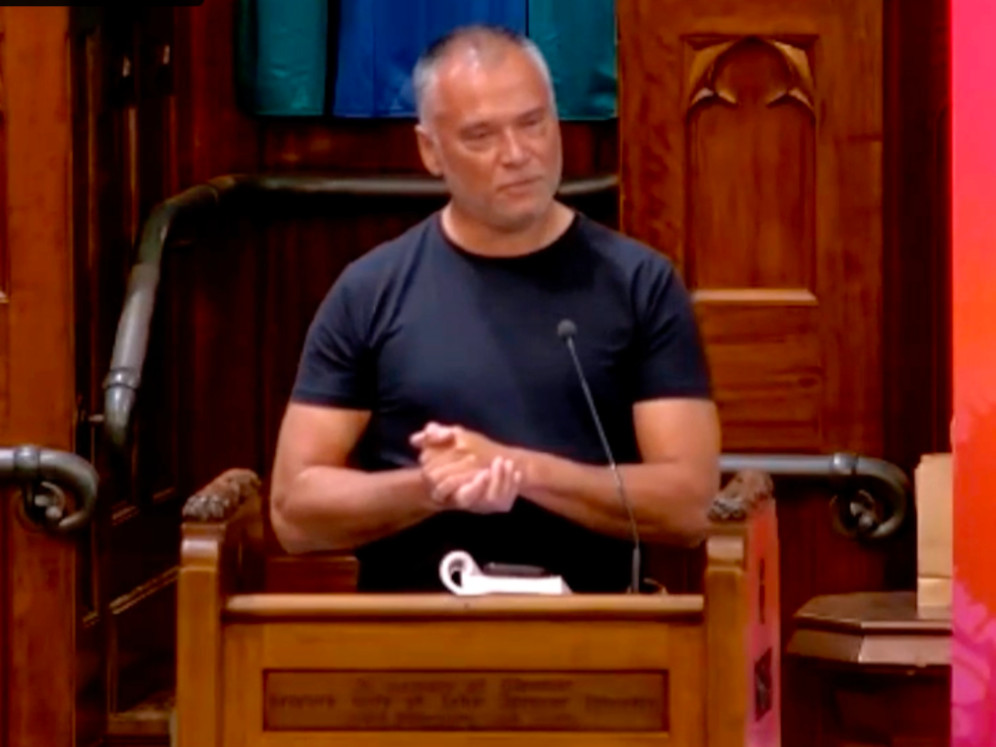

Stan Grant was part of this year’s lineup at PreachFest, a unique celebration organised by the Uniting Church in NSW/ACT. The three-day festival was “created to inspire and enliven the craft, art and vocation of preaching across churches in Australia.” and draws speakers from many Christian traditions. Grant’s message has been posted in full as a video, and this is a transcript of part of it.

My great-grandfather when he was a little boy, was gifted the stump of a ceremonial carved tree by his mother. The land was being cleared as my people were being cleared. His mother was born into a time of war.

What today we know as the Bathurst wars, but what were at the time described in the newspaper of the day of the Sydney Gazette, as the exterminating war, the exterminating war on the Wiradjuri people martial law was declared no one would be prosecuted for killing my people. Within three years, about 90% of our population was wiped out. The trees were wiped from the landscape as new buildings took their place, and we were forced onto the margins and my great-great-grandmother rescued our tree, a scarred tree with each incision marking another part of my family’s story, who we are. My great-grandfather carried that tree with him Everywhere he went, he would go into different aboriginal missions and reserves and put the tree stump down, light a fire and call people to hear stories.

They’re people of stories, people of God, people of faith, people of faith for whom words meant everything. These are the people that I was born into: the storytellers, the keepers of faith. It’s lovely to be in a building like this; it’s lovely to be here and to share this space with you, but this was not the church I was raised in. I was raised in a black church, a church that white people who went to church uptown didn’t step foot in ours. If anything was a church of the forsaken, it was the church of the crucified Christ. It was the church of people who cried out, my God, my God, why have you forsaken me?

