Sometimes, the Bible term “A Cloud of Witnesses” springs to life – especially when the deeds of those who have truly put their lives on the line for their faith are discussed. This was certainly the case for a talk by Colin Reed, a veteran Church Missionary Society (CMS) missionary, gave at the Moore College Library. Video Link.

Reed had evident joy in recounting the exploits of Australians who served the churches of East Africa. But he began with a German Lutheran.

“Well, I’m going to start with the Bible, which is a very good place to start. The first missionary of any society in modern times to arrive in East Africa was Johan Crop, a German Lutheran serving with CMS Britain. I can explain that later if you like. He arrived in Mombasa in 1844 having previously been a missionary in Ethiopia with his wife Reina. Soon after they arrived in Mombasa, she had a baby and died and the baby died as well in childbirth. The first thing that he was anxious to do was to do what do you think translate the Bible into Swahili. And within a month of arriving in the country, he began a translation of the New Testament into Swahili. Understandably, it wasn’t actually a brilliant translation, but he was very anxious that if he died people would have the Bible.”

Reed decribed how the Bible translation baton was taken up by a better linguist, the anglo catholic Edward Steere bishop of Central Aftica, together with the CMS’ Johann Ludwig Krapf.

“But those Anglo-Catholic missionaries also, their first concern was to make sure that people had the Bible,” Reed said. We then got a wonderful insight into translating the Bible into Swahili (a lingua franca for East Africa, with Reed pointed out has a strong Arabic influence. Gesturing to the Library exhibition Reed added “There’s a Swahili version of the Bible produced in 1914, … looking at the title of that Bible produced in 1914, it starts with the Swahili word, which I’d never heard.

” So I looked it up and it is in fact a word derived from the Arabic for holy writings and it usually applied to the Quran. And so when the people were doing that Swahili translation, they took a word that they thought might be a useful word, but the question is what other connotations did it carry? I don’t know. Those are the sort of enigmas that people translating have to deal with.”

He gave another example – the local hymnbook. “Inside it it says, for those of you who speak Swahili ‘hymns that are used in the worship of Almighty God anytime in the mosques and in houses,’ and again people [were] trying to do connection with the Arabic culture of the Swahili language. Most of the religious language of Swahili comes from Arabic. Swahili is a mixture of Bantu and Arabic languages, but I don’t think anybody ever thought of calling churches mosques, but obviously the people who wrote that original hymn book thought people are used to worshipping in the mosque when they come to church, we’ll call it a mosque.”

And then Reed jumped ahead to his final time as a missionary “My wife Wendy and Iended our working career in Iringa in the south of Tanzania where we taught in a Bible college and I was also on the staff of the cathedral. The cathedral was a new building designed by Fiona Oates, a CMS Australia missionary architect built by David Break, A CMS Australian Missionary Builder, a modern new building built in the old grounds that George Chambers, the first bishop of Central Tanganyika acquired back in 1927 and George Chambers consecrated the first Anglican church in Iringa in 1930. It is now stands in the grounds of the cathedral. It’s a simple little mud building.”

And with that segue, we are talking about one of the people who linked Australia to East africa missionary wise.

“Over there in the display, there’s a 10-page letter from Wilson Cash, the Africa Secretary of CMS UK asking CMS Australia to take responsibility for running the Anglican church in Tanganyika. Basically the mission in Tanganyika, and this is George Chambers reply: ‘This council is the opinion that the present wonderful opportunity in Tanganyika offers a challenge to the CMS of Australia and Tasmania that cannot be refused. We therefore believe that this is the leading of the Holy Spirit.” Reed continued “And so it was agreed that CMS Australia would care for Tanganyika as it became after the first World War”.

