ANALYSIS Richard Osling via Religion Unplugged

Whatever their partisan preferences, Americans can agree that the coming four years under President Donald Trump will bring major disruptions and contentions in politics. How might that affect religion? In particular, what’s now at stake for evangelical Protestantism, the most important sector of U.S. Christianity in terms of active membership and dynamism — with its millions of Trump voters?

All U.S. religions are coping with ascending secularism, and polls continue to underscore the Democratic Party’s heavy dependence on the growing ranks of non-religious voters, who favoured Kamala Harris by 72 per cent, according to AP VoteCast. Exit polling showed white evangelicals’ customary lopsided Trump support (81 per cent), plus a must-watch Republican trend in the Hispanic population that includes a sizable evangelical minority (meanwhile, exit polling had white Catholics favouring Trump by 60 per cent, and with Hispanics added, Catholics overall gave him 56 per cent support).

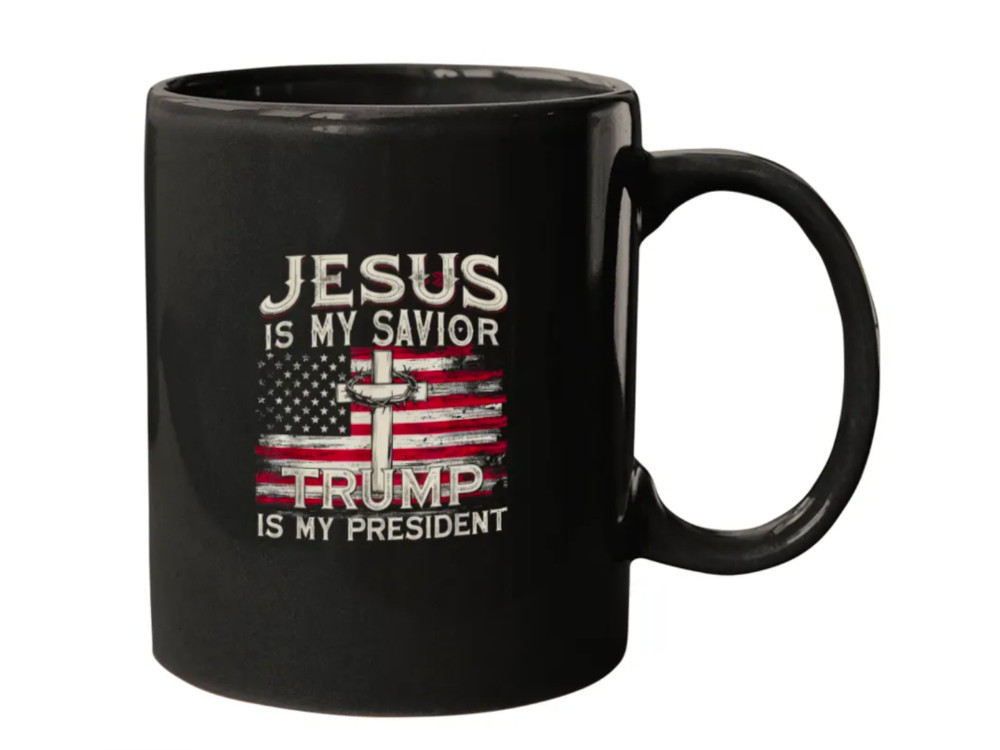

Trump is a “transparently non-evangelical” politician, in the words of Henry Olsen at the conservative Ethics and Public Policy Center. Critics who view him and his policies as morally troubling have produced a mountain of commentary puzzling over that strong evangelical support. An added head-scratcher is that Gallup data gave Trump a lower average approval rating during his first term than President Joe Biden’s to date. In fact, it was lower than with all presidents since World War II.

One explanation is that religious conservatives simply lean conservative politically, and Republican turf expanded when white Democrats’ “solid South” of the long-running Jim Crow era collapsed. Evangelicals’ support for Trump’s three runs was similar to their 79 per cent for Mitt Romney (even though they’re doctrinal opponents of his Latter-day Saints church), 73 per cent for John McCain (despite his swipes against some on the “religious right”) and George W. Bush’s 79 per cent in 2004.

Here’s a key reality that those unfamiliar with the evangelical heritage typically miss, as documented by social scientists and especially those with Duke University’s National Congregations Study. News media emphasis and certain political preachers notwithstanding, evangelicals remain the least politicized sector in American Christianity. Only 43% of local evangelical congregations practised any of the 12 types of political activities in the Duke survey, compared with the more liberal “mainline” Protestants (at 52%), Catholics (81%) and Black Protestants (82%), not to mention the well-known activism of Jewish synagogues and Muslim mosques that were not part of this research.

