History has a way of rhyming, if not repeating, and John Dickson’s book Bullies and Saints: An Honest Look at the Good and Evil of Christian History gives this reader an introduction to patterns of Christian blundering. But as often happens, history – and Dickson is a historian – helps us see the present. Working out how Christian thinking is different from worldly thinking has never been as easy as many of us imagine. Dickson’s book is a chronicle of how we too often pattern ourselves after the world and become bullies. (But he includes saints, too – as per the title.)

Here’s how one passage in Bullies and Saints helps us understand Christians’ position in Western societies.

“The words ‘image of God’ refer, in part, to humanity’s authority to have domination over creation,” Dickson writes. “This neatly fits with evidence from the ancient Near East that monarchs were sometimes thought to be a living ‘image’ of divinity. The difference in Genesis is that the concept is democratised. It emphatically refers to all men and women. The former Chief Rabbi of Britain, the much-celebrated intellectual Lord Professor Rabbi Jonathan Sacks (what a title!), wrote in his 2020 book Morality, ‘That is what makes the first chapter of Genesis revolutionary in its statement that every human being, regardless class, colour, culture or creed, is in the image and likeness of God himself…’

Referencing Genesis 5:1-3 where Adam has a son “in his likeness, according to his image,” Dickson continues: “The parallelism is unmistakable. Just as Adam had a child in his likeness and image, so every man and woman bear God’s image, so every man and woman bear god’s image. To be made in the imago dei is to be regarded by the creator as offspring … and therefore own kin.

“As ‘theological’ as this may sound, it has immediate social implications. it means that I am to treat other human beings as having infinite dignity as offspring of the creator.”

Can I suggest that realising this principle lies behind many of the struggles Christians have fitting into the present present Western society? It explains why many Christians have difficulty slotting into left or right, conservative or progressive political positions. Some will happily position themselves comfortably on either pole, but others of us cannot sit comfortably – we squirm. But please don’t blame Dickson for what follows.

Take two of the causes that Christians will be defined by in the public imagination – abortion and same-sex marriage. A vast majority of Christians oppose abortion on the grounds of imago dei and the further testimony of the scriptures. Yet, this has been used to weaponise their votes, particularly in the US. A decades-long political campaign of “responsible conservatism” has wedded many conservative Christians to other politically conservative groups with agendas of small government, lower taxes, and gun rights (in the US).

