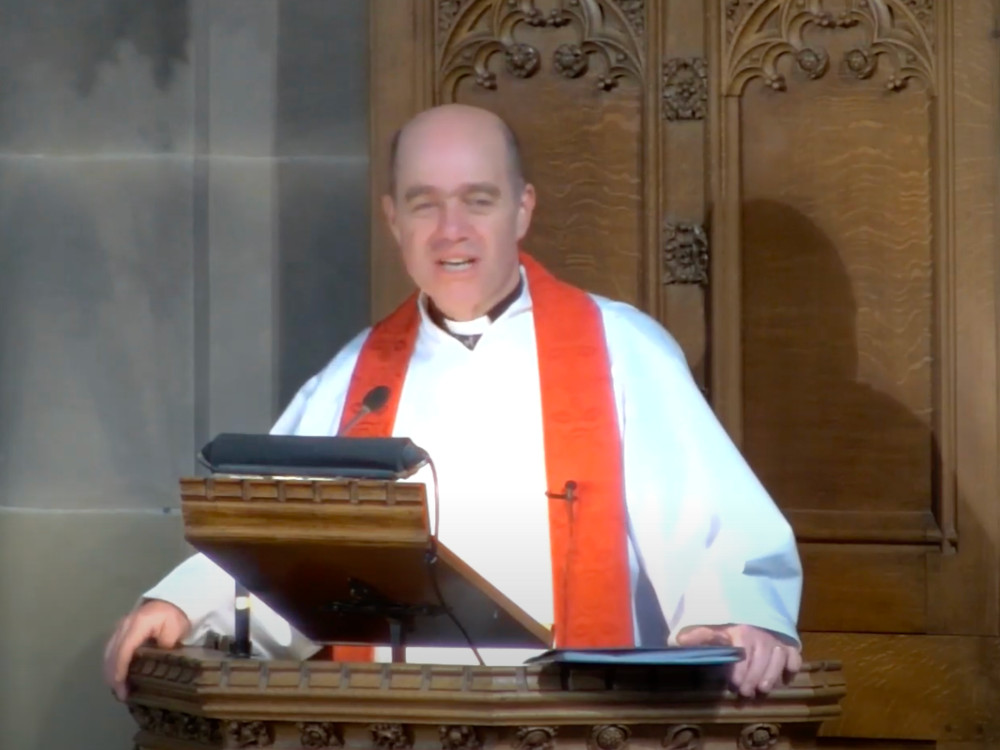

Richard Humphry, Anglican Dean of Hobart’s, sermon on the Indigenous Voice to Parliament makes the case for a sympathetic hearing of the “yes” case. This edited version was published in the Mercury, a video of the sermon is also available – see below.

The Christian Scriptures start with a voice, God calls creation into being with words. Christians believe in a speaking God, a God who has a voice, we don’t have to go discovering things about God, we are to listen to him.

In the New Testament this speaking God comes with greater clarity when at the start of John’s Gospel we hear that in the beginning was the Word, we could say “The Voice”, and this Voice was with God and was God and through this Voice all things were made.

But then this Voice came to speak with us as Jesus became the Word made flesh in which we hear words of grace, love, hope, justice and salvation. Further the death, resurrection and ascension of Jesus are vindication of all that Jesus said and did.

The Jesus who spoke the parables is not the Jesus ruling as potentate at God’s right hand.

Our starting point then should be God has a voice, the question is are we listening?

As we think about the current proposal of a Voice, what in particular of what God has said to us should we be listening to?

We could think of the command to love our neighbour as ourselves. What might loving our neighbour mean as we consider this question? Surely part of love is to listen. This is worth developing further. The God we believe in has a voice, we are made in his image, then our voice is a God given thing. Which means if we are not listening to the voice of the other we are in effect dehumanising them.

This is why the idea of the Voice is of course an evocative one. It is no surprise that “You’re the voice” is such a powerful song, at times our default national anthem, as it carries the idea of not living in fear, not living in silence but being truly heard.

We could consider the Good Samaritan, Jesus’s amazing story which asked his readers to reorder their moral imagination so transcended cultural and religious boundaries to bear the cost of righting wrongs. The good guys were not good, the bad guy wasn’t bad and here we see what it is to love our neighbour, to give of the care of the other and being willing to bear the cost. This is of course the type of love we see in Jesus.

We could think of the biblical idea of reconciliation (Colossians 1:20). If we are followers of Jesus then we should be working for reconciliation and this is certainly something we need in Australia. Working not from a position of power but knowing the transforming and reconciling love of God working with faith, hope and, above all, love to help bring Thy Kingdom Come.

These are all helpful thoughts, particularly in terms of our thinking around Indigenous issues in Australia and would make us better citizens of our community, but does it really help us specifically with the question of the Indigenous Voice to Parliament.

James speaks to those who are comfortably rich by making others poor. “Listen! The wages of the labourers who mowed your fields, which you kept back by fraud, cry out, and the cries of the harvesters have reached the ears of the Lord of hosts.” (5:4).

God hears the cry of those who are defrauded, denied a share of the profits, and deprived of the fruit of the land.

I cannot but help think of our own history of pastoral expansion, particularly the land grab in the southeast of Australia in the 1830s. But it has continued throughout our more recent history. In the far North, we were happy for original owners to keep the land when to European eyes it was agriculturally worthless but with a quick change of mind when we discovered what was under the soil.

Just as Jesus invited the Jews of his day to a radical rethinking in the Good Samaritan, we need to do the same.

We could think about this in relation to our own Cathedral Church. Our history goes back to 1817 when the foundation stone for the first St David’s was laid. We appropriately celebrated the 200th anniversary of that event six years ago. But now imagine you are one of the muwinina people in 1817 looking at a building being erected by people that only 13 years previously had never set foot on this land when your people’s feet had roamed this land for millennia. This is your land but they are putting their building on it. This Cathedral is in muwinina land. Would we not cry out for justice.

Sadly, all too obviously this injustice is not just historical but is a present reality. Being disposed of their land, our Indigenous brothers and sisters have lower life expectancy, higher infant mortality, higher rates of alcohol and other substance abuse, higher rates of domestic violence and they are the most incarcerated people on the planet. This is an injustice and the voice of God says he hears their cries. We are being asked to also hear, to listen to their voice.

This is not then about one group getting more than the rest, but of restoring what has been lost and seeking justice.

People will make their own choices about how to vote but I believe that Christians should start from a position wanting to hear the Voice.

Richard Humphrey is Dean of Hobart at St David’s Cathedral