Australia and Tanzania, on opposite sides of the Indian Ocean, form a good test case (with a positive result) of whether Christianity is of earthy use. An Anglican Aid seminar asking, “Is education God’s answer to world poverty?” revealed the love and care Australian missionaries gave to establishing an education system for Tanzania; in most of that nation, schools did not exist before the missions came.

“My parents were both teachers, and they worked in a mission station where they taught teachers for lots of little village schools, which were often called bush schools, little village schools, out villages taught by a local teacher who himself had nothing but a primary school himself,” Colin Reed a veteran missionary, told the Anglican Aid meeting casting his mind back to the 1950s. His father then led a teacher training college in Kenya.”

“So that was my background. And then I went to England and trained as a teacher, and that’s my wife went and behold, we ended up doing the same thing. We went to Kenya and taught in a teacher’s college training [students] who had primary school education themselves, no more than primary school education. We also gave them a two-year teacher training course.

Reed describes the interior of Tanzania as too far inland for the first waves of colonialism – the Arabs who ruled Zanzibar and the Portuguese who also traded in slaves on the coast. In the midst of the German invasion, the High Church University Mission and the evangelical Church Missionary Society (CMS) started schools for liberated slave children as the British began suppressing the Arab-led slave trafficking on the east coast of Africa.

“What was the British Navy to do with these African children?” asked Colin Reed. “They handed them over to the CMS, who educated them in India and then sent them back to Mombassa where they set up a centre for liberated slaves…”

Then, a wave of mission schools were set up in the inland. “The pattern there was a central mission station with missionaries and there would be a central school and a teacher training and then that would provide teachers for the Bush school and those Bush schools were also the churches and the teachers were also usually evangelists.”

It was a struggle. East Africa was devastated by World War I. The missionaries were put in prison camps, and the bush schools were kept going by the local teachers. When the British took over Tanganyika with a mandate from the League of Nations, the standards for schools were raised, but the British CMS was finding it costly to run the mission schools. They were thinking of closing the Tanganyika mission.

In 1927, they asked the Australian CMS to take over. “And it was decided that the rector of Dulwich Hill, [George Chambers] who was the founder of Trinity Grammar School and the deputy principal of Moore College, would become the first bishop of Central Tanganyika—and they were the first group of missionaries who went to Tanganyika in 1927.” At that time, the diocese (region) covered most of the inland part of Tanganyika.

That began the strong links between Australian Christians and the children of Tanzania. “

“We respect people like Avis Richardson who taught at Mvumi school for 33 years from 1932 to 1964,” Reed said. He went on to describe how high schools were formed – Alliance schools that included Lutheran and Methodist workers. And finally, after Independence in 1961, the schools were nationalised. “So they just took over all the Anglican church schools, Alliance schools became the high schools. It has to be said that, in fact, the church was quite happy to hand over the schools because a lot of missionary effort and money had gone into running all these networks of schools throughout the country.”

Later, some schools were returned. A burgeoning population meant that the government welcomed support from the churches once again.

“Around 26% of [primary school age] children were not in school in 1970, .. by 2019 this decrease[d] to about 13%, which is great, a reduction of 50% in 50 years. That’s pretty good.” Cameron Jansen, Anglican Aid’s projects team leader, gave the good and bad news about global education, using UN and World Bank stats.

“This reduction has occurred at the same time that the school age population has increased by 60%. So even though there are 730 million more school-aged children in the world today than in 1970, there are actually 61 million less kids out of school than back then. I think that’s pretty amazing. That’s an awesome achievement.”

But Jansen dug deeper. He told us the main improvements occurred between 1995 and 2010, particularly bringing the inclusion rate for girls to match boys. But more recently, Covid and the outcome of the wars in Afghanistan will have affected more recent stats.

“But how many kids are actually completing school?” he asked. “To know this, we look at something called the completion rate, which refers to the proportion of students in a cohort who complete a given level of education…

“In 2021, the global ultimate completion rate was 92% for primary, 81% for a lot of secondaries and 62% for upper secondary, which looks pretty good on the face of it.” But when he showed the rates for the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Burundi, Indonesia, Pakistan, and South Sudan, which are nations Anglican Aid is focused on, the picture was bleaker.

“Most countries have improved their completion rate with the exception of South Sudan. Burundi for example, saw a massive improvement from 13% in 2000 all the way up to 53% by 2015. But you can see even by 2015 except for Indonesia, 20 to 50% of students were still not completing primary school.”

Bishop Mwita Akiri from the Diocese of Tarime in the far north of Tanzania gave the conference a very practical example of what education can mean for Tanzanians, and how the Gospel drives out fear. “People really are subjected to poverty from disease for example because they simply don’t relate the water they’re drinking and the disease going to get later. But if you educate people well enough, then surely disease will decrease. Particularly for those who will know that if I drink or if I take water from the well or from the strip, I can boil it and it’ll be safe for me.

