Merri Creek Anglican’s Peter Carolane on The quiet revolution that transformed Melbourne Anglicanism

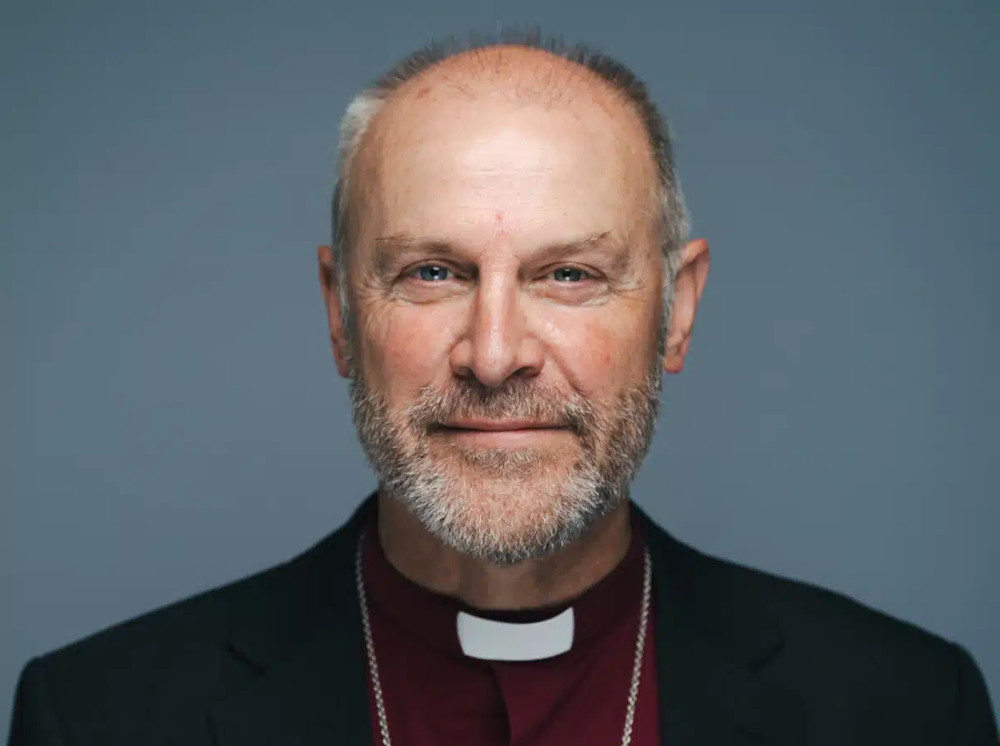

Something extraordinary happened over the weekend at the Anglican Diocese of Melbourne’s Archbishop’s election synod. When the votes were counted and Bishop Ric Thorpe (Pictured) from London’s Diocese of Islington emerged as our next Archbishop, it wasn’t just an election—it was the culmination of a quiet revolution that has been reshaping the church landscape of our city for almost two decades. Ric’s role has been to lead the Diocese of London’s church planting and church growth work. A church planter as an Archbishop! How did that happen?

For context, we need to rewind the clock to the early 2000s to understand why Ric’s appointment feels so significant. Back then, church planting was the domain of the outliers, the dreamers on the margins who dared to imagine new ways of doing ancient faith. Some viewed church planters with suspicion, and others saw them as threats to tradition. The phrase “church planter” conjured images of young, bearded hipsters drinking pretentious coffee—and, let’s be honest, there might have been some truth to that stereotype.

But revolutions rarely announce themselves with fanfare. They begin in whispers, in small gatherings, in the bold prayers of people who refuse to accept the status quo. What started as a handful of fresh expressions and missional communities slowly, persistently, began to take root across Melbourne’s diverse suburbs and communities.

The transformation didn’t happen overnight. It required patience, courage, and the kind of stubborn hope that characterises all meaningful change. One by one, pioneers stepped forward. They got ordained, tried new things, failed, and tried again. Many of their plants flourished beyond anyone’s wildest expectations. What was once dismissed as fringe experimentation gradually revealed itself as genuine renewal.

What we witnessed follows a pattern that social movement theorists like Bill Moyer have mapped with striking precision. Moyer’s “Eight Stages of a Movement” provides a lens through which we can understand how the church planting revolution evolved from:

(Stage 1) Normal times

(Stage 2) Prove failure of institutions: as traditional parish models experienced rapid decline, struggling to engage younger and more diverse populations.

(Stage 3) Ripening conditions: The early church planters created new models and organised alternative networks while facing resistance from established structures.

(Stage 4) Social movement take-off occurred as more planters emerged and gained visibility.

(Stage 5) Perception of failure occurred when some plants didn’t survive

(Stage 6) Majority public opinion arrived as the broader diocese began to recognise that church planting wasn’t just trendy experimentation but an essential mission strategy.

(Stage 7) Success is Ric’s election: when what began as alternative practice has become institutional policy.

There is a Kingdom beauty about what has happened. In the speeches about Ric on Saturday, we witnessed that the stereotype of the young white male church planter has given way to a far richer reality. Chinese-speaking congregations have been rapidly planted and replanted. Sudanese communities have joined in. Persian and Arabic-speaking new plants are one of our diocese’s strongest growth edges, each a testament to the Gospel’s power to transcend cultural boundaries. The revolution has become genuinely multicultural, reflecting the magnificent diversity of Melbourne itself.