And it’s the church where we never ask, “Is God real?” That would be impossible for a Wiradjuri person. I walk through God’s cathedral every single day, and in the bird song, I hear God’s choir every single day. We don’t ask, “Is God real?” But we had to ask. We had to ask, “Does God care for the forsaken, for the abandoned, for the afflicted? Where are you God?”

I remember looking into the bedroom at my grandmother’s tiny little house, two bedrooms, and my uncles were kneeling around her bed, and their bibles were open, and it scared me as a young boy looking at these men of profound, unshakable faith. God filled men praying with a ferocity that made the walls shake because it was a prayer that came from abandonment.

It was the prayer of why God, how God, it was a prayer to survive. I’ve never forgotten that moment. I’ve never forgotten what it was like to be among people for whom God was not a word. A prayer was not just something we did out of politeness, what we just did in church, it was survival. It has stayed with me my entire life just as the memory of watching my uncle preach in that little white wooden church on the mission, fire and broom, stone preacher who would mop the sweat from his brow with a handkerchief and point his finger to make sure that he underlined every single word and it always landed on me, always landed on me, and I’d squirm, and I’d get a headache, and I’d want to get out of there, but I knew the presence of God and I think my uncle knew, and when he pointed at me he wanted those words to land on me.

It was like he knew that those words were all I would have, words are all my people have had the words to try to speak back, love to a country that had shown no love for us, words that may even speak to people of God who could not see God in us, people who carried the Bible, people who preached the word of God were the same people who joined the frontier, raid parties to wipe my people from the face of the earth. Reverend Samuel Marsden, who was the New South Wales Church of England chaplain, a man of God who got on his knees every night and prayed to God, described my people as the most degraded of the human race. He believed we were irredeemable. Marsden, like so many, believed he was on the side of God, and yet he could not see God when God was staring him in the face…

He describes his life in media and how he got tired of it, and was glad he did not have to cover the referendum result.

I’ve made a decision to walk away from that and listening to the words of politicians and activists and commentators trying to capture this moment, these inane, pithy comments reducing all of the complexity of our lives down to some polled media, tested political speak, and I wondered, where were my people in these empty words? Words of triumph or words of resentment. People who lectured to us that we must be a unified country and we must forget about this history. We must forget this grievance, erase my ancestors and their pain and then other people telling me we should never have trusted white people in the first place. This is what white people always do. The equally inane political language of resentment. I can’t find a home in triumph or resentment. I can’t find a home in a yes or a no because these things are not the answer to the pain in our souls…

Words like love, and truth, and justice words that appear over and over and over in the scriptures. Words that call us to account words like afflicted. I have really pondered this word affliction this year. What is it to feel afflicted? Simone Weil, the great French philosopher and mystic, who herself said that she felt the spirit of Jesus Christ into her body. She was never baptised. She felt she was never worthy enough to be baptised, but she said she felt the spirit of Jesus enter her, and she said, “Affliction is the cold hand of fate. It is the chill of indifference.” Think about those words, the chill of indifference. We don’t have to care about the people who suffer.

She said that affliction chills us to the bone. It steals our humanity and turns us into things. Simone Weil really challenged me to try to understand where God is in our affliction. I know God’s real. Where is God when we suffer? And she said, “Sometimes God has to leave us so that we can exist.” It’s a hard thing to think about that God may leave us, but if you think about the worst things that we can do to each other on this earth, you have to ask yourself, where are you? Why don’t you stop this? Isn’t this what the book of Lamentations was talking about, perhaps when I was a boy? The book that spoke most profoundly to us, the afflicted, the abandoned. In the Book of Lamentations, Jerusalem has been raised to the ground. People are so hungry they have to eat their own children…

And sometimes, in that affliction, we don’t always get an answer, or we don’t get the answer that we want, which is to stop this, stop it now. Because if we just heard before, sometimes it is in that suffering that we have to stop and stop asking the questions and allow God to speak to us. That’s what I do. Every morning, I try to ask God to speak to us, [about] affliction, lament, the importance of lament, the importance of stillness, of quiet, of just sitting with the reality of something and not trying to fix it, heal it or reconcile it, but sit with the full weight of it and in that lament be still and know that I am God.