An office email sent Jonathan Harris on a quest to uncover how his grandmother had translated the New Testament into an indigenous language. In seeking to know the past, he learned how to truly be a Christian. His story comes from the new book Footsteps for Future Generations, published by Youthworks Media

It was 2018, and I had been working for Bible Society Australia for a year. I was 53 years old, and I wanted to ‘make a difference’. One day, Louise Sherman, our Remote Indigenous Missions Support Coordinator, shared a message with the staff that would change my life. She reported:

Received the printer proofs and sample cover for the Kunwinjku New Testament from Amity Press in China. Planning for the dedication later in the year in Oenpelli (Gunbalanya) in west Arnhem Land. It should be an amazing celebration. Congratulations to Steve and Narelle Etherington and CMS [Church Missionary Society] and, of course, to the amazing local Kunwinjku translators who have been working on this for over ten years.

A quick comment came shortly after from Rev Dr John Harris (no relation), Bible Society’s Heritage Translation Consultant, [best known for his book One Blood, 200 Years of Aboriginal Encounter with Christianity] explaining:

The first translation of any part of the Bible into Kunwinjku was St Mark’s Gospel, translated by Jonathan’s grandmother, Nell Harris, and the women of Oenpelli. In the diary of Jonathan’s grandfather, Dick Harris, there is a breathtaking entry: ‘Christmas 1936: We read the lessons in our Church Services in Kunwinjku for the first time ever.’ Dick did not know it, but I believe this to have been the first time ever that the Gospel was read in an Aboriginal language in any Anglican Church in Australia. We have a few copies in the library.

This rocked my world. I had no memory of this translation work that my grandmother, Nell Harris, had started. My brothers and sister, and I had been too young and uninterested in what our grandparents had been involved in to really care. I quickly called my father, Wilfred Harris, who still lived on our family farm, and asked him about the translation work and if there were any records of his parent’s life in the Territory still available for me to have a look at. Dad simply said, “Sure; they’re all out in the shed.”…

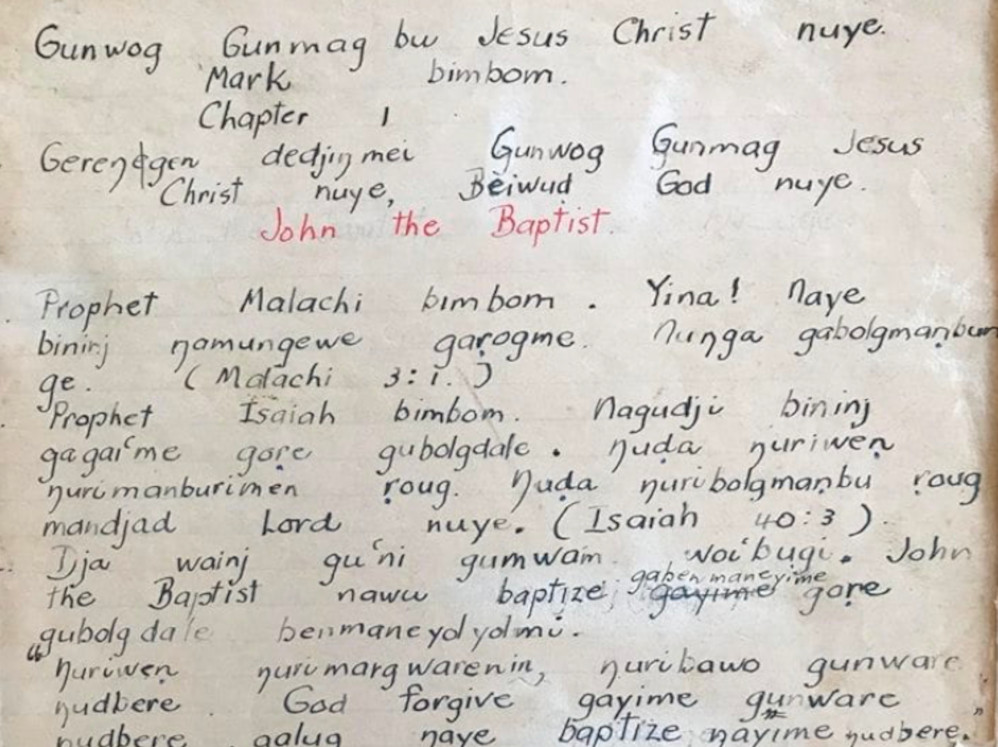

My half-sister Ellen and I travelled back to the farm to look for the records of our grandparents’ time in the Territory. We found three suitcases and the original wooden chest that Grandad had first travelled with, all stuffed with correspondence written throughout their lives. Love letters; artefacts such as clerical collars; Mission blueprints; letters to best friends and family; Mission reports; original journals; letters to friends in The British and Foreign Bible Society; Aboriginal family tree records of the first inhabitants of the Missions; and … original handwritten pre-war exercise books with the phonetic translation of the beginnings of the Gospel of Mark into the local language Kunwinjku.

Further down the pile of papers and letters, I found a tiny volume of the first printed Gospel of Mark and 1 John in Kunwunjku. I opened it to find that it had been published in 1942 by the British and Foreign Bible Society in Sydney. This was the first edition of what would become the complete Kunwinjku New Testament published by the Bible Society through Amity Press in China.

In her published memoir, The Field Has Its Flowers, Grandma wrote about being frustrated about being unable to communicate the Gospels’ heart to Kunwunjku speakers. So she sat with Rachel Guril Naboronggelmak and Hannah Maralngurra, two very intelligent women who spoke the best English, under the shade of a bark hut (the site of the Anglican church there ow), and listened to them in language and began to write down the Gospel. The goal was to do five verses a day. The result was that tiny 1942 book.