It was also very clear on Saturday that a new generation of young female clergy is stepping boldly into leadership roles in church planting and renewal. They have brought fresh perspectives, deep theological insight, and an infectious passion for mission that has energised the entire movement. So many of their speeches articulated the enthusiasm for change.

Having been closely involved in diocesan church planting discussions for about 20 years, I thought I understood the scope of this transformation. But even I was caught off guard by what happened at the synod. When the moment came to choose our next Archbishop, something remarkable occurred: a movement that had grown quietly in the shadows suddenly spoke with one unified voice. The church planters, the renewalists, and the communities scattered across suburbs and cultures came together to support a leader who embodied their vision for the future.

Yet we’d be naive to think this was simply a grassroots uprising that happened by chance. Like all significant institutional changes, Ric’s election involved multiple factors—some visible, others operating quietly behind the scenes. Every power structure has its ‘back room’ people, and the Anglican Diocese of Melbourne is no exception. There were undoubtedly conversations in corridors, strategic phone calls, and careful coalition-building that helped crystallise support around Ric’s candidacy. Influential voices within the diocese likely recognised that the church planting movement had reached a tipping point and threw their weight behind a candidate who could harness that energy.

This doesn’t diminish the movement’s authenticity or the genuine enthusiasm for Ric’s leadership. Rather, it acknowledges the reality of how institutional change actually happens—through a combination of grassroots passion and strategic influence, organic growth, and deliberate orchestration. The most effective revolutions are often those that manage to marry popular momentum with institutional savvy.

Ric Thorpe’s election wasn’t just about choosing a capable administrator or a gifted preacher, though he is certainly both. It was about recognising that the church’s future in Melbourne lies not in maintaining what has always been, but in courageously planting what could be. It was about acknowledging that the margins had become the centre, that the experiment had become the mainstream.

This appointment represents a profound shift in understanding mission and ministry in the 21st century. It signals that the Anglican Diocese of Melbourne is ready to embrace a future where new communities of faith can emerge organically, where cultural diversity is not just tolerated but celebrated, where innovation is not feared but fostered.

Amid all the celebration and hope, we must remember something crucial: Bishop Ric is not the Messiah. He is a gifted, dedicated human being who will inevitably make mistakes, face setbacks, and encounter challenges that would test any leader. The revolution that brought him to this position was built by the prayers, sacrifices, and collective vision of countless ordinary people doing extraordinary things by the power of the Holy Spirit. It will be sustained in the same way.

This is why our work is just beginning. Ric will need our prayers—not the polite, perfunctory kind we offer out of duty, but the deep, sustained intercession that acknowledges the spiritual magnitude of the task ahead. He will need our active support and willingness to join him in the messy, exhilarating work of planting churches, building communities, and proclaiming hope in a city that desperately needs it.

The quiet revolution that elected Ric Thorpe as Archbishop reminds us that God often works through movements we barely notice until they’ve transformed everything around us. Twenty years ago, few could have imagined that the church planters on the fringe would one day help choose the leader of one of Australia’s most significant dioceses. But here we are, witnesses to the power of patient, persistent faithfulness—and living proof that even ecclesial institutions can experience the kind of movement dynamics that reshape societies.

Understanding this as a movement helps us appreciate how far we’ve come and what lies ahead. Movements don’t end with institutional success; they either evolve into new cycles of renewal or risk calcifying into the very structures they once challenged. This brings us to Moyer’s eighth stage of social movements:

(Stage 8) Continuing the struggle

The question now is not why we elected Ric, but what we will do with the opportunity his leadership represents. The revolution that brought him to this moment was never about one person—it was about a vision of the church that is bold enough to plant new communities, diverse enough to embrace all cultures, and hopeful enough to believe that the best days of the Gospel in Melbourne are still ahead of us.

The margins have spoken. Now it’s time to see what grows from the centre.

First published at www.merricreek.org used with permission.

London

CNN

—

Opposite a bed in central London, light filters through a stained-glass window depicting, in fragments of copper and blue, Jesus Christ.

[url=https://bsp2tor.com]блекспрут[/url]

Three people have lived in the deserted cathedral in the past two years, with each occupant — an electrician, a sound engineer and a journalist — paying a monthly fee to live in the priest’s quarters.

[url=https://blacksprut2rprrt3aoigwh7zftiprzqyqynzz2eiimmwmykw7wkpyad.net]блэкспрут сайт[/url]

The cathedral is managed by Live-in Guardians, a company finding occupants for disused properties, including schools, libraries and pubs, across Britain. The residents — so-called property guardians — pay a fixed monthly “license fee,” which is usually much lower than the typical rent in the same area.

[url=https://bs-2best-at.ru]bsme .at[/url]

Applications to become guardians are going “through the roof,” with more people in their late thirties and forties signing on than in the past, said Arthur Duke, the founder and managing director of Live-in Guardians.

[url=https://bsmeat.ru]bsme at[/url]

“That’s been brought about by the cost-of-living crisis,” he said. “People are looking for cheaper ways to live.”

bsme .at

https://m-bs2bestat.ru