Two different ways of thinking about the “natural state” of Humankind: the ideas of philosophers Thomas Hobbes (who described life as “Nasty, brutish and short”) and Jean-Jacques Rousseau (who asserted humanity is naturally good) were the frame for Christopher Watkin’s first of the 2023 New College lectures last night. Watkin, the author of this year’s Australian Christian book of the year, Biblical Critical Theory, encouraged his audience to think about the origins of how they think about fellow human beings.

This observer’s mind goes back a few days to the South Australian MP James Stevens being asked on the ABC Q and A program if he agreed with Senator Jacinta Price that there were no ongoing negative impacts of colonisation.

“I think European colonisation has been an overwhelmingly good thing for the great society that we live in,” he replied ” “I’m a proud Australian. I’m a very proud Australian. I’m proud of our Indigenous culture. I’m proud of the English institutions that came to this country with colonisation. I’m proud of the multicultural community that we have. I’m very proud of this country, and I think Jacinta Price is a great Australian, and she’s very entitled to put her views forward.”

Rousseauians would disagree. Watkin describes, “One recent bestseller that takes an overtly Rousseauian view is by Brad Aronson, and the title of his book is Humankind. You see how it’s a play on words. So he’s suggesting that we are basically nice people, and at one point, he [says] this is about the curse of civilization that has twisted our noble instincts. And he says things started going on between 15,000 and 10,000 years ago, and it’s all been sort of downhill since. I sort of presented it in a jocular way, but there is a body of recent work, and that is not the only one. There’s … James C. Scott from Yale, I think, [He is Sterling Professor of Political Science at Yale] and others, who are saying that “look actually a hunter-gatherer lifestyle is a lot healthier than our lifestyle and there’s a lot more leisure time”, and we are naive simply to dismiss it and say, “oh, how thankful we are not living in that way anymore.”

Placing Watkin’s thoughts next to the Q and A voice debate, Watkin’s point about the need for us to examine the origins of our views on Humankind is instantly in sharp relief.

“It’s very different ways of inhabiting the world, isn’t it? Treating people in a Hobbesian manner, and treating people in a Rouseean manner is very, very different. And so you’ve got these modern-day Hobbesians and the modern-day Roussouans who are propagating and seeking to build policy around very different ideas of human nature. You’ve also – this is really important – got a third group which are people who deny the validity of these big stories of humanity altogether. So it’s not that the state of nature was all full in society as rescued us.”

A third group describes a more complex idea of hunter-gatherer societies interacting with settlements but still portrays an overarching story. And finally, Michel Foucault, whose position described by Watkin is of “different moments in history that are juxtaposed with one another. But we can’t say that we are better than a previous age. We can’t say that we are worse because every age brings its own criteria of measurement.”

Then, as a Christian, Watkin turns to the Bible. “I think one thing that Christians who have written about as would want to say is that there seems at least trying to face it to be something in each of these stories. Actually, it is the case historically that human beings can be really nasty to each other, not just strategically nasty but gratuitously nasty. Like nasty for no reason other than being nasty. And so the Hobbesian vision of life does, in certain moments, seem to have a really terrible ring of truth to it. But it is also the case that humans can be just inexplicably lovely to each other as well. Not lovely for you sort of evolutionary reasons of preserving the gene pool, but lovely to people they’ve never met who’ve got no common interest with them, but just lovely in a self-giving way, in a way that Rousseau would predispose us to expect.

And it would be hard to suggest that that never happens. Also it will be hard, I think to suggest in the Bible that the whole of history is this wonderfully mapped-out sort of progress from a lower state to some sort of higher state. But I think that what we’re taught to expect in the New Testament is it’s going to be messy. There’s no pure line of travel from where we are to how things will end. There’s a messiness there. And so you can see that each of these stories seems to be resonating with something in the world and with some things that the Bible presents to us. But I think the problem for the Christian, or rather the problem for all these positions that are highlighted by the Christian, is that none of them seem able to account for the whole of human experience.”

Watkin outlined how the beauty and complexity of the Bible account offer a more complete explanation of the state of humanity.

“Genesis chapter one is different to Genesis chapter three, but it is a fact that has huge implications… In Genesis chapter one, human beings are created good in the image of God and are pronounced very good. And then it is only later that sin enters the world, and Adam and Eve turn away from God and the sort of corruption in their relationships, in the alienation, in their relationship sense. And so what you’ve got in the Bible is an origin of good that is separated radically separated from the origin of evil and an origin of evil that doesn’t utterly negate all the good.

So after Genesis three, we don’t wind the clock back to how things were before the creation of the world.

“Evil doesn’t destroy everything; it is in C. S. Lewis’s language that the world ‘has the air of a good thing, spoiled.’ Sin messes things up, but it doesn’t completely destroy all the goodness of creation.

“And that’s what we mean by this asymmetry; that the good precedes and exceeds [evil]. And if we read through to the end of the Bible, we’d see succeeds and outlasts evil as well. And that’s a really quite unusual position to have certainly in the modern world because it means that the Bible has what we might call a multi-lens anthropology.”