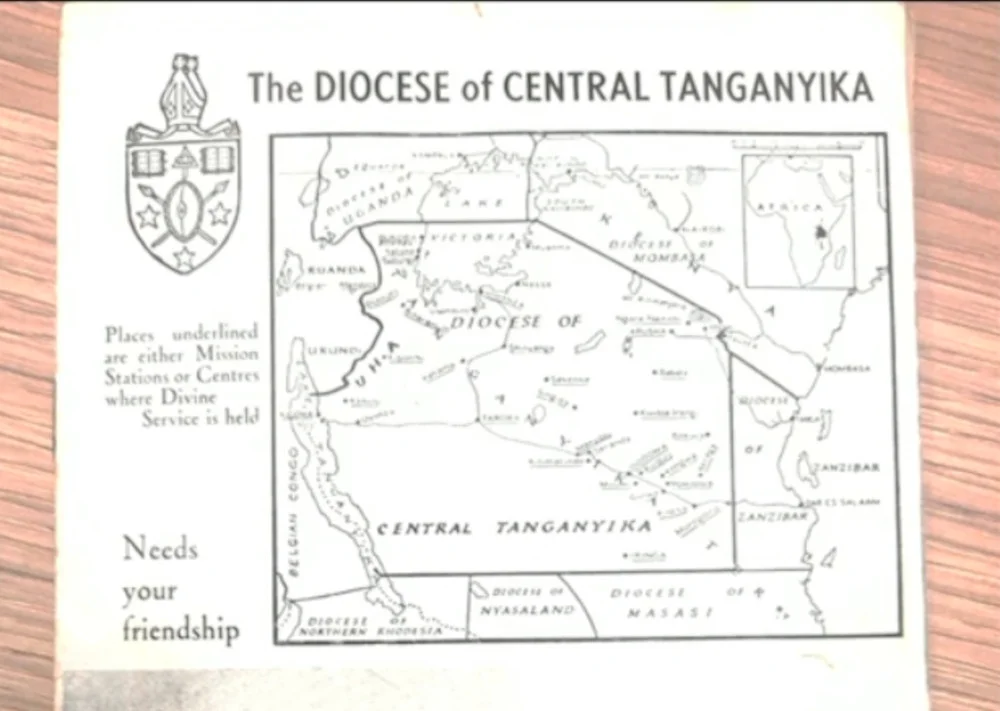

The extraordinary George Chambers made this “wonderful opportunity” real. He had already been Deputy Principal of moore College, and founded Trinity Grammar, which he took care to get out of debt on becoming the first Bishop of Central Tanganyika. That diocese covered most of inland Tanganyika.

“He went to be consecrated in England. Then he went back to Tanganyika, taking with him twelve new missionaries and here’s a letter from his wife in the archives describing how they arrived by train, because the Germans had built a train during the German era, ‘we were glad to leave the heat of Dar es Salaam and climb to the central plateau. It was really marvellous to leave the coast at 2:50 pm and be in Mvumi 35 miles from Dodoma by 12:30 next day having travelled in good sleeping births and had meals in a comfortable dining car on the train. What would [early missionaries] Livingston and Hannington and Mackay have thought if they could have seen our trouble free progress?’

And here Reed starts producing books that he is donating to those archives, sketching out the lives of these men, and placing their books on the library lectern.

Reed lifts up a red-covered book and reads the title “David Livingston Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa, but he ended up, of course in Tanganyika on the shores of Lake Tanganyika where he was found by a certain Henry Morton Stanley.”

Lifts another book, glances at the spine to make sure he had the right one. “Bishop Hannington, the first bishop of Eastern Equatorial Africa, CMS UK missionary. These guys walked thousands and thousands of miles. First of all, he walked through Tanganyika, then he went back to the coast and was made bishop and walked from one side of Kenya to the other and got to Uganda where he was going to be bishop to be killed on the orders of the king of the Baganda people whose seers had told him to beware of foreigners arriving from the East.”

Places the Hannington tome on the Livingston one. Picks up another book.

” Alexander Mackay, one of the early CMS missionaries in Uganda who died on the shores of Lake Victoria and was buried near Mwanza in Tanganyika, [now] Tanzania. There you are three additions to the archives.”

Reed circles back to the Aussies.

“George Chambers had many gifts, but he had two, I think, specific gifts, one of which was to challenge people and call people to go and serve God, not just issue general invitations, but to call people individually and say you should consider. And the other thing associated with that was that he had a great gift for challenging people about money and he would go to business people and say, we need this amount of money and I think you’re going to give it.”

