The headline quote comes from Jeff Walton – no lefty he, as he works for the conservative religious thinktank the Institute for Religion and Democracy (IRD) – as he responds to a brouhaha about UK controversialist priest Calvin Robinson at a US conference called Mere Anglicanism.

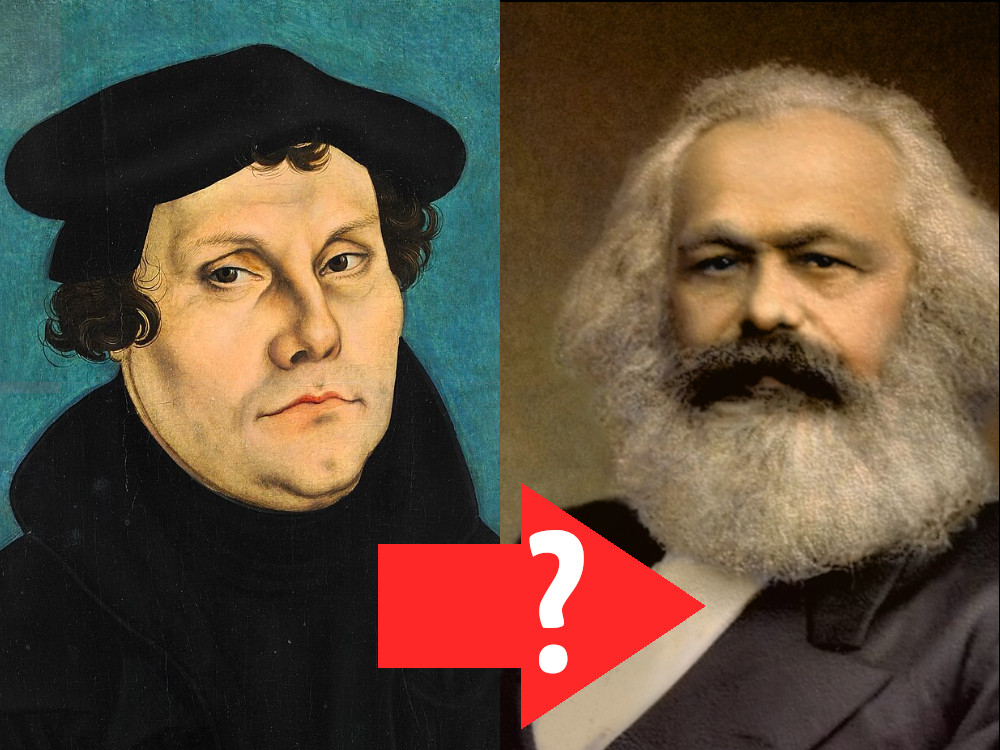

‘Drawing a straight line from Martin Luther to drag queen story hour’ was Walton’s exaggerated way of referring to Calvin Robinson’s interesting argument linking the Reformation to the (eventual) rise of intersectional modernism.

Or as Robinson puts it in his substack entry about the conference, “Feminism is a tool of entryism for the Critical Theories. Women’s orders, in particular, confuse our understanding of men roles and women’s roles and our place in creation, and Marx’s manipulations of Luther’s work are an attack on God.” Indeed, many progressives would agree – the argument is that admission of women to the priesthood must lead to ordaining LGBTQIA people as well.

Robinson’s comments against women priests caused the blow-up rather than his comments about Marx or Luther – the conference is sponsored by a church in the Anglican Church of North America, which is decidedly split on the question. As Walton said in an interview on the Anglican Unscripted podcast, Robinson rolled a hand grenade down the aisle. Consequently, Robinson was disinvited from participating in a concluding panel—a storm in a teacup in South Carolina.

But the Marx/Luther question is interesting – as it suggests two Christian approaches to how we relate to society – a traditionalist authoritarianism (reflected in the era of Kings and empires aligned to the church) and a classical liberalism that allows for a diversity of opinion.

In a critical part of his talk (after the hand grenade had gone off), Robinson gets to Karl Marx.

“Let us take a look at what Marx says himself. In his Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right in 1884, Marx beings with, ‘For Germany, the criticism of religion has been essentially completed, and the criticism of religion is the prerequisite of all criticism.’ but it is not a criticism of religion he is interested in, not really. It is a criticism of God, the God of the Bible, ‘Man, who has found only the reflection of himself in the fantastic reality of heaven, where he sought a superman, will no longer feel disposed to find the mere appearance of himself, the non-man [“Unmensch”], where he seeks and must seek his true reality.’”

Marx dethones God. For Marx, liberation from God is needed to set humankind on the path to liberation. At the next point, Calvin Robinson appears to agree with Marx’s next point that Luther was his ally.

“In his call for a revolution, Marx states, ‘Germany’s revolutionary past is theoretical, it is the Reformation. As the revolution then began in the brain of the monk, so now it begins in the brain of the philosopher.’”’ putting himself forward as the leader of this revolution of secularisation. To finish the job his brethren Luther began. And he means this: he gives Luther credit where he believes it is due, ‘Luther, we grant, overcame bondage out of devotion by replacing it with bondage out of conviction. He shattered faith in authority because he restored the authority of faith. He turned priests into laymen because he turned laymen into priests. He freed man from outer religiosity because he made religiosity the inner man. He freed the body from chains because he enchained the heart.’

