Russell Moore, the former Southern Baptist heavyweight, now editor-in-chief of Christianity Today, told National Public Radio (similar to ABC Radio National) that evangelicalism needs to be rescued. He commented to NPR’s Scott Detrow, host of All Things Considered why he thinks US Christianity is in crisis.

“Well, it was the result of having multiple pastors tell me essentially the same story about quoting the Sermon on the Mount parenthetically in their preaching – turn the other cheek – to have someone come up after and to say, where did you get those liberal talking points? And what was alarming to me is that in most of these scenarios, when the pastor would say, I’m literally quoting Jesus Christ, the response would not be, I apologize. The response would be, yes, but that doesn’t work anymore. That’s weak. And when we get to the point where the teachings of Jesus himself are seen as subversive to us, then we’re in a crisis.”

DETROW: “I mean, how do you even begin to fix that problem, though, when the central message of the gospel is something that a lot of people in the church do not seem to want to fully embrace?”

MOORE: “I don’t think we fix it by fighting a war for the soul of evangelicalism. I really don’t think we can fix it at the movement level. And that’s one of the reasons why, when I’m talking to Christians who are concerned about this, my counsel is always small and local. I think we have to do something different and show a different way. And I see in history every time that something renewing and reviving has happened, it’s happened that way. It’s happened at a small level with people simply refusing to go with the stream of the church culture at the time. And I think that’s where we need to be now.”

In referencing people who think turning the other cheek is too weak, Moore is referencing “Christian Nationalism,” an emerging movement that has swallowed a portion of US evangelicalism. Aussie blogger Stephen McAlpine has been examining a book that defines the movement, Stephen Wolfe’s The Case for Christian Nationalism. McAlpine writes, “What piqued my interest in the book was a rather bitter encounter on social media with a couple of Australian pastors who took a long-term, well-regarded and godly older evangelical leader to task for a blog post he had written for The Gospel Coalition Australia, which encouraged churches to make their websites accessible in terms of language and approach to non-Christians.

“The pushback was excoriating. Excoriating and scornful. Scornful of that leader who has done much for the cause of evangelicalism and sound biblical preaching in this country. And when I checked, it was from young, rather earnest looking Christian pastors in confessional churches on the east coast of Australia. Pastors of churches that run a tight evangelical ship, if you know what I mean. Tight and Right. Oh, and nary a Christian tattoo or a pair of jeans to be seen. It’s implacably cigars and sartorial elegance all the way down.”

