An Obadiah Slope Column

The Allied Dead: A temple Obadiah visited by mistake in the Kyoto foothills was the most moving event of three weeks in Japan; we ended up at the Ryozen Kannon Temple, not famous and not ancient – it dates from the 1950s, and features a giant concrete statue of Kannon, the Goddess of Mercy, not Buddha as Obadiah thought at first glance.

(We were trying to head from the awesome Kiyomizu-dera temple, an awesome hillside complex thronged with locals, to the Kōdaiji Temple with the raked stone and moss gardens of Kyoto tour brochures)

But Ryozen Kannon held a surprise – actually two. Behind the statue building a pavilion contains urns of eath from soil from Allied cemeteries from the Pacific theater of World War II; and a series of card cabinets has the names of Allied prisoners of war who died in Japanese captivity.

(In the main building are the memorial tablets to some 600,000 Japanese war dead – the Allied dead names were added when a memorial to the unknown soldier was added soon after.)

As Obadiah, who was born the year the temple was built, reflects on this unexpected even-handed memorial site, run by Buddhist monks who remember the dead four times a day, he recalls a Christian man who adopted him and his twin, both half-Japanese. Captain Colin Sandeman had been sent to fight the Japanese in India and served in Dimapur, one town short of the slaughter of the Japanese advance into Nagaland.

But then he adopts two boys who must have reminded him, daily, of the people he fought.

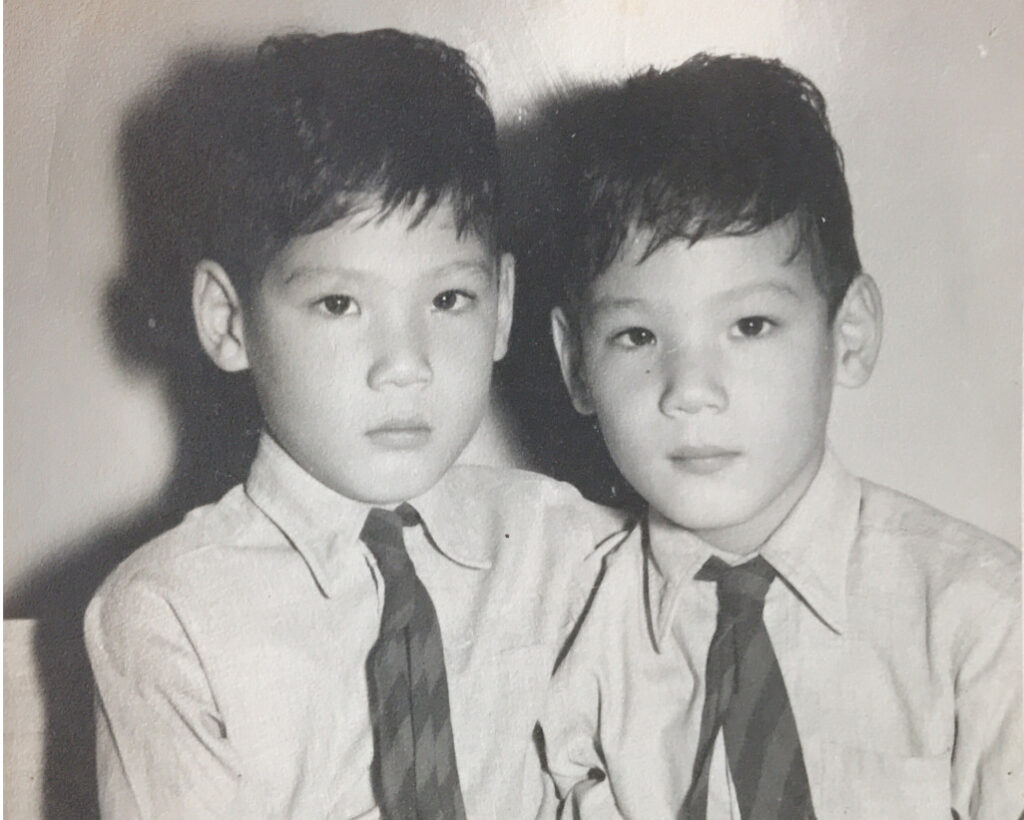

Two little boys. Obadiah (John) on the left, Peter on the right.