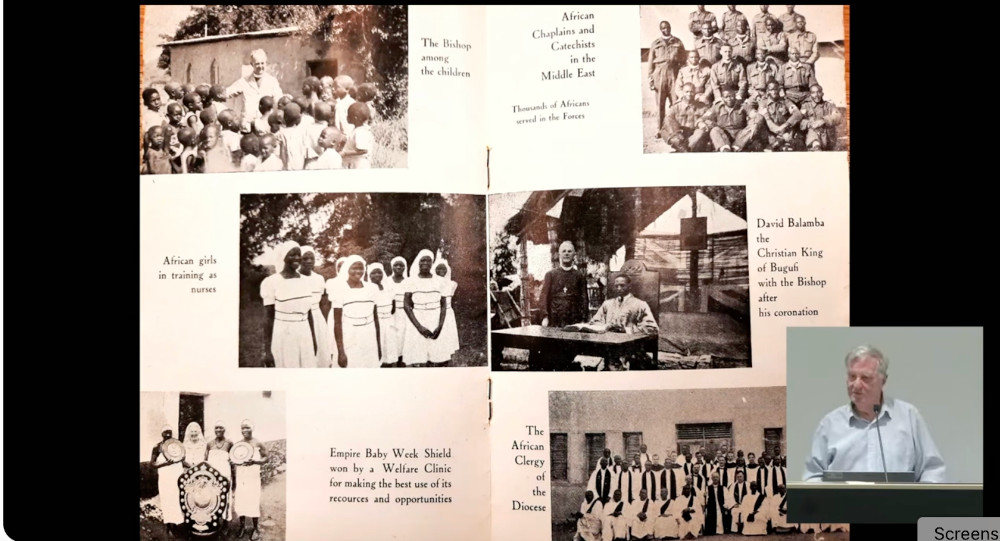

Reed shows a page from the Central Tanganyika newsletter giving an insight into Chamber’s day to day life in Africa. “There’s one central page from one of these diocesan newsletters, and I just thought this was so fascinating. Winifred Chambers, his wife came from Wales. Her father was a canon in Swansea in Wales, and then he moved to England and she spent a lot of the time living in England with their two sons for the education of their children. So he was often on his own. He loved children, he loved doing things with children. So there he is with a group of children. Then there was this nurses training school at Mvumi. Underneath is a missionary receiving an international award for teaching people baby and childcare. And then at the bottom there are the clergy of the diocese.

“And that fascinated me. He went to the kingdom of Buguli to crown the king of Buguli. I didn’t even know there was a kingdom of Buguliin Tanganyika. The British never got rid of indigenous kingdoms…

So it’s interesting that the bishop went and crowned the Christian King of BofI, which is in northwest of Tanika … And then on top of that, here we are in 1944, shepherding German mission congregations. ‘In spite of our unprecedented shortness of staff, I’ve offered the government to supervise and care for one of the German missions with five stations in this diocese. All the Germans in this mission except one lady, have been repatriated to Germany being strongly Nazi, and the therefore African congregations are shepherd less and liable to become resentful.’ “So he goes on to say, ‘oh, that men at home would realise the need in this diocese for strong reinforcements while winning the war in Europe. We may be defeated here. We may not be defeated here. The issues of this war are spiritual. You need to make sacrifices.’ Amazing. “

In contrast to Chambers there were missionaries whose life were cut short. “William Wynnn Jones, [was} Teacher at Trinity Grammar School, [and] curate to George Chambers at Dulwich Hill. Went to Tanganyika 1928, just a year after George Chambers, married Ruth Minton Taylor, became the next bishop of Central Tanganyika, 1948 to 1950. And he had an accident. He got a puncture in the car, he was taking the wheel off, kneeling down by the car, and another car ploughed into him and he died of his injuries. He was buried in Dar es Salaam and Bishop Mdimi Mhogolo arranged for him to be exhumed and reentered in the cathedral in Dodoma because he was the bishop of Central Tanganyika.”

