An open letter from Rev Tim Costello to church leaders on the Voice

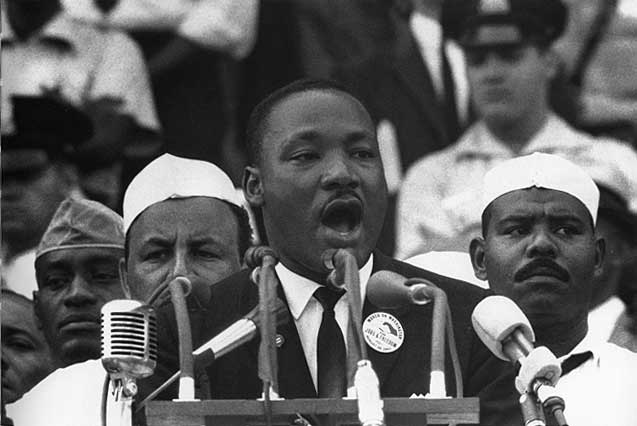

This week marks the 60th anniversary of Martin Luther King’s I Have a Dream speech. Those prophetic words for all Americans are now etched in history.

Less well known, but no less important, is King’s prophetic words to white religious leaders written from Birmingham Jail. It was smuggled out, written around edges of old newspapers and raggedy bits of paper as he was allowed nothing to write on.

He addresses the white clergy who claimed to support the cause of equality but called his direct action “unwise and untimely”. While those clergy leaders urged “patience” and delay, he responded that he had “never yet engaged in a direct action movement that was ‘well timed’ according to the timetable of those who have not suffered unduly from the disease of segregation… We have waited for more than 340 years for our constitutional and God-given rights.”

The letter from Birmingham Jail is as heavy-hearted as his Washington speech is uplifting. To ministers saying ‘Those are social issues, with which the gospel has no real concern,” King revealed a disappointment. It is the pain of a brother and not an enemy: “I do not say this as one of those negative critics who can always find something wrong with the Church. I say this as a Minister of the Gospel who loves the Church, who was nurtured in its bosom, who has been sustained by its spiritual blessings and who will remain true to it as long as the cord of life shall lengthen”.

MLK’s words inspired me years later to become a Baptist minister. I even named one of my sons after him. But there’s something freshly relevant today as he calls out “a completely other worldly religion which makes a strange, un-Biblical distinction between body and soul, between the sacred and the secular”. Among so many of Australia’s church leaders, on the profoundly important issues of Indigenous injustice, we find caution rather than courage. They say these issues are too divisive for church leaders to address. I encounter this argument every day as church leaders close their doors to Indigenous leaders and voices like mine seeking to explain why we are voting Yes in the Voice referendum.

We are voting in a referendum, not a partisan election. This referendum was requested by an overwhelming majority of Indigenous leaders. The current PM has answered that request, and he has the support of many prominent past and present Liberals, including half of Australia’s state conservative leaders. It is a chance for Australians to transcend the tribalism of day-to-day politics.

So let me explain why I believe this goes to the heart of my faith.

As a Christian, I ask the question: What right do we have to oppose what our Indigenous brothers and sisters are asking for? In 1937, William Cooper, a Yorta Yorta Christian leader, secured thousands of Indigenous signatures on a petition to ask King George the VI ‘to prevent the extinction of the Aboriginal race: to secure better living conditions for all; and to afford Aboriginal representation in Parliament. The King never saw it as the PM and States blocked it from even being sent. And where were the Churches then? Sadly over the years, we have gone missing or remained deaf to the pleas of our brothers and sisters.

But that is not how our Christian story began.

From its earliest days, the church has navigated conflict and inequality. Jewish Christians insisted they would not eat with Christian Gentiles until the apostles made it clear that transcending those divisions was at the heart of living out the gospel. They had the courage to overcome resistance, and the message of freedom in Christ and one family in Christ, not two – a Jewish Christian and a Gentile Christian soon carried across the world.

Barely any Australian Christian today imagines they would have opposed William Wilberforce’s fight against slavery had they been alive in his day. But that’s not what history teaches us. Many Christians said Wilberforce’s campaign was political, not spiritual. ‘The Record’, an evangelical newspaper in Wilberforce’s time, labelled his campaign against slavery as divisive and not of the Gospel. They baulked at giving any political expression to the biblical vision of now being “neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free” but united in Christ.

When alive, voices like Wilberforce that challenge inequality are always accused of being divisive and political. The irony is that once they have died, we celebrate them. Why don’t we learn from history? How is it that many can joyfully sing the anti-slave anthem Amazing Grace, then go out and oppose the Voice? Why are leaders not challenging the flood of disinformation from White Christian nationalist websites from the USA?

It’s hard to imagine a stronger connection than that between Wilberforce’s evangelical network in the 1830s and the cause of justice for Indigenous Australians. They made the bold case that Aborigines had been made in God’s image and had rights as those who occupied this land. They established the Aboriginal Protection Society, which exposed colonial injustices. The evangelical Secretary for the Colonies, Lord Glenelg, and the evangelical civil servant James Stephen sought to prevent the takeover of unoccupied lands in South Australia, insisting that unoccupied lands belonged to the Aboriginal people and needed their consent or treaty. Those efforts were circumvented by Robert Torrens and other settlers, who wanted to behave like the other Colonies and just take the land.

The Wilberforce evangelicals had more success in NZ. Why was the Treaty of Waitangi struck in 1840? Because of the strengths of that Christian evangelical vision in Westminster. It would be more than 150 years before native title was recognised as law in Australia in the Mabo case in 1992. Once again there was a massive ‘No’ case scare campaign claiming that Australians would lose our backyards with the Native Title Act. But as sensible voices at the time reassured us, not one centimetre was lost.

Like MLK, we can be both proud of our many national achievements, as well as be honest about injustices that date back to our foundations. Captain Cook, in 1770 claimed all of the land on the Eastern continent of Australia for the British King on the basis of the legal principle of discovery. In the same year, America’s second President, John Adams, wrote in the Massachusetts Gazette that this principle clearly “could give not title to the English King by common law, or by the law of nature, to the lands, tenements, and hereditaments of the native Indians.”

When Australia’s constitution was being written, the language of natural rights – so familiar to Wilberforce’s network – had sharply declined. The only delegate to raise questions about the fate of Aboriginal Australians was Sir William Russell, the delegate from New Zealand – a country that by then had fifty years’ experience of a treaty with Indigenous inhabitants. Russell warned that the new federal Parliament “would be a body that cares nothing and knows nothing about native administration.” Cautious voices told him not to worry because Australia’s Aborigines were dying out, as if the fate of Indigenous peoples could be attributed to natural causes. And so Aborigines were left out of our Constitution – the injustice that we are now addressing – while special provision was made in our Constitution for the future inclusion of New Zealand.

I fully accept that voting ‘No’ does not mean you are a racist. But I’m sure there are not too many racists voting ‘Yes’.

Enough of the discredited line that to stand up to injustice is divisive, dangerous and unwise. Four in five Indigenous Australians are asking for a voice, and Christians represent a larger share of the Indigenous population than the population at large. Let’s heed the lessons of history from Botany Bay to Uluru. Let’s raise our voices for Amazing Grace, but let’s not fail the true test for our generation.

Rev Tim Costello is the former President of the Baptist Union of Australia and a former Tearfund Board Member. Used with permission.