Both Rousseau and Hobbes have a home in the Bible, Rousseau in Genesis 1. Hobbes in the Cain and Abel story. The Bible, Watkin says, offers the best way to address human reality.

“What the Bible offers is this double-lensed approach so that the Christian is able to account in her view of the world for the ruptured, unprovoked, depraved actions of people in history. They will bring a tear to her eyes, but they don’t rock her view of the world. But people are capable of really vile things. Sadly, that is who we are. That is who I’m, that’s who you are. But also the Christian will be able to account in her view of the world for the wonderful self-giving sort, non-self-interested acts of kindness of which human beings are capable wonderfully, thankfully.”

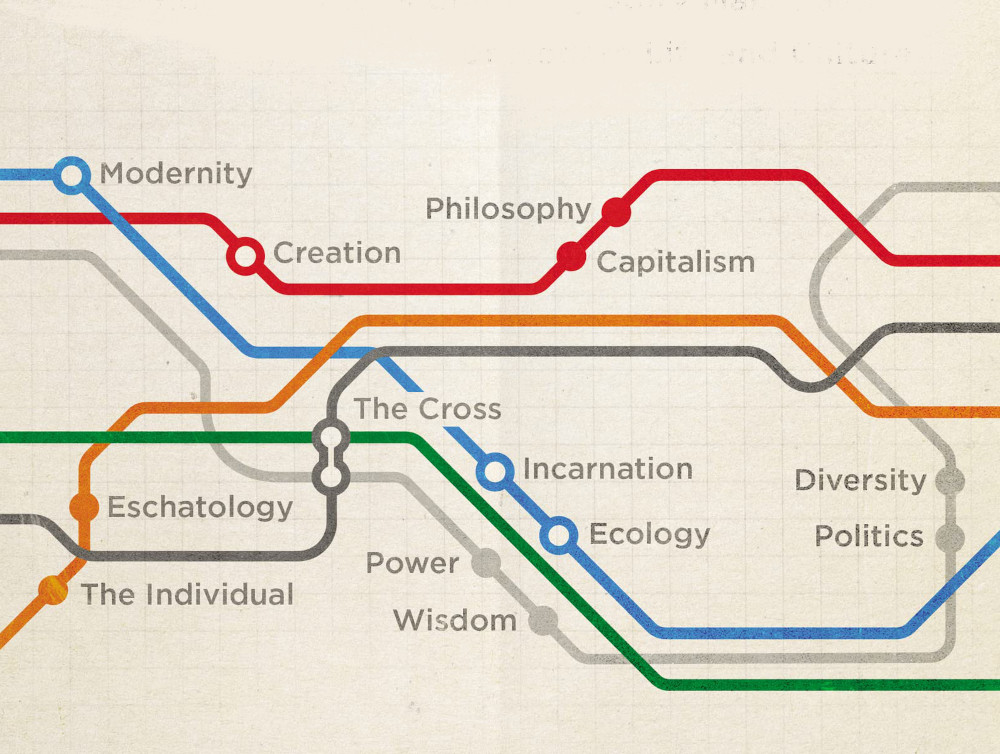

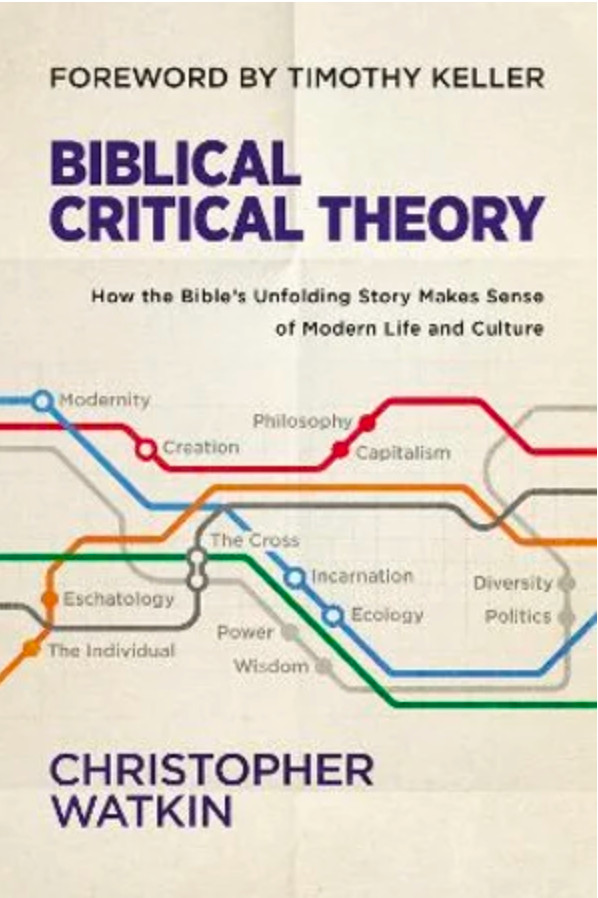

Biblical Critical Theory: How the Bible’s Unfolding Story Makes Sense of Modern Life and Culture by Chris Watkin is available from the Wandering Bookseller and other bookstores.