The documents make for fascinating reading, highlighting the clash of cultures and the evangelistic mandate of missionaries trying to spiritually save the original inhabitants—and help them survive the invasion of the Europeans. Grandad and Grandma witnessed police retribution in the case of the Caledon Bay massacres, where Aboriginals had speared Japanese and white men. They witnessed firsthand the devastation of the people from European diseases. They recorded the battles they had with the Mission oversight groups and the government, who wanted them to approve payment of tobacco to the locals as was the custom on other Aboriginal reserves. (Dick Harris later resigned from CMS owing to his opposition to the distribution of tobacco as payment for work. The Government threatened CMS that they would cut Mission funding if tobacco distribution were not carried out.) There were also cultural issues that had never been faced before. These included Aboriginal mission children being taken as child brides and spear-throwing retribution justice by local tribes.

After going through the treasure trove and finding the original Kunwinjku translation and the first-edition Bible Society Gospel of Mark, I asked the Bible Society executive team to help me film the journey and personal delivery of the completed ‘Shorter Bible’ (complete New Testament and several Old Testament books) that had just arrived in Sydney from China. I hoped to honour the years of translation work done by so many since Nell, Rachel, and Hannah began in the 1930s. They loved the idea, and a cameraman was sent with me. He visited our farm and filmed my father speaking about Grandma and her work. Dad died a short time after this, and I will always be grateful that he could be recorded honouring his mother, whom he had always thought wasn’t given enough recognition for the work she did

.

A short documentary with the interview is online.

Jonathan Harris recounts his life in the NT with missionary parents and going to live with his grandparents after his parents separated.

We all tended to put my grandparents, Dick and Nell, on a pedestal. They were CMS legends and pioneers. It was hard on them, having to raise us terrible teens who wanted to chase girls and have an 80s-style social life! You would think they deserved a rest. But instead, it was scones, lamb’s fry, sheep carcasses, hand-milled porridge, milking cows and homemade butter and cream. It was twice-a-day prayers, Bible passage reading and hymn singing from the Golden Bells hymnal. It was visiting farm neighbours to discuss Christianity and give out Daily Bread Scripture reading notes. It was Grandad preaching in the local parish. Their foundation was a solid faith in Christ through good times and bad. Their example of sticking to convictions without being pushy moulded my conscience.

But it was also hard on us living without a mother and with ‘old school’ grandparents.

After leaving the farm in my late teens, I went on a year-long trip around Asia to visit missionaries in Pakistan, Borneo, India and Nepal. The last thing Grandad said to me before I left was, ‘Keep yourself clean, boy’. I enjoyed being away from the authorities in my life. When I returned to the farm, Grandad’s dementia had set in, and he was asleep for much of the time. On my final day of that visit, I went into his bedroom and knelt on the floor next to him. I said, ‘I love you, Grandad’—the first time I had said it out loud. I still visit his gravesite in Barraba.

After my ‘missionary trip’, I returned to chase girls, ‘live life to the full’ in college and attempt an acting career. I went dramatically off the rails. I had an idea of religion but didn’t know what being a disciple of Jesus was. My heart wasn’t transformed, and I hadn’t repented. In spite of this, drinking countless bottles of beer and dating assorted girlfriends, my conscience wasn’t clear.

One day, a bloke met me on the street and invited me to a Bible discussion group. I replied, ‘I’m fine, mate. I know all about the Bible. I’ve been raised by missionaries’. After this friend persevered, invited me for meals and showed me love and hospitality—and because of all the prayers that Gran and Grandad had prayed—the Holy Spirit worked on my conscience. I thought, ‘If I don’t repent now, I might never have this chance again’. I delved into the Bible and was baptised a week later.

Since unearthing the archive of documents and artefacts and then watching my father and mother pass away from cancer, I have begun a journey of identifying my own purpose in life.

Sometimes, I’m tempted to try and leave a legacy by writing a meaningful book or achieving a major physical feat that will be remembered. But I try instead to remember the encouragement of one of my favourite Christian thinkers, the late Timothy Keller, to think carefully about our attitude to our legacy, our ‘works’. He explained that striving to leave our mark or be successful in our own endeavours is, essentially, a sin. Idolatry! All God requires us to do is to have faith in Christ’s atoning

his Son. All the effort of trying to leave a heritage or build an investment portfolio, wanting to be remembered for being a missionary or for my good works, is approaching as the older brother in the story of the prodigal son did: ‘Look! All these years I’ve been slaving for you … yet you never gave me even a young goat’ (Luke 15:29). We’re trusting in our own works, not in God’s grace.

Discovering Grandma’s story, even though she passed away a long time ago, has left me with a feeling of pride that she and Grandad had done things according to their convictions and not for human recognition. They made decisions out of very simple faith and managed Missions out of necessity, not out of ambition, pride or a desire to make a name for themselves.

So, I have been assessing my own drive, dreams and impact on the world, starting with my family and then my church and neighbourhood. Much of my thinking has been around how to maximise my limited time left on the planet and how my finances might benefit God’s plan. With so many charities around, it has been a challenge to decide where to give my money, time, thoughts, prayers and work hours.

Footsteps for Future Generations: The Faith Legacy Grandparents Leave, edited by Ian Barnett, Youthworks Media 2023, is available from Youthworks Media for $21.95

Find out more about the kunwinjku scriptures at https://aboriginalbibles.org.au/kunwinjku/

Image: Nell Harris’ translation notes for the first chapter of Mark.