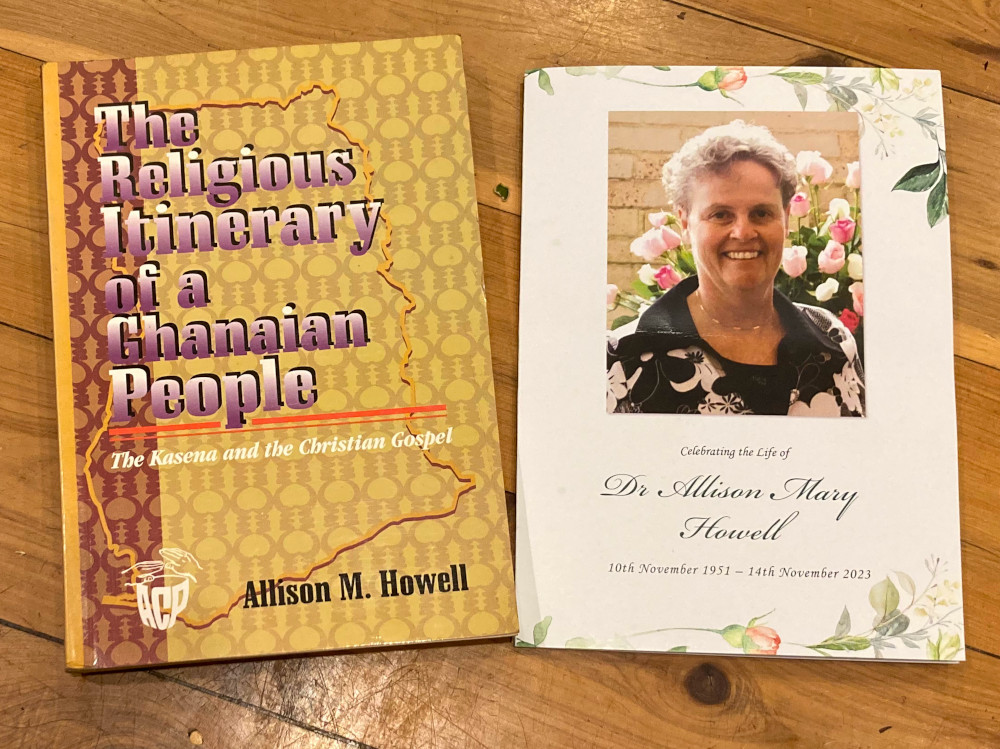

Allison Mary Howell 1951–2023

It took a missionary to teach me that we are all missionaries. In our Western culture, that is more evident than ever year after year, but that insight came to me from Alison Howell decades ago. At my church, St James Croydon in Sydney, we were privileged to have Alison around us whenever she was home from Ghana, where she was both a missionary and a high-flying academic building up the intellectual muscles of a growing church.

For me, Allison was a living example that being faithful does not mean you have to be brain-dead. She served Christ at the highest intellectual level, yet humbly, too. And she’s not the only missionary I know who combines those qualities. Could it be that God sends the best people into the mission field?

I only learned at her farewell this week what an adventurous high flier she was. At first, environmentalism drove her study. She studied the floodplains of the Nepean River as an undergraduate, leading to her lecturing at Sydney University. She widened her studies in environmental geography to A Master’s degree at Toronto University on

The study of water supply in four African countries, Ethiopia, Kenya, Sudan, and Tanzania, took her back to the continent of her birth. As recounted by her brother John, this led to work as a consultant for UNICEF WHO Joint Committee on Healthcare Policy in Water Supply and Sanitation as components of primary healthcare focused on purifying water in those countries. She then worked as a lecturer at the International Training Institute in Sydney for the Department of Foreign Affairs.

How this academic high flier became a missionary was explained by her sister Catherine Brooks, who she had roped into a trip to Sarawak was a field trip for her undergraduate degree – it helped to have an Uncle and Aunt, Hudson and Winsome Southwell, who were founders of the Borneo Evangelical mission.

“Then came the time when Alison told me that she had been contacted twice by the missionary organisation SIM, inviting her to join their team to do research into tribal customs in Ghana, particularly in the north. She informed me that both times, she had refused them, but once again, God, in his love, refused to let Allison keep going her own way. A little later in this conversation, Allison added, ‘If they ask me again a third time, I will know that it’s God who is asking me.’

They asked her again. That was the beginning for Allison giving so many years of her life to working with God in Ghana.”

God’s plan for Allison also involved her brother John, who organised a missions conference while studying at the London School of Theology and introduced mission historian Professor Andrew Walls to a fellow student, Kwame Bediako. Years later, these two men would become Allison’s doctoral supervisors.

The missionary and academic work pattern was woven through Allison’s life.

“Meanwhile, Allison was working in northern Ghana, her first two years of language learning where she became absolutely fluent in [local language] Kasem,” John recounted. Then, over a period of many years, she worked among the people in that region and compiled her knowledge into two books that became indispensable guides to people working in new cultures: a daily guide for culture and language learning and a handbook for encouragers, supervisors and self-directed learners. She researched the impact of the slave trade and wrote the book The Slave Trade and Reconciliation, a Northern Ghanaian Perspective. Her research was extensive and, if documented academically, would provide a very helpful knowledge of the people in Kasena society. So she concluded the best way to do that would be the discipline of a PhD.”

John put Allison in touch with Walls, who accepted her at the University of Edinburgh, and Bediako, who had returned to Ghana to set up the Akrofi-Christaller Institute, which continues to seek to do cutting-edge research that supports the church in Africa, became her associate supervisor.

“Her PhD thesis was published in 1997 under the title, the Religious Itinerary of a Ghanaian People, the Kasena and the Christian Gospel. The publication revealed the study of anthropology and experience among the Kasena people was a foundation for applying her sensitive approach to the nature of the society and its history in its sociopolitical and environmental context. In that same year, Bediako invited Allison to come to ACI as a lecturer.”

From there, she helped foster a new generation of Christian researchers across Africa. God had a plan for Christian scholarship across Africa, and Alison helped the African church mature.

Her’s was a life achievement but also struggle, and she asked that her service of remembrance embrace the themes of hope and suffering.

One story – not told during the service but that has always made me smile – was that alone in Edinburgh, she struck up a friendship with a single mother at a cafe. That woman was struggling to write a book, which later became famous. From St James to Harry Potter, it is only three degrees of separation.

Not only did Allison throw herself into life to serve the Lord, but as her brother David recounts, in her last days, she knew how to die: “Another aspect of her Christian character was her ability to pray for others. She has faithfully prayed for so many of us during her six-week stay in Lifehouse. In June of this year, she would be on all her laptop marking of students’ work. Staff at Lifehouse were taken by this and in how she dealt with them. Staff asked her, “Should we refer to you as doctor or professor?” She said, call me Allison. Her humility and the simple way she lived her life should be an example to all of us. Allison faced the challenges of cancer head-on at all stages. She fought so hard.

“She did stay with the same vigour, strength, willpower, tenacity, and perseverance. She has always displayed. Many would’ve given up. She never did. She remained positive right to the end, and amazingly, I rarely heard her complain about her situation. She maintained a godly dignity and calmness right through to the end. When the Lord finally called her home, we were able to celebrate her 72nd birthday on the 10th of November, the day after she was readmitted to Lifehouse. Upon wishing her a happy birthday, she said, ‘I made it.’ The wonderful caring staff at Lifehouse organised a cake and they all came in singing Happy Birthday. It was a very moving moment. They gave her a knitted blanket as a gift. Allison was beaming from ear to ear by late afternoon and once she had completed talking with all of us, she asked us to leave. Her journey was done.”