This reflects a long history in which evangelicalism rejected liberals’ Social Gospel and insisted that churches’ purposes are old-fashioned outreach, persuasion, conversion and discipleship. Spokesmen continually warned about the dangers to Christian influence when the faith appears to be linked with particular parties, candidates and legislation.

This underlies what critics lamented as white evangelical dereliction during the civil rights movement. Some evangelical strategists hope the coming years might gradually erase the image of their Bible-based faith as fused with the Trump phenomenon, though at the moment, this seems most unlikely.

Note that Trump increased his 2020 showing and swept commanding majorities of the states and counties, yet could not reach a symbolic 50 per cent of the nationwide popular vote, posting a mere 1.6 per cent edge over Kamala Harris. That means churches must minister to a national population that’s almost exactly split in two. And both halves are angry.

The split is examined in the 12-page cover story in December’s Atlantic magazine, written before Election Day by New York Times columnist David Brooks. The headline: “How the Ivy League Broke America.” Both Brooks and the magazine are anti-Trump. While evangelicalism is the most populist of faith movements, Brooks decries the power and performance of what has become the elite American “meritocracy.”

Brooks accuses elites of creating “an American caste system” that disdains the value of those who lack college degrees. Unlike the working class, the college-educated population thrived even as the recent cost of living rose, and the deck is stacked in its favour in numerous other ways. College grads control schools and colleges, the news media, entertainment, government bureaucracies, the law and important business sectors. The elitists are largely isolated from, and too often contemptuous toward, the majority of the American people.

In other nations, too, he says, peoples’ attitudes vary by degree of education — “on immigration, gender issues, the role of religion in the public square, national sovereignty, diversity and whether you can rust experts to recommend a vaccine.” In America, the results of all this include two Trump victories and “pervasive cultural and political war.”

The pattern is reflected within U.S. evangelicalism. The movement has always encompassed competing theological strands yet was long a strongly unified force on spiritual and moral basics. But today it is riven by the class divide. Alongside the grass-roots masses drawn to Trump, he gets little enthusiasm from the creative executives and brain trusters who built evangelicalism over the past generation with its vast network of schools, specialized mission agencies, charities, denominations and local ministries.

Writing for Christianity Today, a longtime lead voice of the movement, evangelical historian Daniel K. Williams, notes that only 29 per cent of white evangelicals have college degrees and says the education gap is dividing Christians. Trump’s advent exacerbated this through “strong opposition to the establishment, whether in government, the media or education” that also affects churches.

Upon Trump’s 2016 advent, Williams reports, 81 per cent of white evangelicals with college degrees voted for Trump and likewise, 80 per cent of those without college. By 2020, the percentages of those groups lurched to 63 per cent versus 84 per cent. A 2022 study found evangelicals’ two educational categories differed by 26 points in Trump’s approval ratings. Thus the question: Can evangelicals and their institutions recover the warm unity of yore?

Then this. Katelyn Beaty, who was Christianity Today’s first female managing editor, asserts that pro-Trump churches that are imitating the candidate’s “manosphere” strategy risk significant losses among younger women.

“A Christianity that denigrates women in order to boost up men is a far cry from the teachings and example of Jesus,” she contends.

A prominent evangelical legal activist, C.E.O. Kristen Waggoner at the Alliance Defending Freedom, told The Wall Street Journal last month that “throughout her career as a public official, Kamala Harris has long used government power to try to coerce people of faith to violate their consciences, especially regarding abortion and gender ideology.” Legions of religious voters felt that.

Alarmists on the Left continually warn against a Trump-era “Christian nationalism,” a slippery label. But words like Waggoner’s indicate that in the legal fights of coming years, evangelicalism — and official Catholicism as well — will actually be on the defensive, seeking room for what they believe are legitimate religious rights rather than dreaming of some theocratic political takeover that tramples on followers of other religions, or of no religion.

Editor’s Note: The writer is a lifelong evangelical Protestant, though in varied denominational settings, and the one-time news editor of Christianity Today.

Richard N. Ostling was a longtime religion writer with The Associated Press and with Time magazine, where he produced 23 cover stories, as well as a Time senior correspondent providing field reportage for dozens of major articles. He has interviewed such personalities as Billy Graham, the Dalai Lama, Mother Teresa and Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI); ranking rabbis and Muslim leaders; and authorities on other faiths; as well as numerous ordinary believers. He writes a bi-weekly column for Religion Unplugged.