Actor and author Anna McGahan has won Australia’s most prestigious literary prize, the Vogel for 2023, for a novel. What has that to do with Christianity?

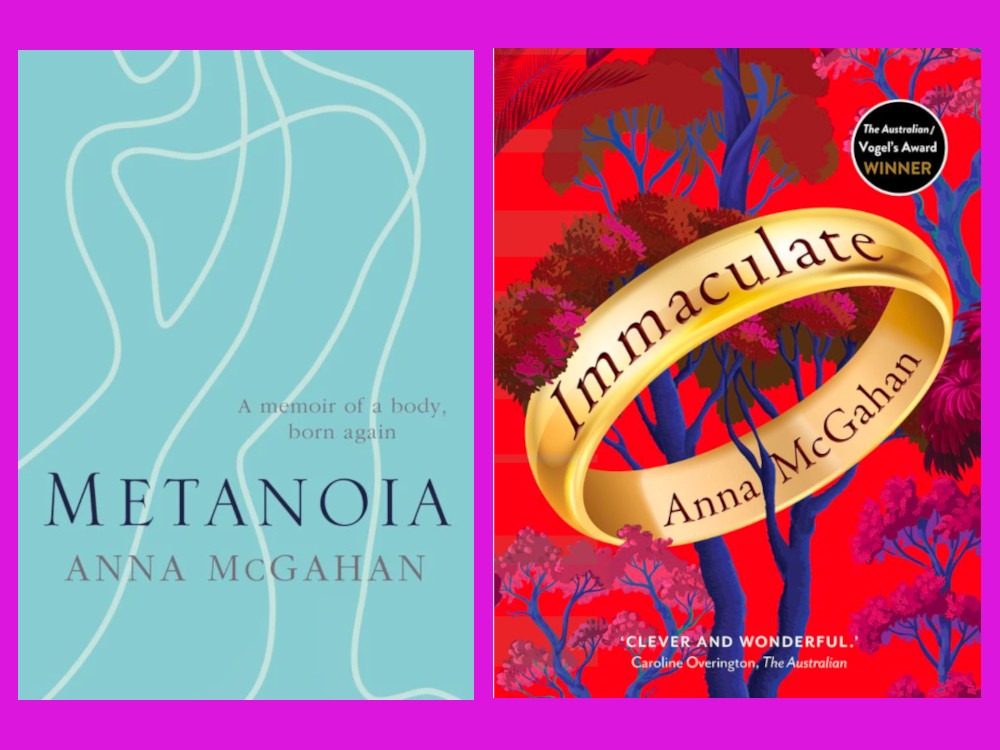

Her prizewinning novel, Immaculate, is set in Brisbane, dealing with a young woman’s experience in a Pentecostal church. But back in 2019, I managed a publishing team at the Bible Society that published her first book Metanoia, a memoir of a young woman exploring and accepting faith – Anna McGahan’s own story. Metanoia is missing from media coverage of McGahan as Vogel winner and maybe that’s a good thing, you be the judge.

“Immaculate is set in Brisbane,” James Ley writes in the Nine papers’ report of the Vogel Award. “It is predominantly narrated by Frances, a convert to and then apostate from an evangelical faith-healing church called (somewhat diabolically) Eternal Fire. Her embrace and rejection of the church coincided with her marriage and separation from a chauvinistic pastor named Lucas. The trigger for their break-up was a crisis of faith Frances experienced when their young daughter, Neve, received a terminal cancer diagnosis.”

Metanoia is mainly set in Melbourne. Written in Anna’s voice, it tells her story of coming to faith, learning to live as a Christian and being baptised. Rather than one main male character, there are two, a young pastor and later “a man who had barely even dated” who Anna married. The crisis in the first book is McGahan’s experience of her nudity on national TV, playing a prostitute. She recounts people watching her, not hearing what she is saying. Metanoia deals with being more than a body.

Metanoia is a delightfully well-written book. It’s quite complex. But it may not have been quite complex enough. There’s a convincing story there. But as someone put to me recently, “Anna McGahan no longer identifies as a Christian.”

That is probably a good way of saying it. It is likely God has not finished with her. We could go on to debate whether “once saved always saved” holds true, but this is meant as an apologia for publishing only half of her story.

This week Anna went to the Australia’s public confessional, the ABC Conversations radio program and took her story forward. It serves to heighten the parallels between Metanoia and Immaculate.

“I knew I was queer, McGahan tells the ABC’s Sarah Kanowski. “I knew that I was free to explore those parts of me, but I’d also, you know, been presented through a very male gaze, I suppose. And was only getting auditions for roles that really expressed a highly sexualized, feminized, um, heterosexual kind of idea of a woman. And was very, I suppose, struck by the different expectations there were on me. And I felt very political and strongly about it, and so much so, in fact, that I was very, very vocally anti-Christian. And I think that’s almost what set me up to fail here (laughs) because I was so like vehemently anti-Christian in my pro-queerness to protect my queerness in a way that when I met, I met a Christian man who was very intelligent and very, kind of like beautiful and provocative and creative and articulate.”

She felt a “surge of, of loyalty and connection” to Jesus. And reading the Bible “I felt this kind of reverence and humility because I was reading things I had never heard, things like, your body is a temple, you are the light of the world.” It was balm for a woman with an eating disorder history, subjected to a male gaze. Of her Christian experiences, “All of these things struck me as not only very beautiful, but very possible because the people that had experienced them were so sure. And I began to experience kind of some of them too.”

But the Pentecostal pastor who Anna began to date turns out to have struggles of his own. He was gay.

In LA, still pursuing Christianity and maybe a little madly, Anna marries another man quickly, despite knowing they were not suited to each other. “it was my own weird rebellion where the more people said to me, you don’t know what you’re doing, the more I almost dug in my heels and said, maybe, but it’s my choice to make. And it’s nobody’s else’s fault in that I think we, I have learned so much from that decision and I have two beautiful children from that decision.” A choice to marry.

In Metanoia, that relationship is presented as an idyll. But that was not how it turned out.

McGahan’s reflection on what marriage meant in a Christian community is instructive. On having her first child, “I think it shifted for me this idea of where my feminism could sit in Christianity because the way that I was treated as a woman changed when I got married, the way that I understood my femininity and my agency changed.

“You get legitimacy in a social standing when you get married, but you also become below someone in particular. You are no longer yours. You become your husband’s. You become somebody that is intended to be a mother and a helper, not a leader in your own right. And even if churches don’t actively subscribe to that thinking, it’s in the Bible and they have embodied it. And I felt so fierce and alive when I became a mother that all of a sudden this anger began to grow towards the general idea, not, not not just my partner who who was genuinely trying, I just sat in this space of going, I’ve just had daughters. Am I going to let them inherit this? Absolutely not.”

Neither the reader of this piece nor I, were there in this US Church. It may be that others saw things differently. But McGahan’s description is on the face of it, not unlikely.

The neatest way to wrap this reflection would be to point to the parable of the seeds and conclude that maybe this was hard or thorny ground.

But if that is so, some of the thorns are Christian. The pastor and the husband contribute mightily. Perhaps they create her crisis of faith? And publishing Metanoia, though genuinely felt at the time, did not help.