Calvin Robinson also credits (or discredits) Luther with this change.

“Here, we see liberalism at its peak. When Marx says Luther shattered faith in authority because he restored the authority of faith, could it be that he is saying in destroying the people’s faith in the Church, people put their faith in their own consciences. In removing the authority of the Church Universal, magisterium, papacy, et al. people granted themselves authority and therefore made Marx’s job of crushing Christianity all the more easier. He no longer had to battle with a universal Truth; he only had to challenge the subjective perspective of truth.”

Here, Calvin Robinson’s Anglo-Catholicism comes into play. The church in charge of society is the ideal. A church based on the convictions of individuals, rather than the imposed power of a kingly state, opens the way to liberalism, which he opposes in favour of a more authoritarian society.

Here, we need to decide what sort of liberalism we are talking about. The classical liberalism of the freedom of assembly, thought, politics and the free market, or the neoliberal modernism of the present.

Some of classical liberalism, especially freedom of thought, comes from the reformation. But contra Calvin Robinson (but not Marx), the downfall of stately power, not directly due to the Reformation, gave rise to classical liberalism. The Enlightenment drove things further.

But the religious freedoms unleashed by the Reformation (eventually) are surely worth cherishing. Would a Christian state still grant those freedoms? Or would it drift back to a magisterium and coercion?

Because a Christian state seems so unlikely, it appears to be an academic question. Perhaps not so academic if we take Putin’s Russia and Orban’s Hungary as examples. But the question bears on Anglicans in particular – remembering that the conference that Robinson was at was called “Mere Anglicanism.”

One might map what I have described as classical liberal versus authoritarian ideals onto a schema by The New York Times’s Tom Friedman in a recent column, “On one side is the Resistance Network, dedicated to preserving closed, autocratic systems where the past buries the future. On the other side is the Inclusion Network, trying to forge more open, connected, pluralizing systems where the future buries the past.”

Friedman puts Russia into the authoritarian Resistance Network, and Ukraine which is trying to break away into the Inclusion Network. And here’s how he sees Gaza: “Israel was trying to forge a normalized relationship with Saudi Arabia, which is the gateway to the many Arab Middle East states and Muslim states in South Asia with whom Israel still does not have relations. But it’s not only Israelis who wanted to see El Al planes and Israeli technologists landing in Riyadh. Saudi Arabia, under Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, itself aspires to become a giant hub of economic relations that would tie Asia, Africa, Europe, the Arab world — and Israel — into a network centred in Saudi Arabia. His vision is a kind of European Union of the Middle East, with Saudi Arabia playing the anchor the way Germany does with the real E.U.

“Iran and Hamas want to stop this for joint and separate reasons.”

The word “inclusion” is sometimes used as a code for a progressive agenda for churches, but in this piece, we will confine it to describe general society. Robinson and others may well argue that it is wrong to separate a view of what should happen in the church from society in general. (This takes us back to Martin Luther and his idea of two kingdoms, the church and the state. How closely they should support each other’s views and whether the state should be bound to the church’s position has been a lively debate in 500 years of Lutheran history. (A paper on this history by Francis Fukuyama is here.)

Some of the most significant Anglican provinces criminalise same-sex sexual activity with lengthy prison sentences supported by the large Anglican churches in these countries. (The death penalty added in the recent Ugandan legislation was opposed by the church of Uganda, and the death penalty in Nigeria applies in the Northern states with sharia law.)

To what extent do Christians want to live alongside those we disagree with? Put bluntly, do we still want to jail LGBTQIA people? If the answer is “no,” we are stepping into the inclusion side of Friedman’s schema, while still maintaining our views and doctrine.

The erosion of Christian influence in Western societies has led to a Christian stance that is simply opposing change.

There is a need for Christians to have a positive vision of where we sit in society. This is not to disparage campaigns for Christian schools to have the ability to staff themselves with Christians, for example – but the history of many campaigns can be seen as strategic retreats rather than a political vision of the place of a Christian minority in society.

The long history of Christian privilege has shaped our attitudes – and makes appeals for us to have authority or to restore our authority in society seem plausible. But another model is found in 1 Peter, a book written to a minority Christian presence within an empire: “To God’s elect, exiles scattered throughout the provinces of Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia and Bithynia… (I Peter1:1).

They are to “Live such good lives among the pagans that, though they accuse you of doing wrong, they may see your good deeds and glorify God..” (2:12), obey the human authorities (2:13), yet “Always be prepared to give an answer to everyone who asks you to give the reason for the hope that you have. But do this with gentleness and respect, keeping a clear conscience, so that those who speak maliciously against your good behavior in Christ may be ashamed of their slander.”(3:15–16). To be fair, Calvin Robinson sees Christians living as remnants in Western societies.

Much Christian campaigning proceeds as though there is still a Christian majority. The last few weeks of the Morrison Government and its grappling with religious discrimination law can be regarded as policy on the run, not only by the government but also by Christians negotiating with it.

It may be that the exile of Christians today in Western society will last for some time. But for those Christians who aspire to state power, please consider this saying: “Jesus called them together and said, ‘You know that the rulers of the Gentiles Lord it over them, and their high officials exercise authority over them.’”

Matthew 20:25 NIV

Image: Luther by Lucas Cranach the Elder, Karl Marx colourised by Artistosteles, both via Wikimedia