Digging into the terrible history of the Newcastle Anglican Diocese, author Anne Manne has done a service in balancing the record of denominational involvement in the sexual abuse of children. In her new book Crimes of the Cross: The Anglican Paedophile Network of Newcastle, Its Protectors and the Man Who Fought for Justice, Manne chronicles some of the worst crimes against children and arguably the most efficient cover-up. She makes it clear that child abuse was never a “Catholic problem” in the sense the worst abuses occurred exclusively in the Catholic church. But it is a “catholic” issue in that it has been widespread throughout the church.

Manne’s book starts with the happy childhood of Steve “Smiley” Smith from the working-class suburb of Edgeworth. This happy childhood on the bushy edge of the then-industrial city revolved around the Anglican church. Steve’s mother, Margery, was the church organist, and she and her four boys cleaned the local church weekly. Steve’s father, a sheet metal worker for BHP, was a churchwarden. Besides church, another family ritual was handing out Labor how-to-votes at election time.

Father George Parker arrives as parish priest just as Steve is turning ten. The long-haired priest, a talented musician, wins the parish over, especially the women. He grooms the Smith family, getting close to Margery, although several Smith males dislike him. But Steve is his target, and Parker’s training of him to be an altar boy is his opportunity.

Parker has four churches in which to hold services, and he took Steve with him. The abuse started at the little church in Minmi, a coal mining settlement. Steve was trapped. He was no longer “Smiley.”

As the abuse escalated, Steve discovered during visits to the nearby St Albans boys home that other priests like Peter Rushton, another local priest, were abusing boys. But Steve felt he could not tell; it would have shattered his mother’s world. When another altar boy victim told their family what Parker was doing to them, the congregation ran them out of the church. Steve could see that Priests were held in such high regard that anyone complaining would be run out of town.

But when, at 14, Steve told his mother, she believed him. By then, he had been raped hundreds of times. But after her tragic death, Steve discovers that she had been to see the Bishop, Ian Shevill, an encounter from which she had emerged hysterical.

Struggling with depression, anxiety and panic attacks, Steve makes two attempts to tell the Anglican church of his abuse – first to Assistant Bishop Richard Appleby and later, encouraged by the news that a local Catholic priest has been convicted of child abuse, he rings an Anglican hotline, where his call is answered by the dean of the Cathedral, Graeme Lawrence.

From here, Manne’s account widens. Lawrence was at the centre of what Manne describes as a “grey network” of pedophiles. Pedophile priests were moved on to another diocese without discipline, a move known as “throwing a dead cat over the fence.” Parker had been sent to Victoria. Manne unravels the story of how when Parker was put on trial, “team church” kept church documents from the prosecution, and mysteriously, documents were altered. Stymied by the church, Steve’s case is “no billed.”

By grim coincidence, Dean Lawrence, who was sentenced to a maximum of eight years in jail for the sexual abuse of a 15-year-old boy at the Cathedral, was released from prison this week.

But there are heroes in Manne’s book, even an Anglican one. The Hollingworth scandal, which resulted in the former Archbishop of Brisbane standing down as Governor General due to his poor handling of sex abuse cases, in Manne’s words, “sent shivers down the spines of Newcastle Anglicans.”

The Hollingworth scandal caused the national Anglican church to act. A new National Professional Standards Ordinance (church law) called for professional independent investigations independent of the bishop.

Manne writes that it broke the conspiracy of silence on child sexual abuse and spelled the end of Newcastle’s “team church”.

In Newcastle, the Anglican scandal could finally emerge from behind the Catholic scandal, which had been brilliantly reported by Joanne McCarthy of The Newcastle Herald. A new Anglican bishop, Brian Farran, recalled to Manne that he thought no one in Newcastle realised the implications of the new professional standards regime. Joined by a new registrar (business manager), John Cleary, the bishop pushed back against “team church.”

In an interview with Phillip Adams on Radio National, Manne credits Garth Blake SC, the Sydney Anglican barrister who was the architect of the professional standards revolution in the Anglican Church.

Steve Smith and other victims were able to come forward and receive compensation.

Another hero for Steve was ex-policeman Michael Elliott, who was appointed as the Professional Standards Director of the Newcastle Diocese. He unravelled the forgery of a critical church document that had led to Steve Smith’s case against George Parker being no billed. Elliott became Steve Smith’s first ally within the Newcastle church structure.

As Elliott investigated the diocese, The list of perpetrators and evidence of abusers in positions of power kept growing, Manne reports.

Manne takes the description of a fake celibacy among Catholic priests that saw sex with women as forbidden but sex with men and boys as somthing priests are entitled to from Professor Patrick Parkinson’s work and attributes it to the powerful Anglo-Catholic faction in Newcastle Anglicanism. Dean Graeme Lawrence and Archdeacon Peter Rushton were the most powerful clergy in the diocese, members of the extreme Newcastle Anglo-Catholic faction and pedophiles – although Rushton escaped conviction.

