The Anglicans of Armidale elected an evangelical bishop in 1964, a move led by John Chapman, best known as Sydney Anglican’s evangelist. The Professor of History at the University of New England, Thomas Fudge, gave a public lecture on the evangelical takeover of the diocese – making his disapproval plain by wearing a Cope, an ecclesiastical garment disapproved of by many evangelicals.

The talk titled “Secrets of a Church Synod: Conflict, Controversy and Copes in 1960s Armidale” is based on Fudge’s research for a forthcoming history of Armidale Diocese and formed part of the University’s School of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences research seminars.

The Cope belonged to Evan Wetherell, dean of St Peters Cathedral, Armidale 1960-70, on whose diary Fudge based his lecture. Wetherell committed to his journal his severe criticism of the evangelicals and Chapman in particular.

Chapman is the subject of two biographies by Sydney Anglicans, by Michael Orpwood, acknowledged by Fudge, and a more recent one by Baden Stace, both noted in Fudge’s talk, who not inaccurately says Chapman is regarded as a saint in Sydney – although “extremely highly regarded” is how this Sydney evangelical would put it. (Update: there’s also a collection of Anecdotes collected by Dave Mansfield.) He mentored a series of ministers in the Sydney Diocese Department of Evangelism, including Phillip Jensen and Steve Chong. It is a fair assumption that Fudge sees himself as gently evening up the history, using the diaries of an opponent of the evangelical surge in Armidale.

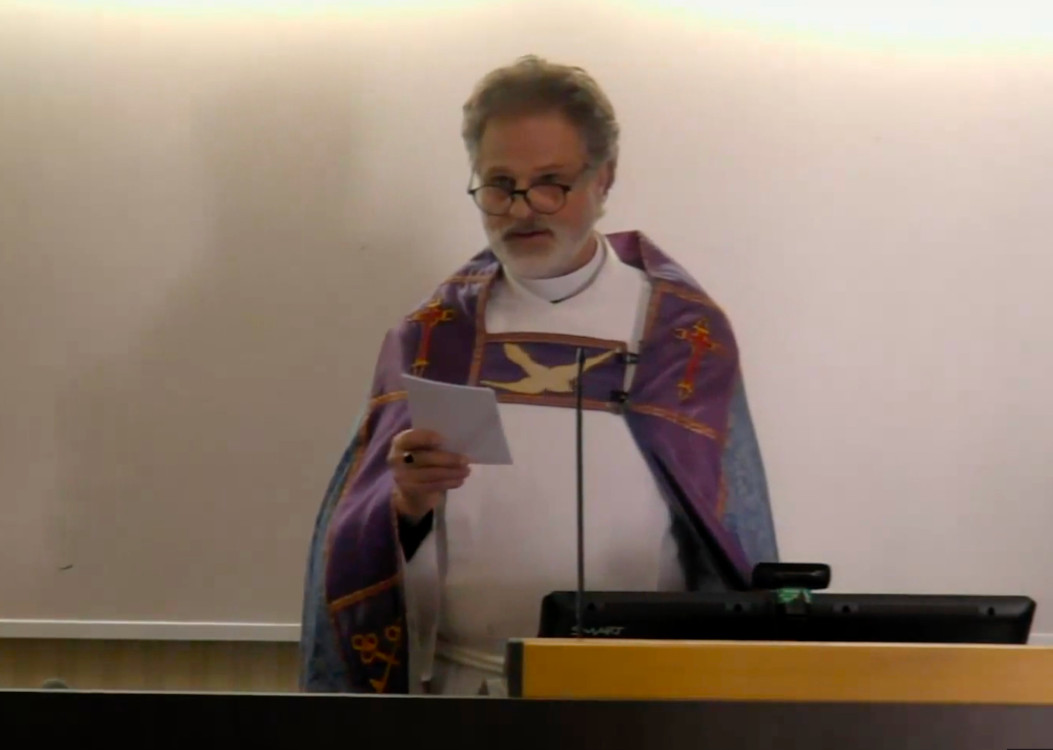

“This is a cope,” Fudge begins, indicating the ornate gown he is wearing (pictured above) “I will tell you about copes and why they’re important when I get to that place in the lecture.” He shows photos of Dean Evan Wetherell wearing the cope and says he is using his diaries for his lectures.

