Most Christians are more concerned with heaven and the narrow path to get there, but what of the broad path that Jesus told us leads to destruction? (Matthew 7:13-14 KJV) What “destruction” means is at the centre of what the editor of the book, Four Views on Hell, Preston Sprinkle, assures us is a “rapidly growing debate about the nature of hell [1]. This new book on hell is one of evangelical Publisher Zondervan’s “Counterpoints” series in which four of five eminent Christian writers share dissenting views.

Zondervan produced a newer version (2016) of this title because “The annihilation view of hell has grown in popularity among evangelicals,” according to Sprinkle “Many theologians, pastors, and Christian laypeople today are leaning toward or embracing an annihilation view of hell.” [2] A minority of evangelicals, such as UK Anglican leader John Stott have held that view in the past. “Annihilation” battles it out with the traditionalist view of eternal torment in this book.

In this story, The Other Cheek will look at the first two essays – the traditional view and one called “conditional immortality,” sometimes called “annihilationism.” (The other two essays reflect views that include some type of purgatory or afterlife sanctification for either believers or non-believers.)

As Southern Baptist theologian Denny Burk begins his defence of hell as eternal torment, he asks key questions “The question of eternal conscious torment really does come down to who God is. Is God the kind of God for whom this kind of punishment for sin would be necessary? Or is he not? What does the Bible say about God and the judgments that issue forth from him?” [4] Burk is Denny Burk, Professor of Biblical Studies at Boyce College, the undergraduate school of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, and is president of the conservative complementarian flagship the CMBW – the Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood

He urges readers not to let a visceral or emotional view of hell to determine their belief. What we believe about hell, he says, tells us a lot about what we believe about God.

He lists Isaiah 66:22 – 24; Daniel 12:2 – 3; Matthew 18:6 – 9; 25:31 – 46; Mark 9:42 – 48; 2 Thessalonians 1:6 – 10; Jude 7, 13; Revelation 14:9 – 11; 20:10, 14 – 15.8 as the ten key passages requiring a belief in a hell of eternal concious torment.

The Matthew passage contains Jesus’ words about hell, with Burk arguing the Old Testament images of Hell are being taken up in the New Testament as Jesus speaks. “

“The term rendered as “hell” or transliterated as Gehenna (v. 9) is the Greek term geenna, which derives from the Hebrew gê hinnōm, which means ‘Valley of Hinnom,'” Burk writes. “As mentioned [in his description of Isaiah] this valley was the site of child sacrifices to the idol Molech during the era of the kings (2 Kings 16:3; 21:6). The practice so provoked the Lord to anger that Jeremiah prophesied God would destroy these idolaters in the Valley of Hinnom and would leave their corpses to rot. There would be so many corpses that there would be no room to bury them all and that the valley would be renamed “Valley of Slaughter” (Jer. 7:31 – 34 NIV). This valley’s association with fire and judgment is the background for its use in intertestamental literature and for its appropriation in the New Testament, where it became an image for the place of final judgment.26 These verses indicate that hell is but one of two possible destinies in the afterlife. The other alternative is for people to “enter life” (vv. 8 – 9). Every other instance of “life” in Matthew refers to eschatological life or “eternal” life (Matt. 7:14; 19:16, 17, 29; 25:46), and that is how it is used here. It is the “life” of the age to come.27 There are only two destinies. Those who are disciples enter into eternal “life,” and those who are not disciples enter into ‘the eternal fire’ or the ‘fiery hell’.”

Burk argues that the descriptions ‘the eternal fire’ or the ‘fiery hell’ are set in parallel, which renders hell as an everlasting reality. That, he argues because the word translated ‘”‘eternal’ (aiônios) means “time without end” in Matthew, although it means “a long time” elsewhere.

Another Matthew passage, the separation of the sheep and goats in Matthew 25 when Jesus returns to Judge the world, is cited by Burk.

Those on Jesus’ right are “blessed of [the] Father” and will “inherit the kingdom prepared for [them] from the foundation of the world” (v. 34). Those on his left are “accursed” and are heading to “eternal fire” (v. 41). The first act of the final judgment will be a separation. And in that moment, the horrifying realization will begin to descend on the goats. They will know that it is the last time they will ever see the sheep again, and they will know that what is about to happen to them will be irrevocable. [6]

Of the passages used to argue the traditional case, those from Revelation might be the hardest for advocates of annihilation to argue against. The worshippers of the beast are described in chapter 12 as “tormented with fire and brimstone” in chapter 14. “John says that the pain and distress do not end but go on everlastingly,” Burk writes ” “If the language was not clear up to this point, John clarifies the endless duration of their experience: “they have no rest day and night” (Revelation 14:11).[7]

“Despite Burk’s claim to be rigorously biblical, I submit that his argument is essentially deductive: Since God is infinitely great, any sin against such a God deserves infinite punishment, [8]” John G Stackhouse.

