Pentecostalism, now the second-largest Christian movement by attendance in Australia, owes its birth to women ministers. Barry Chant, a great historian of Australian Pentecostalism, points out one great distinctive in his Phd thesis: “Of the eighteen Pentecostal churches founded in this country up to and including 1925, eleven were planted by women. Of the 37 churches established by 1930, over half (20) were started by women.”

Alongside the biblical debates about complementarian or egalitarian views of women’s ordination, we should consider the sheer scale of women’s contributions to Australian Christianity. Chant points out that the contribution of women in founding Australian Pentecostalism sets this nation’s movement apart from others, especially the US:

Winifred Kiek (1884?-1975), ordained a minister in the Congregational Union in 1927, serving in the new Colonel Light Garden suburb, is often regarded as Australia’s first ordained woman.

But perhaps the pastor of Australia’s first Pentecostal Church, Janet Sarah Lancaster, should take the honour – although she may not have wanted any prominence. Although a denomination did not formally ordain her – she simply pastored the first church of a new movement.

“Wherever we look in the first twenty years of Australian Pentecostal history, the imprint of Sarah Jane (Jeannie) Lancaster (1858-1934) can be found,” Chant writes in a chapter devoted to Lancaster which The Other Cheek draws on for this piece. “It is not, at first glance, obvious. Her ministry was humble and unobtrusive. No published photo of her appears in over 25 years of printing and distributing magazines, books and tracts. Articles written by her were rarely signed. Yet she did publish the photos of others and always gave credit to other writers when she published their works. She was not ambitious for position or human acclaim. Much of what she did was deliberately kept discreet.”

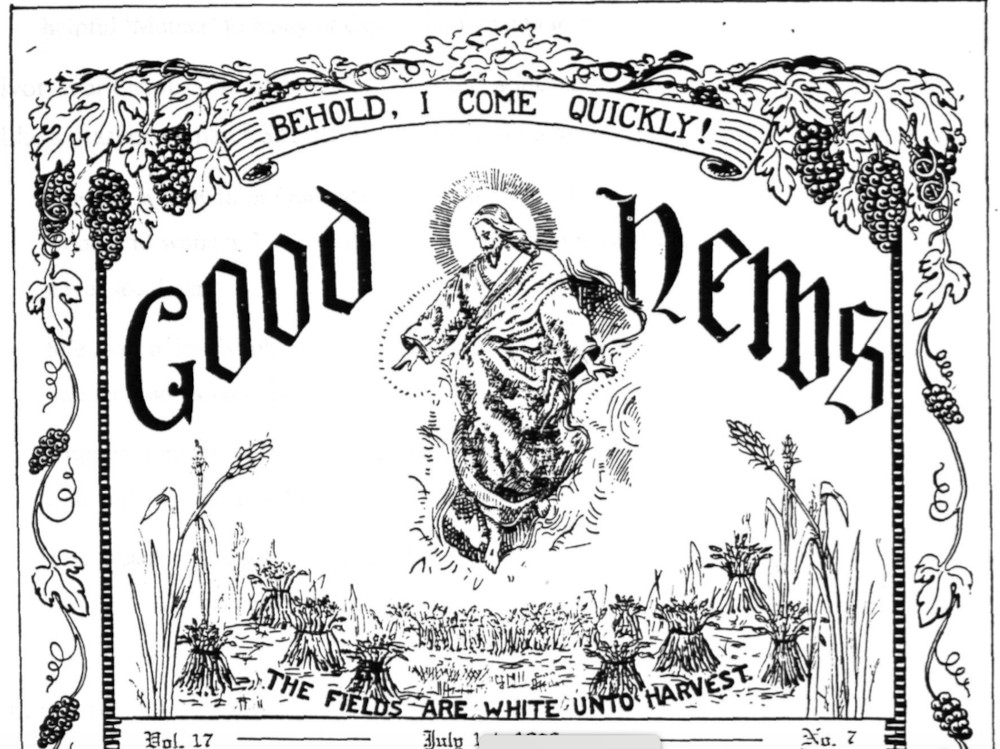

In 1909, Janet Lancaster purchased a temperance hall in North Melbourne and established Australia’s first permanent Pentecostal church. “Her Good News hall became a focal point of Pentecostal preaching and activity until it closed its doors in 1935, ‘ Stuart Piggin and Robert Linder write in Attending to the National Soul.

