated. So they seem like matters of life and death.”

Rory Stewart’s points have been made by some local commentators, but it was striking to see the problem with referenda crossing national boundaries.

Problem 2

A second reason is what we might call the “Hillary Clinton effect,” a campaign that

• Thought it was going to win and was taken by surprise,

• had too many gaffes, the equivalent of Hillary’s “deplorables” moment: suggestions “No”‘” voters were racist’, and the imbroglio over the number of pages in the Uluru Statement.

• The best campaigners, Senator Jacinta Price and Warren Mundine, were on the other side. Minister Linda Burney and Senator Merride McCarthy were rendered largely invisible.

• The Other Cheek attended a public meeting for the yes case, in which the panellists spent the evening saying how progressive they were – one wanted to speak about her pride in campaigning for Palestine. None of them seemed to realise they needed to win over people more conservative than they. It may be that this “circling the wagons” may have been in response to the unspoken feeling they were losing.

• The Yes campaign did traditional politics, while the No campaign harnessed social media, some of it making the same points as the coalition campaigners, but other outlets sprouted conspiracy theories that were not effectively rebutted.

Why ‘Yes’ should have won

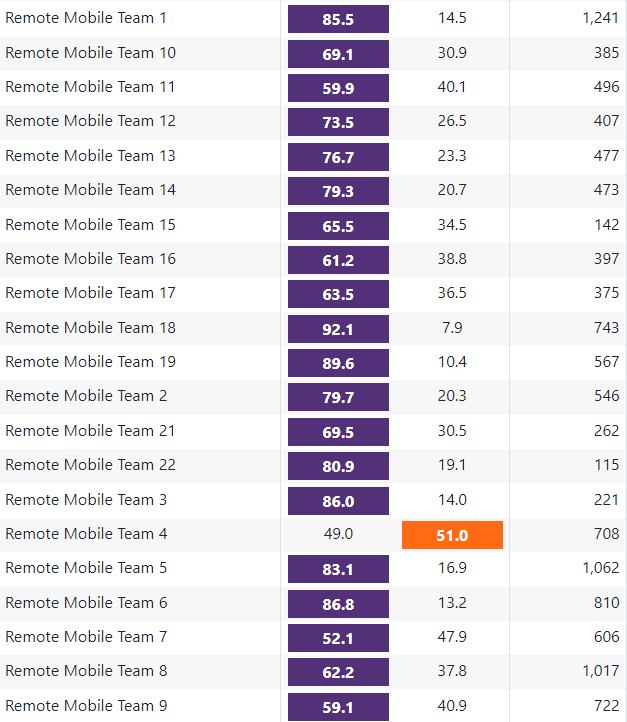

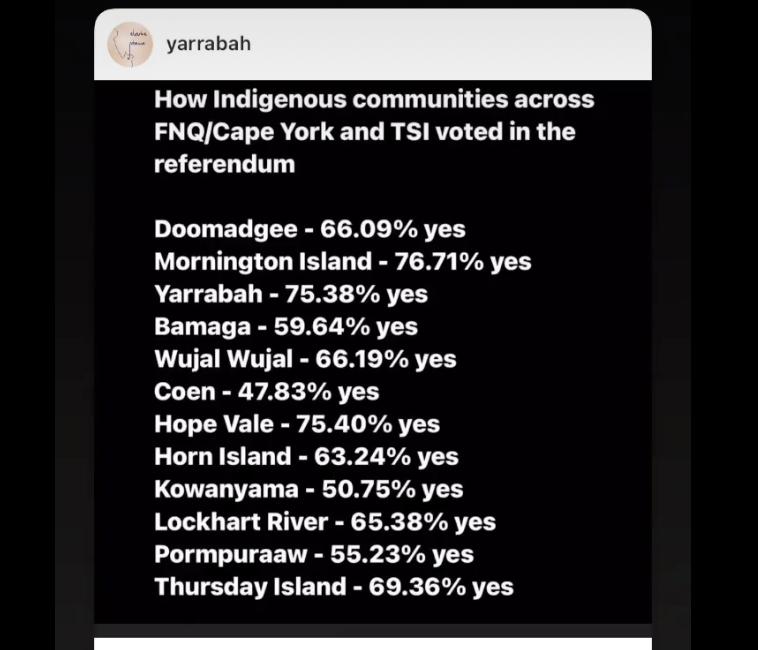

It has become clear that the majority of indigenous people wanted a Voice, certainly those from remote settlements in the Northern Territory. Via Antony Green here are figures from the AEC teams that visited remote settlements. Below that is a table of results from far north Queensland.

The Voice was a modest request, deliberately modest, scaled to be so small, out of regard and love for the wider Australian community. We refused what the First Nation’s people asked for, even though it was so little.

Thanks John. I appreciate your coverage.

As someone who lives in outer suburban Melbourne, from what I saw a lot of people were concerned that it wasn’t ‘so little’.

It was presented as such, but by failing to provide even draft legislation of what it could look like meant that people doubted that assertion. Even amongst Christians

I think that was a problem because people don’t understand how democracy works. First, the people have to give to the Parliament the authority over a particular area of responsibility, then the Parliament decides what legislation should be enacted within that area of responsibility. The proposed change was crystal clear that this was the order. Demanding a detailed plan of how the Voice would operate was an effective wedge by the No campaign, knowing that it would be a powerful incentive for doubters to vote No, but also knowing that it would be improper for Albanese to undermine the Parliament by prejudging how it should respond.

