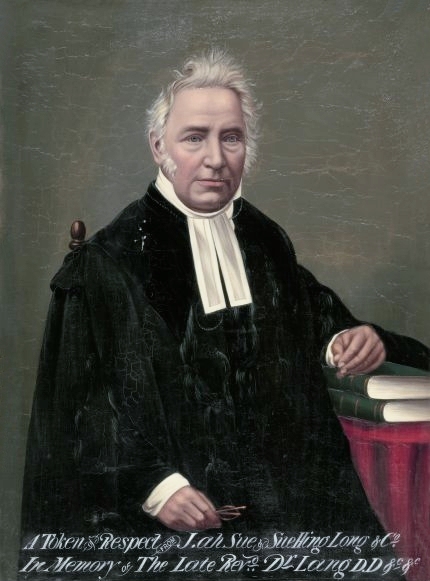

An excerpt from John Dunmore Lang’s Sermon National sins, the cause and precursors of national judgments Preached in Scots church Sydney in 1838. Lang is often regarded as the father of the Presbyterian Church in Australia. It stands with Baptist John Saunders’ sermon “Claims of the Aboriginies,” preached in the same year as early Christian acknowledgement of injustice against First Nation’s people. It is in effect, an Acknowledgement of Country in sermon form. Would it be welcome in today’s Presbyterian churches?

Lang rests his sermon on the character of God, who cares for the world.

The fact that the world is governed by an infinitely wise, and powerful, holy, and beneficent God has been a ground of joy and rejoicing to all good men in all past ages. “The Lord reigneth,” saith the Psalmist; “Let the earth rejoice, and the multitude of isles be glad thereof.”

Oh, my brethren, if the world were governed even by the wisest and best of mortals, how miserably would it be governed for myriads and myriads more of its inhabitants! How much iniquity would then pass unseen and unpunished! How much injustice and oppression and cruelty would be perpetrated with impunity! Virtue might be struggling with adverse circumstances in ten thousand instances and in ten thousand places simultaneously, but there would be no eye to behold it, no pen to record it! And the prayer of the destitute, which the Lord God Almighty delights to hear and to answer graciously from the place of his holy habitation, would never reach the ear of his vice-gerent upon earth! Vice-gerant is Lang’s reference to governments as God’s instruments, as suggested in Romans 13.

Lang then argues that just as God acted in Israel’s history to promote justice and righteousness, similar princples apply to other nations.

Although the ancient Jews, in whose whole history as a nation, … were, in their

national capacity, God’s peculiar people, and were placed under a very peculiar dispensation, I think it quite evident, from the whole tenor of the Old Testament Scriptures, that the principles of the Divine Government that were acted on in regard to that ancient people were also designed to be acted on in regard to every other nation or community enjoying similar privileges and placed in similar circumstances, in comparison with other nations or communities, to the end of the world.

For as the temporal and political prosperity of the ancient Jewish people was always conjoined with their national maintenance of the worship of the one living and true God and with their general practice of that pure morality in which he delights, while their national apostasy from that worship was uniformly visited with general judgments and national calamities, we find from the experience of all ages that it is “righteousness that exalteth a nation,” and that sin is not only, “a reproach,” but a source of general calamity, and wide-spreading disaster, and final ruin to any people.

Lang then reveals Isael’s principal national sin.

I observe … in the first place, that the public or national sin which more especially provoked the divine anger, and called down divine judgments on the ancient Jewish people, was the sin of blood-guiltiness.

You will find a most remarkable proof of this in [2 Samuel 21:1] where it is recorded that there was a famine in the days of David three years, year after year, and David, rightly conceiving that there must be some national sin unrepented of and unforgiven, that God meant to punish in that national judgment, enquired of the Lord.

And the Lord answered, ‘It is for Saul, and for his bloody house because he slew the Gibeonites.’

But who and what were those Gibeonites, you will probably ask, on whose account the whole nation of Israel was thus visited with so grievous a famine during the reign of David, that man after God’s own heart? Why we are told in the 2nd verse of the same chapter: ‘The Gibeonites were not of the children of Israel, but of the remnant of the Amorites, and the children of Israel had sworn unto them, and Saul sought to slay them in his zeal to the children of Israel and Judah.?

Lang describes the Gibeonites, who had received a promise of protection from Israel’s earlier leader Joshua for protection, as “a miserable tribe of the ancient Aboriginal inhabitants of the land of Israel.”

Despite getting that protection by false pretences, God had bought punishment on Isreal after Saul slughtered the Gibeonites for breaking Joshua’s promise. then applies it to the colony of New South wales

Therefore, when, after the lapse of three centur.es and upwards, Saul, as king of Israel, sought to slay the Gibeonites in his pretended zeal for God and for the nation, the Lord brought a famine of three years duration upon the land for this national crime, during the reign of his successor David.

Now, my brethren, let us ask ourselves seriously and in earnest and standing, as we are in the immediate presence of God on this day of fasting and humiliation on account of our social and public, as well as of our private and individual sins; let us ask ourselves seriously and in earnest, whether, as the European colonists of this territory, we can lay our hands upon our hearts and plead not guilty concerning the Gibeomtes, I mean the wretched Aboriginal inhabitants of this land.

Alas! we are verily guilty concerning these, our brethren; not only have we despoiled them of their land and given them in exchange European vice and European disease in every foul and fatal form, but the blood of hundreds, nay of thousands of their number, who have fallen from time to time in their native forests, when waging unequal warfare with their civilized aggressors, still stains the hands of many of the inhabitants of the land.

Lang proclaims a collective guilt on the colonists.

And think you, my brethren, that if God visited the slaughter of the Gibeonites, which had been perpetrated by the bloody bouse of Saul alone, on the whole nation of Israel, with three successive years of famine, the blood of these innocents will call to heaven for vengeance in vain against this whole Emo- pean community?

Assuredly not; if it is the same Almighty God who still sitteth in the heavens and reigns supremely among the inhabitants of the earth!

…

Yes, brethren, every district of this land of our adoption has been defiled with the blood of these innocents; and who knows, but it is for this that the Lord has been pleased, a second time, to call for a drought upon the land, and upon the mountains, and upon the corn, and upon the new wine, and upon the oil, and upon that which the ground bringeth forth, and upon men, and upon cattle, and upon all the labour of the hands?

If so, we have reason this day to humble ourselves mightily before the Lord, our maker, as the sinful members of a sinful community, taking with us these words of the prophet: O Lord, though our iniquities testify against us, do thou it for thy name’s sake; for our backslidings are many; we have sinned against thee? [Jeremiah 14:7]

.

Lang deals with one of the key objections to focusing on the needs of dispossessed First Nations peoples.

Some of you will doubtless tell me, in reference to the preceding enumeration of our public or national sins that having had little or no intercourse with the Aborigines yourselves, you cannot possibly have contracted guilt in the manner alleged; that being for the most part inhabitants of towns…

Recollect, however, that when God visited the whole nation of Israel with a famine of three years? duration for the slaughter of the Gibeonites, it was the bloody house of Saul alone that was really guilty; the sin of that bloody house being regarded as a national sin and punished accordingly by Almighty God.

Lang concludes by asserting the duty of Christians to speak against evil and use whatever influence they have to oppose it.