Presenting a first edition copy of Paul White’s Doctor of Tanganyika to the library, Reed revealed the struggl behind the man known as “The Jungle doctor” and a significant force in establishing the gospel witness of AFES (Australian Fellowship of Evangelical Students). “Paul White. He went to Tanganyika in 1938. He was only there for three years because his first wife, Beatrice, suffered mental health issues, severe depression, came back to Australia and she spent a lot of time in care. He had terrible asthma. So they were only there for three years, but he went on having an enormous influence for years afterwards with his great interest. His books on Doctor of Tanganyika Jungle Doctor, [and} his radio broadcasts.”

And then a final excderpt on Neville Langford Smith. Reed began by tracing connections with him and then the man’s spiritual struggles. “Guess what? He went to Trinity Grammar School. Guess what? He was taught by William Wynn Jones at Trinity Grammar School. He became dux of Trinity Grammar School. His father Neville Langford Smith’s father was a canon of Sydney diocese, one of those sort of movers and shakers .Neville grew up here in Sydney and went to Sydney University same time as Paul White, more or less Sydney University, Evangelical Union. Those influences went to Tanganyika because George Chambers challenged him to, and first of all, he said, ‘yeah, I’ll come before I finish my degree.’ And George Chambers said, no, stay and finish your degree at Sydney University first.

“So he did. And then he wrote to Chambers and said, I’m ready to come. And Chambers sent him Telegram saying, come now, don’t bother to get accepted by CMS. I need you now. So he went off to Tanika without the backing of CMS. George Chambers said, I’ll give you your keep, won’t give you any money, but I’ll feed you.’ And on that basis, he went to Tanganyika and stayed in East Africa for the next 45 years. And he was a great friend of my parents. My father worked with him when my parents were missionaries in Kenya. And then he was my bishop, my wife’s and mine for ten years when I worked in the Diocese of Nakuru in Kenya. And then in his old age, I used to visit him often in Mowll Village before he passed away.”

Reed gave a warts and all account. Despite being called to Tanganyika by George Chambers, Neville Langford Smith fell into conflict with him and William Wynn Jones .

“He got to Tanganyika and came into conflict with them because he was a strong character too. And they sent him back to Australia and said, ‘we don’t want this guy in our diocese.’ And what did he do? He took it to God and said in his book, he says, ‘God needed to break my proud spirit.’ And he let God do that. And he went on to serve and his health was bad. Paul White told him, you can’t go on serving in Tanganyika because you’ve got persistent malaria. So CMS said, you can go and serve in the highlands of Kenya in the healthy Highlands of Kenya instead. And that’s what he did.

But behind this cloud of witnesses was the Holy Spirit. Reed picks up Neville Langford Smith’s book and reads: “‘Over the years, I’ve suffered from nerves whenever under pressure, but was unwilling to let it be known. The wonder is that God has been pleased to use me in his service despite the mistakes and sins and shortcomings. I’ve always had a strong sense of God’s call. The doctors knocked me back when I offered to CMS. It was because of a nervous disorder, but I went anyway. The call of God was strong. I didn’t want to be a bishop. I felt the job was too hard for me. I probably went about it the wrong way and things might have been better if I’d gone about them in a different way. I was hard on people. I scolded them like I sometimes scolded my wife, Vera. I took Vera for granted.’ When I used to visit Neville in his old age, he’d become such a gentle old man.”

“And I remembered him when he was bishop of this large diocese and a very active man. And he said to me, ‘I’ve got one big regret in my life. I was so hard, hard on people and hard on my wife and I repent.’ And of course, that was one of the great messages of the East African revival, which George Chambers embraced. And Langford Smith embraced. Neville Langford Smith was very keen member of the East African revival to walk in fellowship and humility being broken before God, walking in fellowship with one another in forgiveness, repenting of your sins to one another.”

Checking the names and places – and there were a lot more names and places – I discovered there is a deep literature on many of these witnesses. What a cloud they were.

(Colin Reed – pictured – is the author of Walking in the Light which draws the links of the East African revival to Australia, Pastors, Partners and Paternalists: African Church Leaders and Western Missionaries in the Anglican Church in Kenya, 1850-1900. and The Tent and the Elephant and other African tales, his autobiography. He is the former principal of St Andrews hall the CMS training instiute in Melbourne.

The title of the talk was, in fact “A Cloud of Witnesses”, but this is not what gave rise to this writer’s appreciation – it was the content that matched the Bible term.)