As Obadiah lies on a futon in a traditional Japanese house on a Japanese Island in the inner sea, Naoshima, he remembers the British soldier who was prepared to accept him despite the war. Ever since, he read, “For those who are led by the Spirit of God are the children of God. The Spirit you received does not make you slaves, so that you live in fear again; rather, the Spirit you received brought about your adoption to sonship. And by him we cry, “Abba, Father,” (Romans 8:14–15); Obadiah has been grateful for being doubly adopted.

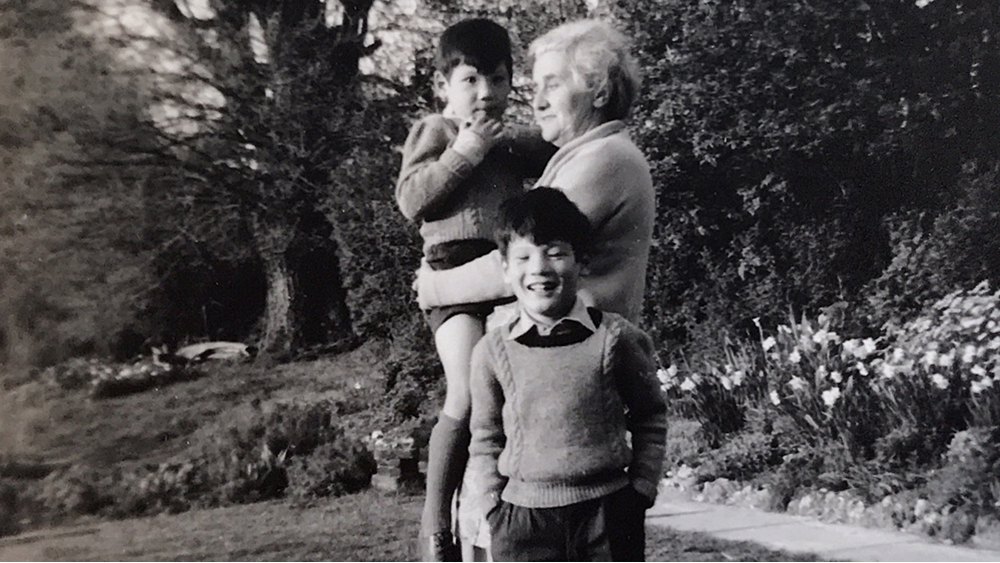

And here we are again, with Ethel Mary Sandeman, who became our mother – I am the shy one again.

###

Sydney’s designer link to Naoshima: And having been adopted by an architect, here are some Obadiah architectural thoughts: Arriving by ferry to Naoshima, the “art island” in Japan’s inner sea, Obadiah is immediately struck by the ferry terminal – a work of exquisite minimalism. A flat metal roof, supported on a gridded forest of too-thin poles with several glass boxes for a waiting area and shops, and a place for cars and trucks to line up for the ferry, and a bus station it is perfectly balanced, a jewel of a building. If it was not already the title of a novel, the unbearable lightness of being would sum up this construction, which allows space to flow through a collection of functions that logically should not belong under one roof. Especially on as beautifully constructed as this.

Now, where have I seen it before? It took a quick Google, but the answer is in Sydney. The Naoshima Ferry Terminal is an early work by SANAA, the architects who designed the new North building of the Art Gallery of NSW.

If you want to watch the ferries come and go against the dramatic backdrop of Japan’s inner sea, including the 13km of bridges that link Honshu and Shikoku, as Obadiah did, SANAA provides the same mushroom-shaped seats to sit on that you can wait for friends to meet you at the new building in Sydney. Every time a ferry arrives, a man scurries down the pier on his bicycle to haul in a rope at the stern of the big roll-on roll-off ferries. To Obadiah’s eyes, it is Sydney Harbour redrawn by a Japanese painter.

I fell in love with the Ferry terminal instantly. It took a couple of visits for my love for the Sydney building to blossom.

Naoshima Ferry Terminal photo credits 663 highland/Wikimedia, 準建築人手札網站 Forgemind ArchiMedia

A more conventional treatment of Naoshima would feature Tadao Ando, who makes concrete and steel float, and then sinks his work into the earth. He turns solid reinforced concrete walls, precisely finished, into modern versions of rice paper screens. But the tour guides will give you all of him – and he is a truly inspiring architect. Obadiah is being willful, ignoring an Island populated with significant Ando works for the ferry terminal, but he’s like that.