The Newcastle Diocese was split. “Team Church” fought the defrocking of Graeme Lawrence all the way to the NW Supreme Court. They lost, and Lawrence was defrocked. Manne’s account lays bare the infighting and the strong support of influential Novocastrians for Lawrence, a superb networker.

After the court battle, the vengeful Lawrence supporters gutted the Newcastle Professional Standards Ordinance, but their victory was shortlived.

In 2013, Greg Thompson, a former Newcastle boy who had become bishop of the Northern Territory, became the Bishop of Newcastle. But he, in Manne’s words, was “psychologically prepared” to take on “team church.” He had been abused as a teenager by senior Newcastle clergy. He knew their mindset and, together with the police, took them on. Bit by bit, he dismantled the network of important Newcastle identities that had defended Lawrence.

In the last chapters of Crimes of the Cross, the downfall of “team church” at the Royal Commission into the Institutional Response to Child sexual abuse is replayed by Manne. She tells how, after devastating testimony at the Commission, the entire Cathedral Council, a redoubt of the “team Church”, is finally sacked by Thompson.

During the Royal Commission, which was sitting in Newcastle, Manne wandered up the hill to the imposing Cathedral that still dominates the skyline of Newcastle. “The sun was dipping now, flashes of light alternating with dusk, buildings starkly illuminated or disappearing into shadow. Suddenly, there was a burst of brilliant sunlight, and I saw high on the hill above me the spires of the Anglican Cathedral lit up by the last rays of afternoon sun. Towering above every building below, its imposing bulk dwarfed everything else.

“I walked up to the Cathedral. It is open to anyone. That afternoon, there was a solitary worshipper and me. Outside, a sign advertised concerts of choral music. Inside, the building was grand in the extreme, thick stone pillars down each side, huge, beautiful stained-glass windows, and an ornately carved wooden pulpit. I could imagine the tall figure of Dean Graeme Lawrence sweeping along in his white lace and gold brocade robes, and how, amid this grandeur, a congregation might feel close to God.

“How elevated an ordinary worshipper might feel by associating with high-ranking clergy, becoming a leading member of the laity, and acting as a protector. A humdrum life escaped, the mark of distinction upon them.

“The power and the glory.

“Then I got it. So much of this terrible story was about status and the pursuit of social significance.”

Correction”,: The sentence about the Royal Commission has been amended to make it clear the downfall described was that of “team church”

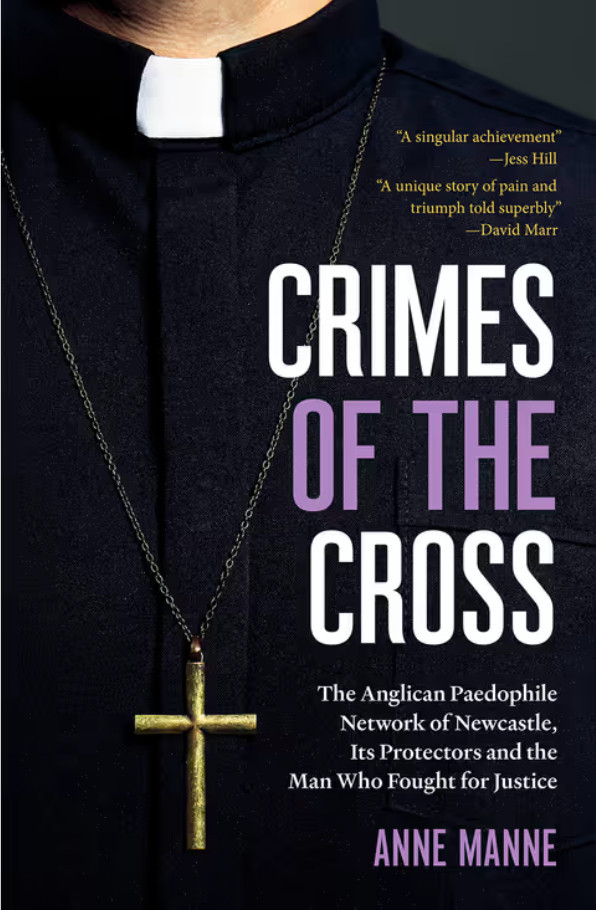

Crimes of the Cross: The Anglican Paedophile Network of Newcastle, Its Protectors and the Man Who Fought for Justice

Anne Manne, Black Inc Books, 2024

$29.75 Available from Booktopia

Image: Newcastle Cathedral Image Credit: denisbin/flickr

And what exactly does this mean? You have: the downfall of the Royal Commission into the Institutional Response to Child sexual abuse is replayed by Manne. Really? Is this the sneaky hand of AI at work? I have dipped a little into the very voluminous records of the Commission in relation to Newcastle and Grafton. Such shameful reading. If there is a downfall, may it be of perpetrators and their ignorant supporters.

Manne’s book is a brilliant retelling of Steve Smith’s story. Its very well written and researched. Read it before you jump to concusions, please.

Another reader points out where I slipped up. It should (and will) read the downfall of team church at the RC….