“I’m using these diaries for several reasons. Number one, because they’re really important. Number two is because they have been largely unknown. Thirdly, in consequence, they have been very much underutilised. Fourthly, they have been consulted by no scholar in toto. And fifth, I’m using them not only for these talks, but in the forthcoming book because there’s been efforts to censor them and to prevent consultation.”

Fudge reads from the diaries of a 1963 letter from Canon Robert Kirby to then Bishop of Armidale John Stoward Moyes, “Bishop, I’m gonna try to persuade you of the consequences of your Episcopal decisions and actions. The diocese has changed. There’s deep divisions on fundamental issues in Armadale, and it’s been caused chiefly by arrogant young outsiders who have come into the diocese. And I’ve told you all this before Bishop said, Canon Kirby, we shall see. He predicted a determined and largely successful effort to change the Armidale Diocese. Many people are bewildered and they’re confused by what’s happening the next year.”

That next year, 1964, saw Moyes’ retirement after 35 years and the election of an evangelical Bishop, Clive Kerle, from Sydney.

The 1964 Armidale synod was tough. “I’ve made an effort to speak to every person still living who was in Armidale in 1964 at the Synod. One of the clergy characterised it, and I quote, as ‘a dirty, dirty, misleading, dishonest Synod.’ Oh, surely not. And another member of the House of clergy who went on to be a bishop said the lobbying was, and I quote, ‘ungodly.’ Lay representatives that I have spoken to who attended Synods in the 1960s and seventies were surprised at the quote ‘shenanigans’ at Synod. Some clergy described these synods from the sixties onwards as so full of rivalries and jealousies and tensions you could cut the air with a knife…. and this would increase in the years that followed. I know you’re all shocked. They were not all like this, and truly not all synods and all sessions of Synod were like that. But in 1964, there were a lot of issues at stake.”

The Armidale Express called Clive Kerle the future of the church. And as Fudge disapprovingly points out, that’s what resulted. “The 1964 election Senate in Armadale was a watershed in the history of Anglicanism in this particular province.” A harvest that, as Fudge says, continues to this day.

He describes Rick Lewers, a more recent Bishop, as “implying” in 2014 that the gospel reached Armidale with John Chapman. Fudge’s hurt as someone from a social-justice-focused form of Christianity, with a background in the Episcopal Church of the US, is evident at this point in the lecture. Lewers was unlikely to be saying that there were no Christians in Armidale before John Chapman got there but that Chapman’s work greatly aided the preaching of the gospel in leading the evangelicals who lobbied for Kerle, the evangelical elected in 1964

“Archbishop of Sydney Marcus Loane would later tell John Chapman and I quote, ‘sometimes I wonder if you ever did anything more valuable than pave the way for the election of Clive to Armidale.’ Nobody that I’ve come across speaks badly of John Chapman. Until now: The diaries of Evan Wetherell… present an unflattering but useful insight not available elsewhere. And I quote, ‘Chapman’s name had been given me before I left Brisbane as an example of the complete fanatic, pleasant enough in ordinary matters, but dangerous and perhaps slightly mad on the subject of religion, especially where his tightly held evangelical concepts were concerned.'”

Wetherell goes on to ‘refer to Chapman as ‘the fat man … who laughs a lot, who looks the picture of innocent happiness, but quickly grows apoplectic on certain subjects’. ‘I found Chapman fat. He laughed a great deal, seemed to be ingenious, but before long, I had no doubt about the volcano, like submerged violence of his religious beliefs.’

“Having read those 1,700 pages, I have indeed to assess Evan Wetherell as angry over what he saw as a duplicitous takeover,” Fudge comments. “And he considered this man John Chapman, a stealthy, dangerous character.”

People can get angry in a church battle, especially a decisive one. Wetherell saw Chapman as dangerous precisely because he could see the church structure in Armidale being wrestled away from the social justice-based Christianity of Moyes. The evangelicals would have seen Moyes and his followers as dangerous, too, in playing down the gospel.

“Now, according to Wetherell, Chapman had enormous significance in the theological reconfiguration of Armidale. Wetherell claims Chapman took up the standard to quote, ‘Make this diocese a little Sydney’.”

He succeeded. Fudge recalls Don Beer, a former Associate Professor of History at UNE 25 years ago, labelling, “The stunning Evangelical victory, the elevation of Clive Kerle to the Episcopacy. It’s a major turning point.”

Wetherell is critical of the evangelicals in Sydney diocese and Armidale in voting to follow “the party line.’ “Some people talk solemnly about being guided by the Holy Spirit, but they make sure beforehand that the Holy Spirit has precious little guiding left to do. The party men are carefully instructed how to vote, and as we twice proved in Armidale, they follow instructions to a man.”