“Now, surely, children who come to school, if a school is a good school, they will learn about disease, they’ll learn about contaminated water, they’ll then be more cautious in their families…”

“I know that there are some educated people in Tanzania who will still perhaps go to witch doctors when they get ill, but that’s not because they don’t have knowledge or education. That is simply because the world review in Africa is very supernatural, but those who are educated when they get ill, they’re likely to go to the hospital because they know this is a disease I’ve got from water or from something else. But those who are less educated are likely to believe that the disease is caused by a misfortune.

“They go to the witch doctor. They go to a fortune teller. So in fact they simply cannot relate contaminated water and the illness, they think this is a misfortune and then that is where the gospel comes in because we have to preach the gospel to our people to know that they they’re safe in the hands of Jesus Christ.”

The responsibilities that face Australians as Christians in a wealthy country was made clear in the Anglican Aid conference, with a focus on education.

But what of the questions raised at the beginning of the conference? We were asked, “Is education God’s answer to world poverty?” In something of a spoiler, perhaps, Mark Thompson, the Principal of Moore College, laid out the long history of Christian passion for education.

From the beginning, literacy has been valued so that the Scriptures may be read, from the early church through the communities of Monks to the Cathedral Schools established by Charlemagne throughout his empire and run by the masterful Alcuin of York. Several of those schools became the first Universities in places like Paris, Bologna, and Oxford. In the 19th century, there was an explosion of mission schools with 2 million attendees by 1915.

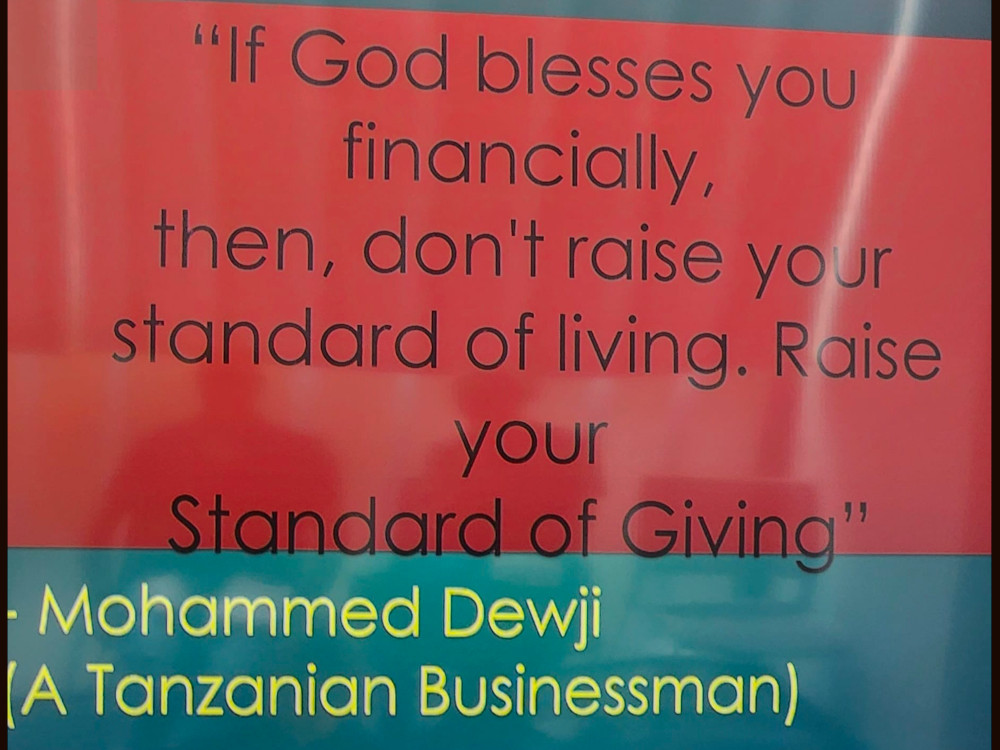

“Perhaps the only thing I agree with Mohammed it that we are people of the book,” said Thompson referencing the origin of that saying, but drawing attention to the fact that Jewish and Islamic faiths and others have promoted education. In humility we recognise education is not a purely or primarily Christian activity.

Thompson pushed us to look behind the history, to our ultimate motivation, the gospel. The ultimate answer to “Is education God’s answer to world poverty?” is that education is not the Gospel. But history shows, both globally and in Tanzania especially, it has been a flavoursome fruit of the Gospel.

Update Moore College is diving into the topic of the bonds of love between Australia and Tanzania https://moore.edu.au/events/tanzania/

Main image: A slide from Bishop Akiri Mwata’s talk at the conference. Image Credit: Eddie Ozols

Great summary John.