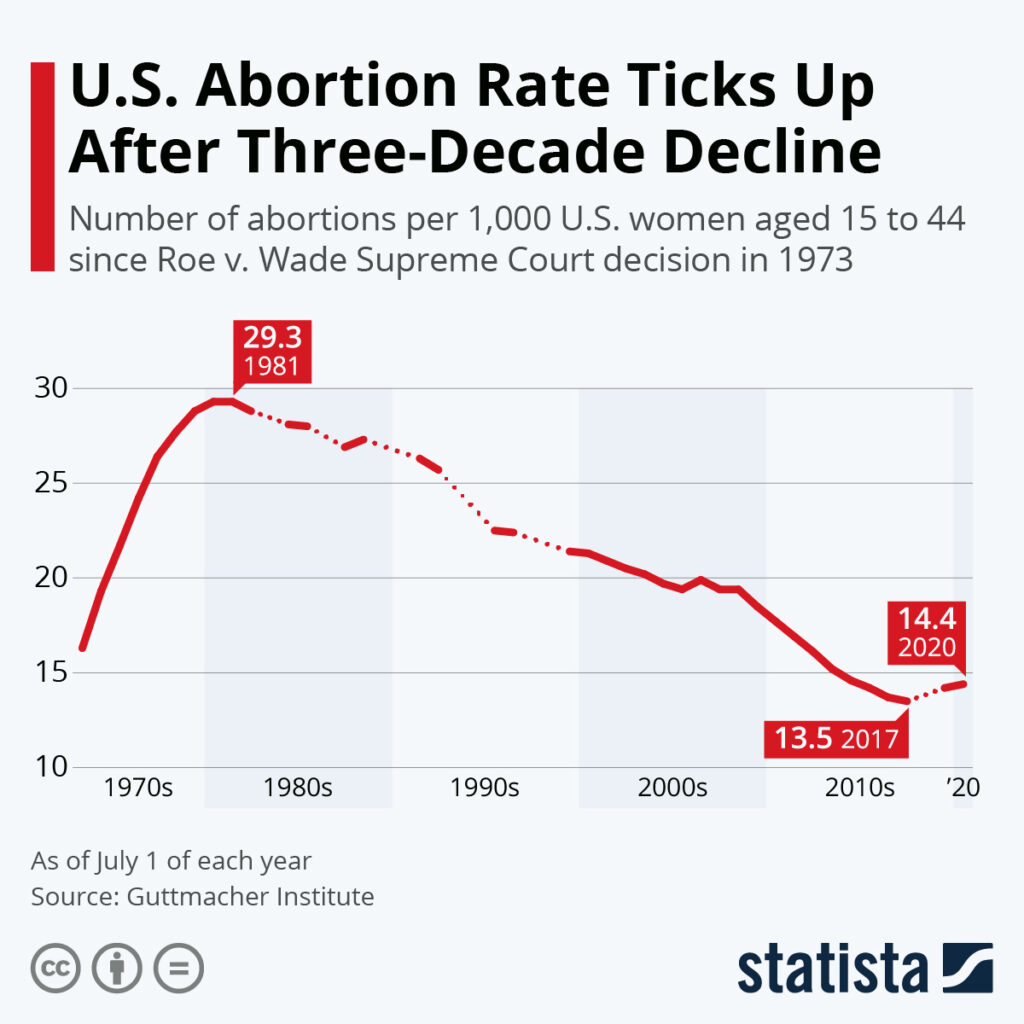

This social and political coalition is just like any other: it has fissures and is unstable. Consider the fact that before the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization US Supreme Court decision that overturned Roe v Wade, abortion had been declining steadily. Welfare spending, looking after single mothers, appears to have reduced abortions during the Democrat administration. Is a low tax ideal, withdrawing or lowering welfare payments conducive to less abortion? And did the Trump era put an end to the downward slide of abortions?

Post Dobbs, beyond that graph, in 2022, there are slightly more abortions overall in the US, reversing the downward trend, but there also are more live births in states with abortion bans.

Given that when an abortion question appears on a state proposition ballot (US-speak for a referendum), abortion wins even in “red” states like Ohio or Kentucky, a different way to change people’s view on abortion other than legislation is needed. A state (and churches) generous to those with unwanted pregnancies would be a good start. It’s summed up in the slogan, “Love them both.” Why? Because both the unborn and their parent are made in the imago dei.

On the other hot topic of Christian response to LGBTQIA persons, there is a similar challenge of responding with care and and respect even while pushing against society’s direction.

In both questions, the desire for equality arguably planted by Christianity into Western culture is behind the call for dignity for women (my body, my choice) and the call for equality in marriage laws.

There is a real need for Christians to respect these calls for dignity while maintaining our convictions. So, supporting welfare programs and equal pay to avoid a pregnancy poverty trap or opposing draconian laws against LGBTQIA persons seem logical outcomes of Genesis 1.

We don’t fit. Sometimes we are “righter than the right and lefter than the left”, possibly a slogan for The Other Cheek. Christianity is not positioned to be a comfortable place for conservatives to simply crique those to the left of them, or for lefty Christians to take shots at the right.

Long after abortion ceases to be a convenient political peg to gather voters around, Christians will maintain their conviction that the unborn are made in the imago dei (righter than the right) and will seek the welfare of those who face poverty raising a child (lefter than the left). Small government is not suitable for them.

And on LGBTQIA, the vast majority of Christian schools (should be all) will make all kinds of children welcome. Consistent with teaching Christianity, most will have some LGBTQIA staff. Right and left at the same time. That balance will be the subject of a significant debate as the Albanese government moves to enact a religious discrimination bill this year. An indication of how schools respond is given in an SMH report of submissions to a NSW inquiry.

Sumissions show varying responses to balancing the imago dei and the rights of schools to teach christianity.

For example a submission from the Presbyterian church of NSW observes “From Christian convictions we are committed to treating all people as equally valuable and deserving of dignity and respect.” But with respect to schools argues “Many Christians schools are attractive to families because they operate with a consistent Christian ethos and express a Christian world and life view in all aspects of school life. This cannot be maintained if schools can only prefer candidates with Christian convictions for a limited range of positions. For example, there are proposals that schools should only be granted exceptions from the Act in relation to senior leadership roles, chaplains and Christian studies teachers. However, this would not enable schools to maintain their total Christian ethos. The current Act allows schools in NSW that are established for a religious purpose to employ Christian staff who support their ethos. It also allows schools to expect students to behave in consistency with Christian ethical standards including Christian sexual ethics. Any changes to the Act should continue to enable schools to do this.”

It is not clear in this submission whether students could manifest an LGBTQIA identity at the school. On the other hand, the sumission makes a strong case arguing for schools to prefer to employ Christians in more than a very limited range of positions, which appears fundamental to having Christian schools. The delicate balancing between religious freedom and the imago dei is apparent here.

(The Other cheek will report other sbmissions in a future story.)

But Australian evangelicals also face the task of talking carefully to their African friends about draconian laws that put LGBTQIA people in prison. That’s hard to do within the Anglican evangelical world but necessary.

None of this arguementt is meant to suggest an abondonment of christian view, but rathet explores how to manifest them with respect. (1 Peter generally but 3:15 especially).

Perhaps more deeply, as pastor David Rietveld discusses in his Being Christian After Christendom, the cultural yearnings for equality and dignity represented in movements we might want to question are gospel openings. As he acknowledges, he draws on the work of Chris Watkin, author of another recent and significant book, Biblical Critical Theory: How the Bible’s Unfolding Story Makes Sense of Modern Life and Culture. Watkin explains how, through Christ, the cultural yearning of Jews and Greeks are met.

Our task is to show how the cultural yearnings of our age, particularly the desire for equality are best met in Christ.