From Hobart

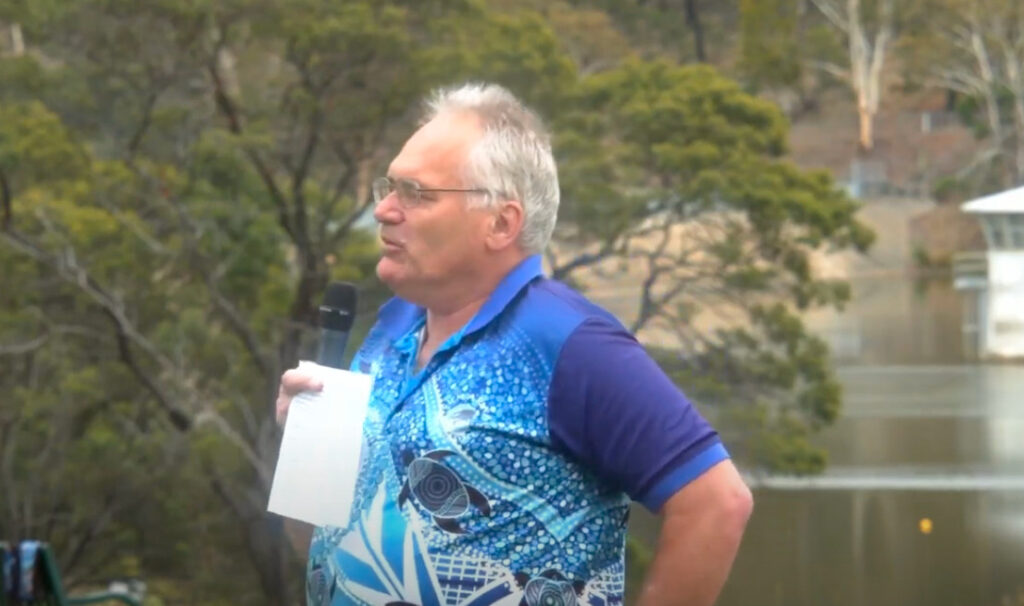

Citywide Baptist, a multisite church in Hobart, headed to Risdon Dam for their Aboriginal Sunday Service and heard from Pastor Paul Dare, a proud indigenous Lia Pootah man.

So, who everyone’s been to Sydney? Gadigal country. I take it. Who hasn’t been to Sydney? Oh right, good. Okay. So Pitt and Castlereagh Street, everyone knows Pitt Street Mall. Yep. Okay.

There’s a monument there. And the monument there is actually a monument to the first sermon preached in Australia. I did not know that until I did this. I did not know that. And on the monument, it’s got the first verse ever preached in Australia. And the verse is Psalm 116 verse 12: What shall I render unto the Lord for all his benefits to me? And when Safina [Stewart – one of the authors of Common Grace material for Aboriginal Sunday that Dare references] went there, she found this thing, she found the verse, she found the monument, and she wrote this.

“All of a sudden, I started listening from the floor up from my feet up. And what I noticed around me was all of this hustle and bustle, all of the business, pedestrians, all these huge buildings,

And they grieved because the land had been covered, completely covered by cement and paved over. You cannot see the land in that point anymore. But I could hear it screaming, and I could hear it within my spirit, the voices of ancestors who had not received peace from justice and right relationship. I could feel them coming all the way through, and I could hear them through my feet.”

And why you might not agree exactly with the sentiment he expressed in it, there is such a thing as connection to country and standing in the dirt. There’s gardeners who tell you, there’s people who tell you if you go stand in the dirt, you’ll become more well-grounded. And for the Aboriginal people, it’s a really, really strong belief. When you’re on country, you stand in dirt.

I remember this girl, she was about 12, and she had an open heart surgery in Brisbane. She came from Mount Isa, and all she wanted to do was get back to her home country and eat dirt just to feel that connection again. And so you’ve got this person here, and they just need to feel a connection, but they can’t because it’s been scarred, it’s been covered over.

And that’s what it’s like to be an indigenous person. You’ve got this history that you want to be able to experience in peace, and they let others understand it, but you can’t because it’s been covered over. It’s been covered up for 200 years. … If you look out here now, and if you just imagine out here 240 years ago what that would’ve been like looking out there, no dam, this hill would’ve been here, and you would’ve just been sat looking out and seeing nature, seeing God’s creation at its finest.

You would’ve been in awe at the quietness, the stillness, but also the hustle and bustle of the undergrowth, the kangaroos, the emus as they were then, the echidna. All those animals are unique. They would’ve been roaming around here and people living a subsistence lifestyle, but they were still living. And then to have it all change within that period of time.