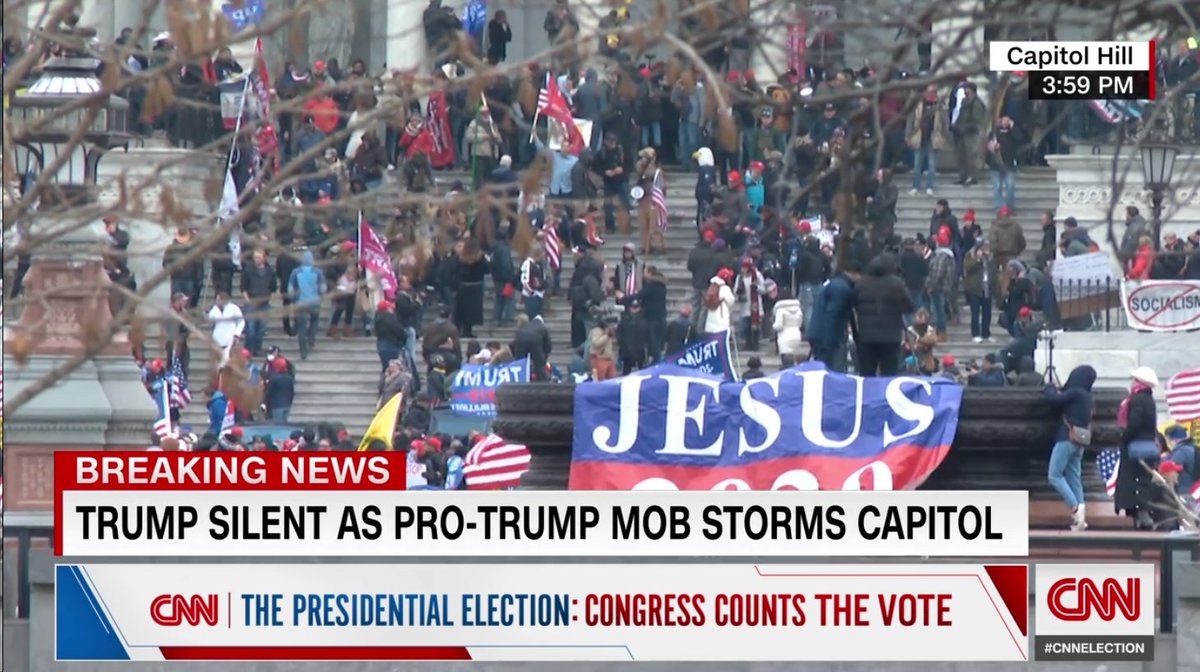

Asked to define Christian Nationalism for a Council on Foreign Relations webinar, Andrew L. Whitehead author of co-author of Taking Back America for God: Christian Nationalism in the United States, pointed to the images of Christian symbols like “Jesus Saves 2020” or praying around a cross or a flag, “Jesus is My Saviour: Trump is My President,” in the January 6 invasion of the US Capitol Building. In words, Whitehead defines Christian Nationalism as “a collection of myths and traditions, symbols, narratives, and value systems that idealize and advocate for a fusion between Christianity, and you can place an asterisk by Christianity, with American civic life. So the reason we placed an asterisk there is—I’ll show a bit today and as we talked about in our book—is that it includes assumptions of nativism, white supremacy, patriarchy, authoritarianism, militarism, and it sanctifies and justifies violence in the service of what they deem the greater good or even God’s plan.”

McAlpine sees racism in the movement. “It’s the casual racism and self interest that takes my breath away. I don’t know what Wolfe’s favourite colour is, but it reads like his shirts are brown, especially in his demand for exclusive Lebensraum for particular ethnic Christianity. And for all of its theological profundity in the opening chapters – Wolfe is an wide reader and interacts extensively within the Reformed tradition – there’s a crassness, and quite frankly unbiblical and anti-gospel flavour to those statements.”

Moore described what he sees as hyped-up fear of an “existential threat” driving both politics and the reactions of Christians. “I think that the roots of the political problem really come down to disconnection, loneliness, sense of alienation. Even in churches that are still healthy and functioning, regular churchgoing is not what it was a generation ago, in which the entire structure of the week was defined by the community. And I think there’s a great deal of fear that comes from that. And then when you look around at legitimate concerns, often, that Christians have about the society around them, but when that’s packaged in terms of existential threat – which I don’t think is unique to the church right now – I think that that almost every sector of American life is seeing this with what Amanda Ripley calls conflict entrepreneurs, people who are willing to come in and say, everything is about to be lost, and desperate times call for desperate measures.”

From Melbourne, the theologically conservative blogger Murray Campbell also argues that evangelicals need to watch how they respond when society moves against traditional belief. “I understand why Christians across the United States are concerned and even angry at … some of [the] values and views that have captured hearts. I appreciate why Aussie believers are troubled by various moral agendas that have been normalised in our political and educational institutions. However, frustration and concern with politicians and the political process, [are] not a reason for reactionary theology and poor exegesis.”

Moore has been critical of Donald Trump and, in an editorial, attacked Tucker Carlson when he was still on Fox News for supporting “replacement theory,” which is the idea that elites in the U.S. are diluting the political power of White Americans by encouraging non-Whites in other countries to immigrate to the country. His support for strong action against sexual abuse in Southern Baptist churches led to his move from a top denominational job to join Christianity Today.

“Every blood-and-soil form of fear-based identity politics thrives on defining us in terms of visceral categories like race, tribe, or nationality. This assumes a blatantly social Darwinian view of what human communities are or can be,” Moore wrote. “The problem for Christians is that the gospel contradicts this ideology at its very root.

“If ‘Christianity’ for you is white and American, then it is not only out of step with the Bible; it is also precisely the kind of religion that almost every chapter of the New Testament explicitly repudiates as carnal and pagan.

Donald Trump is no fan:

Later on CNN’s “Anderson Cooper 360,” Moore told Cooper, “We sing worse things about ourselves in our hymns on Sunday mornings.” Citing lyrics from the hymn “Amazing Grace,” he added, “We are a wretch and in need of God’s grace.”

Grace, not the seizure of state power, is Russell Moore’s message.

WEll done. Thanks for these insights into what is a travesty of belief for followers of Jesus Christ. Thanks that you continue to bring news in the Christian world, rather than vanilla-ise your news.