When classical composer Nigel Westlake and his librettist, indie musician Lior, invited Lou Bennett to collaborate with them in a celebration of the life of aboriginal activist Uncle William Cooper, they were simply seeking a Yorta Yorta musician. They did not realise they had approached a direct descendant of Cooper’s family to join them.

“Uncle William Cooper was my Grannie Ada’s brother,” writes Bennett, a composer/songwriter in her own right, and a Yorta Yorta/Dja Dja Wurrung woman. “Their mother, my Nanny Kitty, has been found in numerous historical documents sharing our language. Now as her great, great, great granddaughter it is with great honour I share some Yorta Yorta with you.

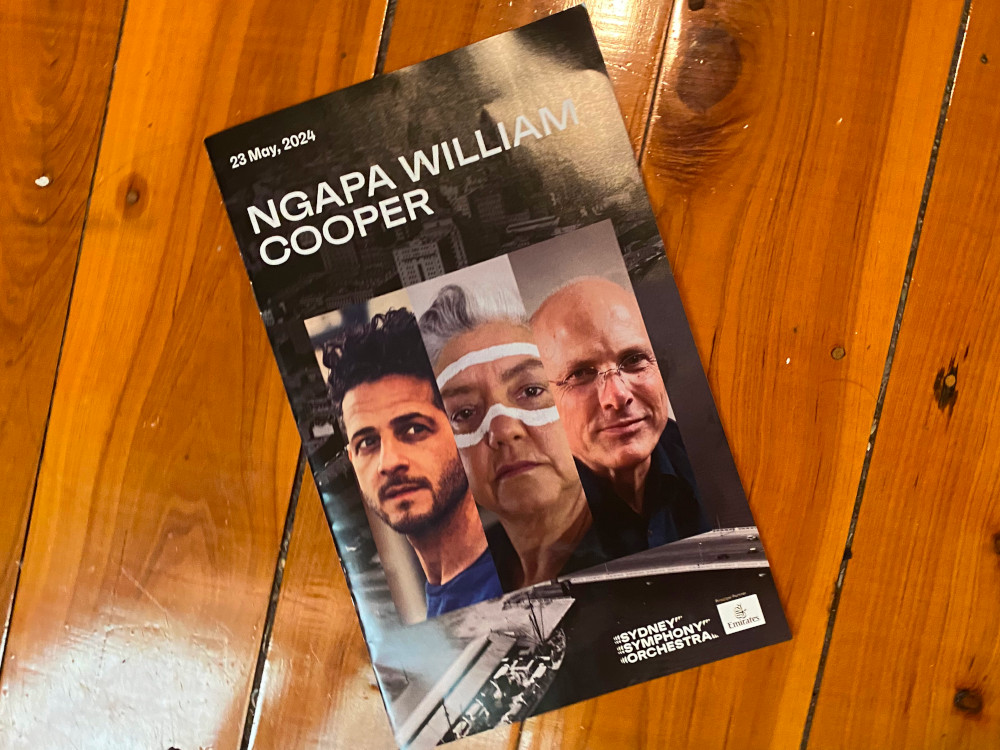

An expanded chamber setting of Ngapa William Cooper had its world premiere at the Sydney Recital Hall last night. Westlake conducted the piece, and Lior and Bennett sang with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra. In an after-concert discussion, Westlake revealed that Bennett adds more Yorta Yorta each time the piece is performed as the living language continues to revive.

The piece reveals that Australia has heroes and artists who create music about them. Ngapa William Cooper focuses on Uncle William Cooper leading a protest by the Australian Aborigine’s League following Kristallnacht. “We are a very small minority, and we are a poor people, but in extending our sympathy to the Jewish people, we assure them of our support in every way.”

The piece opens with Lior singing in Hebrew and Bennett responding in Yorta Yorta, reflecting their backgrounds.

In Footscray in Western Melbourne, Cooper reads of Kristallnacht:

“And I read

The night of broken glass

Bodies crouched in terror

Streets of blood and crystal shards

And I read

Skulls smashed

Synagogues burned to the ground

They said flames were still shooting into the sky at dawn“

Ngapa William Cooper has a subtitle, A Story of Compassion.

At the end of the Earth, a downtrodden and despised minority had large enough hearts to protest injustice done to another minority under attack.

“I traded places

With a young man bleeding

On the Street of broken glass

“And though he was half a world away

I could see him in my reflection

clear as day

and I knew I was a ghost if I let him fade away

This piece of reflection causes us to reflect.

Asked what William Cooper would write about today, Lou Bennett gave a brave answer, “the genocide.”

For an evangelical Christian, the piece poses a further challenge because Uncle William Cooper’s Christianity has been swept away.

In a profile of Cooper by Matt Busby Andrews. published at Eternity and The Other Cheek, the stories are woven together:

“William Cooper identified strongly with the Jews. When he was born in 1860, whitefellas had all but taken their land of milk and honey – the fertile country along the Murray River north of Echuca. The new white masters could be cruel as Egyptian slave-drivers – they denied Aboriginal pastoral workers their wage, and stories were told of landed men going on “blackhunts” after church picnics of a Sunday.

“Amid this violence around the river, William Cooper found one place where he knew he was safe. It was on an old sacred site called Maloga. His sister had taken him there when he was 14, and he’d met a towering white man with a long black beard called Daniel Matthews. Here he learnt to read and write – and the great stories from the black book from an ancient people who had become slaves and whom God, the Creator of the world, would rescue. All it took was a leader brave enough to confront Pharaoh and say, let my people go.

“Following a church service in January, 1884, Cooper approached Daniel Matthews and said “I must give my heart to God….” He was the last of his brothers and sisters to become a Christian. But from there, he began a lifelong work to speak for “the least of these”, to confront governments when they were unjust, and to demand to be heard at the highest levels, from the Premier, to the Prime Minister to the King.”

One reaction a Christian might feel to Ngapa William Cooper is to feel rejected or “othered.” This feeling is real, and has to be processed carefully,

William Cooper’s life, as told in Ngapa William Cooper, provides one way forward. His heart was big enough to hear another’s story despite experiencing personal and communal oppression. If our faith is real, it will be seen not merely in pursuing our rights and telling the truth but in living to uplift the needs of others.

Then maybe, our story will begin to creep in, to how others tell Australia’s story.

Very good article. May I share this on my Facebook page?

Sure!

Thank you for bringing this to our attention. The YouTube video is very moving; it must be a transforming live experience! Highly recommend Bain Atwood’s biography of William Cooper; it was a revelation for me.