On a hill overlooking Lake Macquarie, on the Toronto peninsula that juts like a dagger into the lake, sits the Toronto Pub, a grand stone building festooned with colonial lace. The tourists and revellers that throng the pub don’t know it, but they party on the site of missionary Lance Threlkeld’s Ebenezer mission.

Here the first book of the Bible was translated into an Aboriginal language: Luke, rendered in Awabakal spoken by the peoples of the Hunter by Threlkeld and Biraban, his teacher.

As I read David Marr’s Killing For Country, it seemed to me that the stone hotel supplanting Threlkeld’s wooden huts was a metaphor for the story of dispossession that Marr tells.

Threlkeld, the “splendid missionary” in Marr’s description, appears like a wraith in Killing For Country seeking justice for murdered aborigines, attempting to provide a place of shelter, whistleblowing the accounts of massacres, reporting the rape of Aboriginal girls whose “night shrieks” he could hear from Ebenezer.

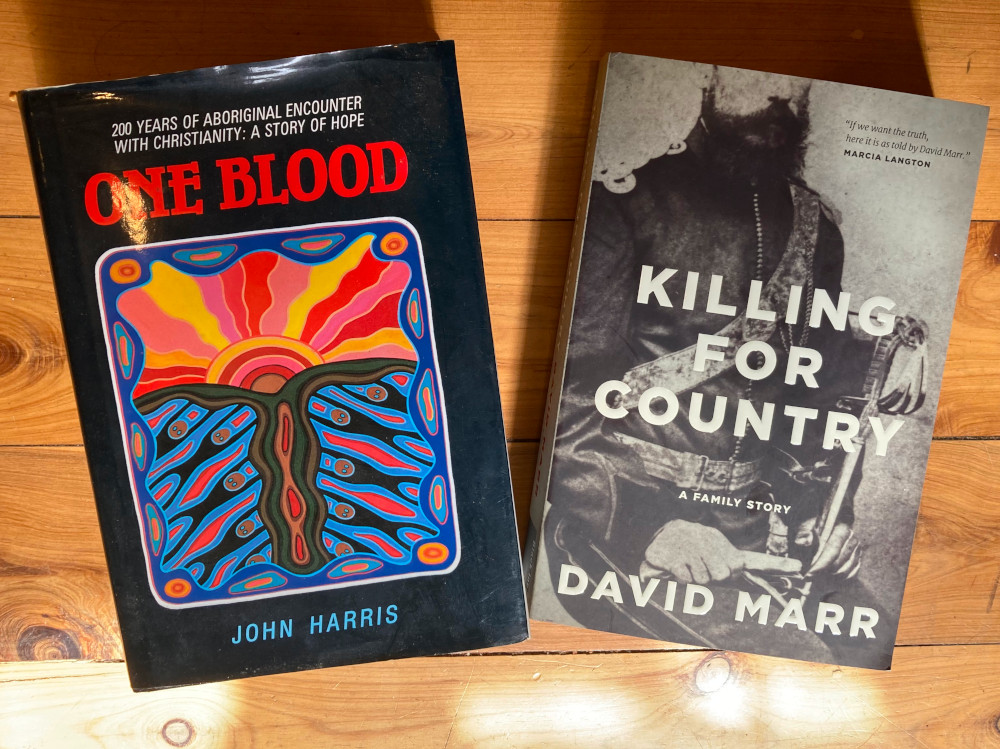

But Threlkeld is a loser in the world’s eyes. He had been sacked by the London Missionary Society, which thought his mission too expensive, apologising later when it was too late. Ebenezer was abandoned because, literally, there was no Awabakal left. And Threlkeld’s translation was destined to be unread – the first Bible translation in Australia. A fuller picture of Threlkeld comes from One Blood, John Harris’ magisterial history of Christian interaction with Indigenous people across Australia.

These are contrasting histories. Marr’s history is about the strong men of white settlers, (many of whom claimed Christ as their Saviour at least in name,) and their succumbing to weakness, ambition and land lust.

Harris’ book features the weak of the white settlers, like Threlkeld, and the spending of their strength, powerless in the face of the squattocracy.

The weak, of course, are the strong. Bearing in mind that both books foreground white people – the indigenous-written histories are the emerging frontier of the history debate.

Both books are about dispossession and the failure of many Christians to be Christian. Especially those of wealth and title. But Threlkeld is not the only wraith in Killing For Country – some are almost invisible in the telling.

When the Presbyterian John Dunmore Lang sets up a local branch of the Aboriginal Protection Society, in the wake of the Myall Creek massacre, the message from the society’s London headquarters is too strong for colonial society to bear. The society fails. But Lang, like Threlkeld, is one of Marr’s (and Harris’) tragic heroes.

The Londoner’s credo recounted by Marr was “By fraud and violence Europeans have usurped immense tracts of native territory paying no regard to the rights of inhabitants.” The minds of the colonists could not comprehend the idea that the indigenous people had rights to the land.

Describing the Londoners Marr records, “as its meetings were held in Exeter Hall in The Strand, Exeter Hall became squatters’ slang for everything they despised about sentimental British humanitarians.”

There’s a wraith buried in that par. Exeter Hall, which could seat 4000, is described as “A building in the Strand, London, which was erected c.1830 and used for religious and philanthropic assemblies, esp. by those of Evangelical sympathies, down to 1907,” in the Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. It was where the British and Foreign Bible Society, the evangelical Protestant Reformation Society, and abolitionists like the Anti-Slavery Society met. A mix of evangelical zeal and social reform emanated from the hall in its heyday.

But as much as Christians want to focus on our heroes who protected Indigenous peoples heroes, such as Threlkeld, Matthew Hale of Poonindie in SA, and John Gribble of Carnarvon in WA and Warangesda in NSW featured beside less worthy people in One Blood, Marr points to the many Christians who succumbed to self-interest.

Marr is paying penance for his ancestors in writing this book, “I had to tell the story of my family’s bloody business with the Aboriginal people.”

But the unvarnished history of war, dispossession, rape and torture he and other historians have laid bare is simply the truth. It should not only weigh on those with ancestors who slaughtered other humans, like Marr himself.

‘