And Fudge points to the Stace biography as backing up the view that Chapman led the charge in Armidale. “And Chapman was at the forefront as his latest interpreter phrases. Chapman was, and I quote, ‘party whip and anchorman.’ Chapman was the general organising the troops says another person, a master strategist at work. He was as politically savvy and astute as anybody I’ve ever known.”

My experience in elections in the Sydney Synod is, yes, strong things are said, and advice is given in the form of how-to-votes. At the election of Glenn Davies, “numbers men” on both sides told me they could not be sure of the result. There was a bloc of votes they were uncertain of among the clergy. They voted for Davies. There was electioneering, but it was a real election.

And at the more recent election, that of Kanishka Raffel, there was precious need for how-to-votes. I saw care taken to give proper attention to the other runners.

Fudge is not as fierce as Wetherell in criticising a robust election; it seems to me. His research says there were some more random factors; he calls “flukes” involved in the Armidale election.

One voter from out west was sick of travelling into Armidale and changed his vote to speed things up. Another extra vote affected the election because one minister was ordained early. The Orpwood biography suggests a speech broke a deadlock. Finally, Fudge suggests Peter Chiswell, then a young evangelical voter, was put off by a candidate who took offence at being asked questions by Chiswell, who later became Bishop, and whose son is the current Bishop.

Asked at the end of the lecture if there was any corruption in the process, Fudge says no.

“The high church, Anglo-Catholic coterie were not very smart. They were simply out maneuvered by the strategy of John Chapman and his colleagues. Those guys that whined ‘they did this and they did that’ were simply out manouveured…”

Speaking of strategising and plotting to effect change, Fudge adds, “I agree with Bruce Ballantine Jones [a long term activist in Sydney’s Anglican Church League, which for decades has run voting campaigns in synods] who says, ‘this is just what you do.’ I think they’re right. So I don’t think there’s corruption… There’s no evidence that votes were fraudulent or miscounted. I think the evangelicals won fair and square because they simply out maneuvered and out strategised the other guys.”

Image: UNE’s Professor Thomas Fudge wears the Wetherell Cope while lecturing on John Chapman and the evangelical takeover of the Armidale Diocese

What a great quote ” ‘Chapman’s name had been given me before I left Brisbane as an example of the complete fanatic, pleasant enough in ordinary matters, but dangerous and perhaps slightly mad on the subject of religion, especially where his tightly held evangelical concepts were concerned.’”” With quotes like that why not just publish the diaries.

And what evidence is there to support “And fifth, I’m using them not only for these talks, but in the forthcoming book because there’s been efforts to censor them and to prevent consultation.”

John does Chappo by David Mansfield not count as a third biography which does show up the truth of his laughter? When is the book coming out?

Eddie, thanks for alerting me to The Chappo collection. I will note it in the story. Fudge’s book was announced as “expected in the next few months. It’s apparently been a three-year project.

There is also a paper at MTC which describes the vote electing Kerle as the second election synod as the first was unable to come to a decision after some time and Kerle became Bishop at the subsequent synod so obviously the HS moved numbers in that direction.

And seriously you haven’t read Chappo?

I have read none of the three books!

OK. Then the paper at MTC is a short history. It was a thesis by a student so not long to read. The book coming out next year sounds fascinating

“How to vote” cards at synods…a disgusting invention not isolated to Sydney or Armidale. In my own diocese of Newcastle there were similar documents issued to voters for how to elect members to various positions. I find the practice abhorrent and anathema to the idea of being led by the Spirit of Christ in these matters.

The Holy Spirit can certainly lead through voting cards

The joint reference to Chapman’s size and his sense of humour reminded me of a conversation at a university camp in the 1960s in which he lamented not being able to sunbake on the beach. “People rush up and try to throw me back in,” he said.

Sixty years is a long time! Evan Wetherall’s diaries would be an important source of contemporary thinking. There were differing groupings in the Synod of Armidale (not Senate, not Armadale). Some individuals (at least) met to talk about possibilities, share information and pray extempore. Whilst I do not think there was or could be a disciplined “party line”, I do recall Synod members deploring the apparent block who did not change their votes as different names were put forward. I doubt any clergy member was completely indifferent to the choice. The repeated summonings were tedious, especially for the travellers from the slopes and plains.