“Good News Hall seated about 300 people, and was usually attended by about 100 on Sundays.” Chant records. “Across the front of the building, above the platform, was boldly painted the text, ‘The Lord God Omnipotent Reigneth.’ During the week there was plenty of activity. The Hall was always open for prayer and prayer meetings were held regularly. The building had a number of smaller rooms, including a living apartment for the Lancasters. Consequently, people would often go there to stay for a few days or even a few weeks. During this time they prayed and studied the Bible, seeking deeper spiritual experience. There was a Bible, Book and Tract Room.”

After Good News Hall closed, the Eureka youth movement, part of the Communist Party, rented the Building. Eureka Hall became a major jazz venue hosting Graeme Bell’s Dixieland Jazz Band. It is now called Magnificat House and, fully restored, is owned by the Catholic society, the Legion of Mary.

But Lancaster was not confined to North Melbourne. After Good News Hall was set up, she sent out evangelists, many of them women. “From Perth to Cairns, she was involved in evangelism, church planting, preaching and prayer. She proclaimed the Word on street corners. She handed out tracts. She talked with strangers. She conducted meetings in halls and houses. She communicated with people of all ages. She edited a magazine. She published thousands of tracts. She engaged in welfare work with the poor. She prayed for the sick. She encouraged people to be filled with the Spirit. She eschewed the things of the world for the things of God.”

“By 1925, there were congregations to be found in Adelaide, Ballarat, Brisbane, Cairns, Mackay, Melbourne, Nambour, Parkes, Perth, Rockdale and Rockhampton together with numerous homegroups in places like Burnie, Freeburgh, Heidelberg, Lilydale, Springvale and Wonthaggi. She personally visited virtually all of these at some point, teaching, encouraging, praying and exhorting, as she did.”

Pagiin and Linder note It was Lancaster’s Good News Hall that sponsored Pentecostal superstars Smith Wigglesworth and Aimee Semple Macpherson to come to Australia, tours that fuelled the expansion of the movement. But these historians do not think that Lancaster’s chief contribution was organising those extremely significant visitors buty in encouraging the ministry of Pentecostal women.

One example – out of many – is Florrie Mortomore (1890-1927), who was baptised in the Spirit in Good News Hall as a nineteen-year-old. Chant describes a young woman who “showed daring and enterprise by exercising a ministry normally felt to be the province of men. She seems to have cared little about traditional concepts of ministry. For her, it was sufficient ordination to be anointed by the Spirit of God and to have the Good News to preach. Armed with her Bible, a deep sense of compassion for the lost and needy, a strong faith in the miracle-working power of God and an earnest desire to see Christians filled with the Holy Spirit, she travelled far and wide as an ambassador for Christ. In the 1920s, she established — or helped to establish — as many as seven congregations. Her ministry resulted in missionaries going overseas.”

“Although she died at the young age of 37, Florrie achieved more for the kingdom of God than most people manage to do in twice the time.”

Attending to the National Soul records that “Mina Ross Brawner gave 28 years of Ministry to Australia.” first as a Seventh Day Adventist missionary, then after a Pentecostal experience at Aimee Semple McPherosn’s Angelus Temple in LA, she returned to Australia with a medical degree. “She worked again in Australia from 1927 to 1943, holding evangelistic meetings in Sydney, Ballarat, Melbourne and Brisbane. She visited prisons, set up food distribution centres and soup kitchens for the poor, and established fourteen churches and two Bible colleges.”

It was not a glamorous life. Chant details years of struggle and hard work. For example, “At the end of 1928, Brawner organised a tent campaign in Mosman, New South Wales. Brawner herself assisted Jotham Metcalfe and some of the men as she ‘pulled ropes, drove stakes, sawed boards, and did a man’s work all week.’ The holiday season was not the best time to open a campaign, but by mid-1929, she could report that she had preached 85 times in the tent, that there was a group of 25 to 30 people meeting regularly and that 24 adults had professed conversion in addition to many children. These figures could be trusted, she said, because she would ‘never inflate a report.’ She only counted those as converts who she had reason to believe had a ‘real experience’ of the Lord.”

The contribution of Lancaster and her sisters does not settle doctrinal debates over women’s ordination – although it is clear that God worked through them. How else can we explain the conversion of thousands? But it settles the question of whether women are effective leaders and planters of churches. The historical record bears it out.

Image: Janet Lancaster’s “Good News magazine” 1927, Image credit: from Barry Chant’s PhD Thesis

Thanks for posting this article. Rev Dr Barry Chant’s thesis is definitely worth reading in it’s entirety!