Oh, a bit of trivia. Who knows when the dam was built? No close. 1968. Did you know it’s not a natural dam? Oh, I was a bit disappointed when I found that out. They actually pumped the water in from New Norfolk to fill up this dam, and it’s already treated, so you can drink it. And it’s one of 18 Hobart that supply water to Hobart. So there you go, 1968. So if you’re over 55, it was built after you were born. Does that make you feel old? It makes me feel old.

So this monument, it’s a call and invitation. It says the verse, what shall I render unto God for the Lord for all his benefits? It’s a deep invitation, but it’s a challenging one. If you actually actually stopped and thought about what that means, what shall I render unto the Lord for all his benefits?

The person who preached the sermon was Reverend Richard Johnson. He was the first fleet chaplain. And when you see the monument, you think about what nation around the world has got a monument to a biblical passage that asks this incredible question, let alone to the first biblical passage that was ever preached in that country.

And Uncle Ray [Minnieconn – another Common Grace Aboriginal Sunday author] says it wasn’t directed at Aboriginal people. It was addressed to the convicts, and now it’s addressed to this country, this nation, and these are the beneficiaries of that convict area era.

Have you ever thought about that? This was written in 1788. What shall I render unto the Lord for all of these benefits towards me? That was preached back then. And the benefits towards you are you get to live in this country now. You get to live all the time, all the benefits of all the history, but there’s also the baggage that comes with it. The convicts at the time would’ve been going, “why do I care? The government sent me out of here. I’ve got soldiers, too, all over me. I’ve got judges, too, all over me. I don’t care. There’s no benefit for me being here.”

But the monument still stands, and it’s a question that we need to be addressing. It goes to the heart of the challenges that this country faces with Australia’s First Nations. What shall they render unto the Lord for all the benefits towards him? And you here today are the beneficiaries of that disposition. And so it’s up to you. How do you respond to that question? What shall I render unto the Lord for all the benefits towards him? We have the Nepalese people here who are latecomers in the big scheme of things to this state, and they’re more than welcome here. {Citywide has a Nepalese church campus.]

But they come here because of everything that’s gone before, and they get to live here because of everything that comes before. And if you just recently arrived, you go, “why should I care?” But it’s part of the makeup, and it’s part of that fabric. And it’s a bit like a broken timeline. It’s a broken fabric. It’s a broken plate. It’s just something that’s not quite right.

When you’ve got this timeline that comes along, and you’ve got this glitch in it, and until that glitch is fixed, this country won’t be as free as it can be. This country won’t be as open as it can be. This country won’t be as lucky as it can be until that is fixed.

And it’s a challenging question, how do you fix that? And as we had the referendum last year, and I won’t ask you who voted yes and who voted no, but over 50% voted no. And generally, churches follow public voting. So you’d think there’d be a minimum of 40% of the church that voted no. And yet, and you go, why did you vote No?

I actually think it’s because the Yes story is so simple that it’s hard to believe from my point of view. The Yes question was, do we want to give people a fair go? Do we want to bring people up to be equal with us? That was the question. The no arguments were good arguments, but they were all based upon fear …

And we talk about Uluru Statement from the Heart, this generous invitation, and that’s what the voice was, the voice, treaty and truth. So how do we actually outwork this ministry of reconciliation that God has given us to be in right relationship, to reconcile people to God, to creation to each other? How do we do that?

We do it by trying to turn a page. And this is what Uncle Ray says, and I think this sums up the Statement from the Heart. And this is, I think we’ve been buried so much for 200 years under this whole notion of colonial oppression that it’s almost killed a lot of our dreams off.

And the Statement from the Heart brought those dreams back into some kind of reality for us: voice, treaty and truth. It was a simple question, but it crushed a people when the answer was No.

What shall I render unto the Lord for all of his benefits towards me? Truth, treaty voice. We could have got there as a country, as a country, we had the opportunity, but we refused it. And that is the sadness of it all. Now, if I was given this sermon just after the vote, I would’ve been really narky. So God is good.

But the question I have is, how many extra Aboriginals, because we have a high suicide rate, how many extra Aboriginals killed themselves suicide after the referendum? Because they had this glimmer of hope, the one hope, and it was taken away from ’em. And you actually think about that and it did happen. And you go, that is so sad.

We have our hope in Christ. We have that hope in Christ, which actually helps us get through it. But if you haven’t got that hope in Christ, just so much harder to see through the challenges, like 200 years of oppression; yes, there’s light. Oh no, it’s been taken away again. So Uncle Ray then challenges the churches. Why, theologically, hang on. Why are we not answering the question theologically? Why are we not answering that question? What shall we do for the Lord who benefits us? Why aren’t we answering that question? Why aren’t we doing it for the least of these? Why aren’t we doing it politically as a nation? Why aren’t we doing it as a community? Why aren’t we doing it? And why aren’t we doing it from even a personal point of view?

Watch the full sermon on YouTube