The meat of the annihilationist argument is that the traditional view of hell makes additions to the text of the Bible. “In passage after passage of Burk’s analysis, moreover, he adds meanings that are not in the text — especially the idea that the suffering depicted therein is eternal, which is, after all, begging the question,” Stackhouse writes. ” “Isaiah 66, to begin with, speaks of worms and fire that do not die, but they are consuming corpses, not zombies or some other form of perpetually living “undead.” The deathlessness of the symbols of judgment, worms and fire speak of the perpetuity of God’s holy antipathy toward sin, but the corpses themselves are dead. They’re finished. And Burk has the integrity in this case to admit that he is, indeed, adding information to the text: ‘Though not mentioned specifically in this text,this scene seems to assume that God’s enemies have been given a body fit for an unending punishment.’”’ I suggest that it is not “the text” that is doing the assuming here.”

The Stackhouse argument is that while the fire might be everlasting, the suffering of the people cast on it is not. “In his third passage, Matthew 18, Burk again confuses the fire (which is a figure of God’s eternal repugnance and resistance toward evil) and the experience a (mortal) being might have of that fire of judgment: ‘eternal fire … expresses the pain that must be endured by those in hell.’ In fact Burk rightly quotes the gospel passage as speaking of ‘perishing’ and ‘complete destruction,’ phrases that really don’t sound like ‘staying alive in a conscious state forever.'”

Responding to the most difficult passages for the annihilationist position -Revelation 14, Stackhouse points to Revelation 20: “As the account continues in the book of Revelation, we read, ‘Then Death and Hades were thrown into the lake of fire. This is the second death, the lake of fire; and anyone whose name was not found written in the book of life was thrown into the lake of fire (20:14 – 15). The similar language would lead the conscientious reader to a similar conclusion: Death and Hades are destroyed (cf. 1 Cor. 15:24 – 26), and ‘anyone whose name was not found written in the book of life’ is similarly destroyed, dead, gone — not immediately, as we shall see, but eventually. Being thrown into a lake of fire surely incurs pain, and that suffering might last a while, depending on what or who is being judged. The beast and the false prophet are contained therein for a millennium: (Rev. 19:20). But it is impossible to imagine “Death and Hades” suffering. The “second death” means, ultimately, to disappear.

“Yet what about Revelation 20:10? “And the devil who had deceived them was thrown into the lake of fire and sulphur, where the beast and the false prophet were, and they will be tormented day and night forever and ever.” Surely this passage teaches eternal torment for the wicked? This passage is not as obvious in its meaning, however, as it might first seem. Later in the same passage, as we have just noted, we find “Death and Hades” thrown into the same lake of fire (v. 14). And the next verse sees “anyone whose name was not found written in the book of life” thrown into the lake of fire. So does that mean that lost humans will be “tormented day and night forever and ever,” as traditional teaching says?”

Stackhouse’s argument is that given that we have death and Hades thrown into the lake of fire, the passage makes the most sense if they are to disappear. And the humans, consigned to the same place, will disappear, too. His argument does not deny God’s wrath but that it is temporary.

“I respectfully suggest that the view of God as keeping human beings conscious in torment forever does nothing to achieve God’s other purposes of saving the creatures he loves and enhancing shalom. I suggest further that such a view doesn’t even achieve its desired result: to enhance God’s glory. Quite the contrary: It poses an unbiblical and therefore, unnecessary stumbling block to genuine faith. Such a view is, to speak more bluntly, sadistic, and the God of the Bible, the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, is the exact opposite of one who gets joy from the suffering of others: he gets joy from suffering for others (Heb. 12:2 again). Praise this God, then, “For his anger is but for a moment; his favour is for a lifetime. Weeping may linger for the night, but joy comes with the morning” (Ps. 30:5 NRSV).[12]

[1] Zonderva,. Four Views on Hell (Counterpoints: Bible and Theology) (p. 9). Zondervan Academic. Kindle Edition.

[2] p 9

[3] p 10

[4] pp. 21-22.

[5] pp. 28-29

[6] p 31

[7] p 43

[8] p 55

[9] p 58

[10] p 59

[11] p 91

[12] p 59

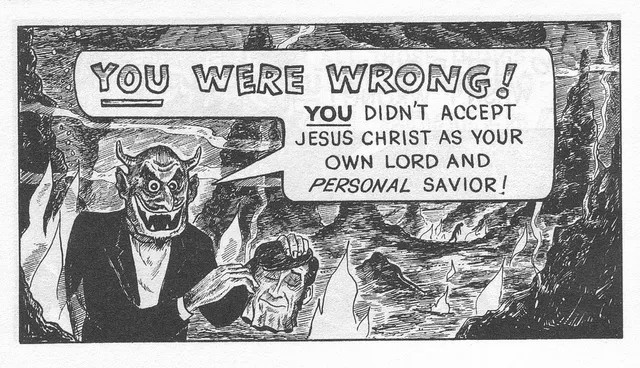

Image: Hell as depicted in a Chick tract.