“The Voice was a modest request, deliberately modest, scaled to be so small, out of regard and love for the wider Australian community. We refused what the First Nation’s people asked for, even though it was so little.”

John, please read Waleed Aly’s column in Fairfax today. In a nutshell, his view was that there were a quite a series of hoops we each had to go through to reach the conclusion that this modest, little thing should go permanently in the constitution rather than adopt multiple other measures that could address the underlying problems. In a previous column of his, he commented that the arguments required for non-indigenous people to agree with the Voice required them to accept an underlying narrative about Australia that most, frankly, do not. Where does the argument that we “should” have voted YES actually get us as a nation now (rather than simply be some salve on the grief wound of a YES voter). I just do not see any point in attempting to make 61% of the voting population feel guilty for their voting choice.

Hi Steve, thanks for your comment. Both sides of the Voice debate could try to make the other side feel guilty. For example, the “No” case accused the “Yes” camp of fomenting division. But there’s little point in pursuing those arguments now. The best part of Waleed’s piece is the argument that Australians like to see people treated equally, which explains the differing results in the marriage plebiscite and this referendum. That’s quite a powerful argument. Thanks for pointing me to it.

The case made for equal treatment probably explains some of the lack of rejoicing in the “No” camp. Is it still worth noting contra Senator Jacinta Price, that the remote communities voted strongly for the voice? Sorry to disagree, but I do think it is worth noting. No salve on the wounds for those Yes voters. Your implied point that the rest of us non-indigenous no voters should not fixate on our feelings has weight.

Hi John , I enjoy your posts. You bring to light views that I aren’t aware of from the Multi Denominal Christian community. This is helpful to understand our walk in Christ in these times. It gives me a feel for the pulse of the community. Keep up the excellent work , fearing not to tread where others wont. GBY ♥️♥️

I was convinced to vote NO by Megan Davis and Marcia Langton

I was convinced to vote YES by Megan Davis. I find it hard to accept that reasonable, open-mined individuals who took the time to read or listen to this compelling essay, would want to deny the request of First Nations people to opportunity for a representative body to advise the government on matters that affect them. I feel very sad, and can only try to imagine the despair of countless community leaders like Megan, Noel Pearson, Marcia Langton, Jackie Huggins who have devoted their lives to gentle advocacy for a fairer go for their people.

https://www.quarterlyessay.com.au/content/correspondence-megan-davis

corrected link to Voice of Reason

https://www.quarterlyessay.com.au/author/megan-davis